Binghamton University researchers are killing cancer cells

Binghamton scientists use dual thermal ablation to tackle pancreatic cancer

The most common surgery for pancreatic cancer, one of the deadliest forms of cancer, involves the removal of the pancreas, as well as part of the stomach, small intestine and bile duct. It’s a major operation with many potential complications. Not only that, but recovery can be long, and not all surgeons can perform the procedure. This leaves many sufferers, who often have only months to live, without hope (the one-year survival rate for pancreatic cancer is around 20 percent), and it’s why scientists are constantly on the lookout for new ways to treat the disease.

“The treatment options are not good. The tools and approaches have not evolved, primarily because it’s such a difficult disease to diagnose,” says Robert Van Buskirk, professor of biological sciences at Binghamton University.

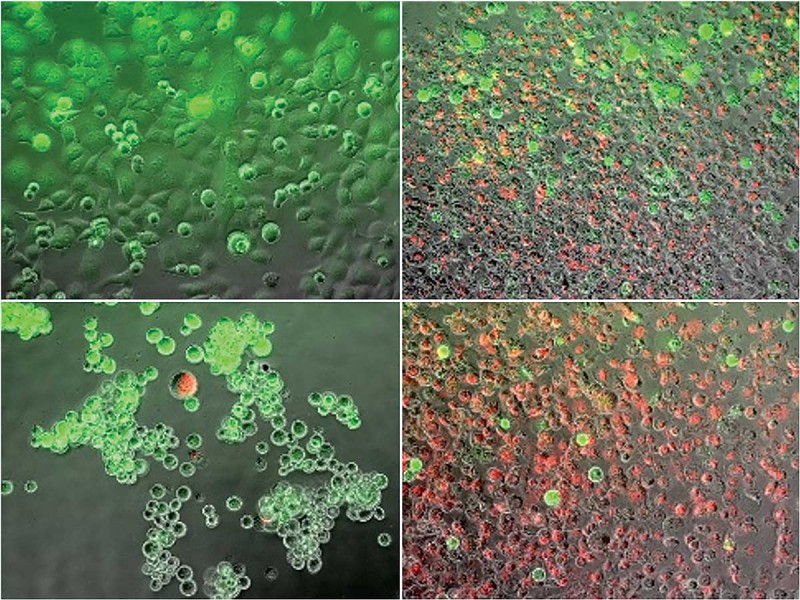

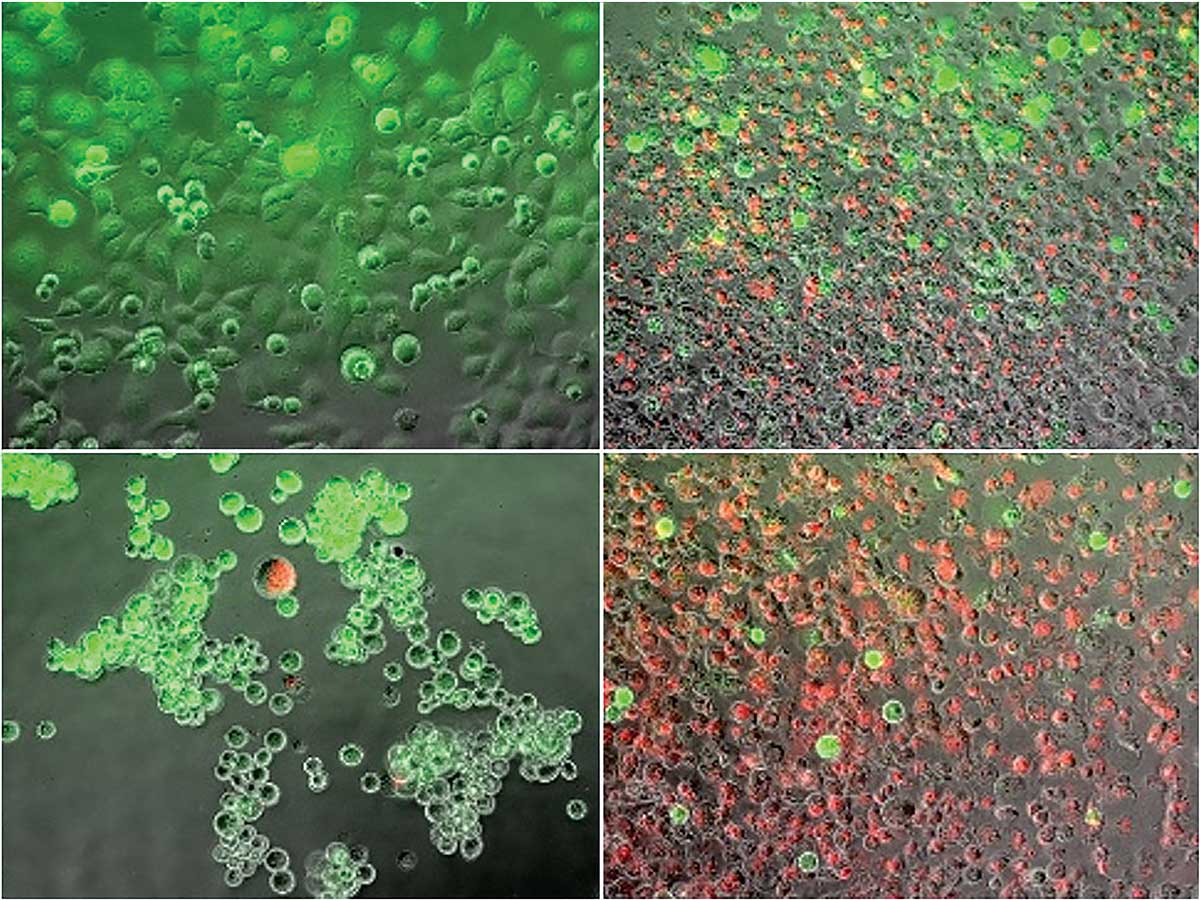

Van Buskirk and a team of academic and industry researchers, including Binghamton graduate student Kenneth Baumann, have been experimenting with a combined heating and freezing process known as dual thermal ablation to tackle the disease. They heated and froze cancer cells and then looked at how many cells died, the rate of regrowth of surviving cells and which cell stress-pathways were activated. They found that this technique may provide an alternative adjunctive path for killing cancer cells beyond heat or cryoablation alone, and their findings were published February 2018 in the peer-reviewed journal Liver and Pancreatic Sciences.

“There is no one therapeutic approach that is the be-all, end-all for all cancers,” says John G. Baust, professor of biological sciences and director of Binghamton University’s Institute of Biomedical Technology. “We understand that cryoablation is very effective, but it has its weaknesses. We understand heat is very effective, but it also has its weaknesses. So, by combining the two, can we give a one-two punch and overcome those weaknesses to give a morerobust therapeutic path?”

