Recovered WWII rifle prompts Binghamton University alum to research, tell D-Day soldier’s story

Binghamton grad Jim Farrell writes "Uncle Matty Comes Home"

Martin Teahan’s Facebook page has received more than 88,000 “likes” since it was created in March 2016. Not bad for a soldier who was captured and killed in Normandy, a casualty of D-Day.

For more than seven decades, Pvt. Teahan had been both man and myth to his family — revered for his bravery as a paratrooper and beloved by nieces and nephews who had never met him but who knew all the stories about their fun-loving “Uncle Matty.”

“I went to Catholic School, and the nuns said you had to pray for someone who died in your family. I was maybe 6 years old, and he was the only one I knew of, so I’ve said a prayer for him the rest of my life,” says nephew Jim Farrell ’83, who was born 12 years after the death of his uncle.

Uncle Matty might have remained famous only among his family but for an astonishing email sent in spring 2016. Seventy-two years after Uncle Matty’s death, an M-1 rifle with “M. Teahan” carved into it had been found in France and, thanks to online records, traced back to his family.

“Maybe 10 years after D-Day you saw these kinds of things,” Farrell says, “but to come up with one now is highly unusual, especially to be able to trace it back to the soldier.

“The first thing that came to my mind was, ‘We’ve got to get this home.’”

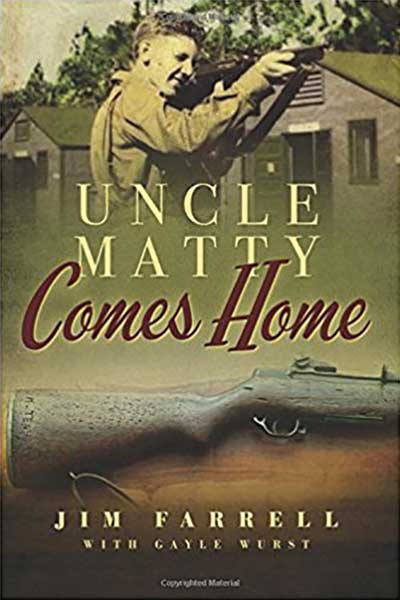

Over the next year, Farrell immersed himself in Uncle Matty’s life and death, taking a deep dive into WWII history, meeting men who served with Teahan and writing a book called Uncle Matty Comes Home, which he published in October 2017. Since then, Uncle Matty’s popularity has soared on social media and among military brass and WWII vets. A museum exhibit is next.

Does all history matter?

The proliferation of searchable databases means it’s never been easier to look into the past and make connections with the present. Family trees, oral histories, self-published memoirs: What does all this personal history mean for professionals who study history?

The answer is a bit complicated, say two Binghamton University historians.

“I love history, and I want people to be excited about it. For many people, it’s family stories that connect them to the past in ways that other people’s stories don’t,” says Associate Professor Stephen Ortiz.

But the work done by professional historians and what people are interested in have few points of intersection, he says. “Often, [historians’] interests are not driven by family or personal matters, they are driven by bigger questions about large processes or large social or political issues that we want to know more about.”

It wasn’t always that way. For example, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, a great deal of history was published for popular consumption, including book-of-the-month club titles.

But through the latter part of the 20th century, professional historians worked to raise the level of scholarship in their field, demanding more rigorous research and analysis.

Nonacademic publishers now rarely print histories written by academic historians for large public audiences.

“The rise of the academic press changed things,” Ortiz says.

Today, credentials, peer review and publication are essential for building a career in academics. That’s good, Ortiz says, but some historians, early in their careers — especially before tenure — are forced to restrain some of the curiosity that drove them to study history in the first place while they build their reputations.

“It’s about answering big questions as the profession sees it and not as everyday people see it,” Ortiz says. “This new atmosphere of Ancestry.com and family genealogies and books like [Uncle Matty Comes Home] shows that there is a real yearning for historical work; it’s just not a yearning for the historical work of an academic historian.”

Genealogists do the digging

Associate Professor Diane Miller Sommerville’s forthcoming book, Aberration of Mind: Suicide and Suffering in the Civil War Era South, uses suicide as a measure of the emotional and psychological costs of war.

“Without understanding the full extent of the damage it caused to the psychological well-being of soldiers and civilians, it is impossible to know the cost of the war,” she says.

To identify people who had committed suicide or been deemed suicidal, she turned to the genealogy website Ancestry.com for source material.

Social historians like her owe a lot to genealogists because they are the ones doing the digging, she says.

Even so, information about suicide or suicidal behavior is typically buried in records and often unrecognized by the person building the family tree. Once Sommerville identified a potential source worth pursuing, she contacted the genealogist, often a family member, to seek more information.

“They love to share. I think that’s the best of both possible worlds, where we share our own specialties and what we’ve found in our own research.

“I couldn’t have written my book without it,” Sommerville says.

Verify, verify

Ortiz and Sommerville urge genealogists and armchair historians to develop two skills: Verify facts whenever possible and give your subject context.

If you are doing scientific research and you find a fact repeated over and over again, it’s tempting to think it must be correct, Sommerville says. But with family trees, which are generated by genealogists on Ancestry.com, much of the information is “lifted” and utilized by other people on their own trees without verification. It’s easy, therefore, for mistakes to be repeated over and over. The best thing to do is work your way back to the original source material for verification, with the knowledge that even that might have a name misspelled or a date transposed — or worse. You could have the wrong person.

A pitfall for armchair historians is not knowing the historical context of their subjects. “Nonhistorians struggle to ground their work contextually. What you often get are colorful, descriptive pieces of writing that aren’t very helpful in describing why things happened,” Ortiz says.

Yet, professional historians shouldn’t dismiss every nonscholarly work, he says. There are stories that maybe haven’t been told yet.

“Sometimes we don’t think to ask certain questions, and so we don’t really know that part of the story. That’s what a good lay historian leads us to; they’re the ones who sometimes ask different kinds of questions and look at things a bit differently,” he says.

Uncle Matty brings history home

Farrell is not a professional historian — he is a partner in a digital market ing agency. But he spent about 16 months gathering facts and putting Uncle Matty’s story into context, with the help of editor and writer Gayle Wurst, who has worked with authors and veterans on more than 80 WWII projects.

“It drove me to try and get a clear picture and get as much accurate information about him and what he was like and what happened in the invasion of Normandy. It was a passion — or obsession is probably a better word,” Farrell says.

Before his popular social media presence, Uncle Matty could be found on a website for the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, attached to the 82nd Airborne Division.

French Army Gen. Patrick Collet used that resource to identify “M. Teahan” and track down Teahan’s family.

“The rifle was found close to where Matty died,” Farrell says. “It was kept in a French farmer’s family for 50 to 60 years. The family sold the rifle to a collector, and the French [general] saw it and took it off the collector’s market and donated it to us. He wouldn’t take a penny.”

Teahan is buried in the American Cemetery in Normandy. His rifle hangs in a glass case in the office of the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Gen. Mark A. Milley, and will be donated to the new National Museum of the United States Army in Fort Belvoir, Va., when it opens in 2019.