Van Buskirk and Baust, in collaboration with CPSI Biotech, the med-tech company based in Owego, N.Y., that is leading this project, are conducting further research into ablative therapy and evaluating new catheter technologies to deliver the treatment to patients. The team says, ideally, the procedure would work like this: A doctor would run an endoscope, outfitted with a special dual ablation probe, down the patient’s throat to reach the affected area, where five minutes of heat would be applied, followed by five minutes of freezing. The patient would return home that day; no overnight stay, no extended recovery.

“It’s not a scheduled, recurring treatment option like chemotherapy. It’s a much different, minimally invasive, focal strategy,” Van Buskirk says. “It’s a one-shot deal. In, treat, go home, monitor.”

Not all patients will be candidates for the treatment, but the researchers estimate that as many as 30 percent of pancreatic cancer patients could benefit.

“If we were able to impact 10 percent of the patients out there, that would be amazing. That would be tens of thousands of patients a year worldwide that could be treated with this approach,” Baust says.

That would certainly please Leslie Kohman, MD, director of outreach at Upstate Cancer Center and chair of the upstate New York board of the American Cancer Society, who estimates that 44,000 people will die from the disease this year alone in the United States. She says it’s important to pursue all fronts in all kinds of cancer research, because you never know what segments of patients are going to be able to benefit.

“If it’s as good as surgery and much less invasive, it will be a huge advance for patients, because when they have this big operation it takes a while to recover,” Kohman says. “And while they’re recovering, they’re not having chemotherapy or radiation, because they’re not recovered enough yet, so it delays the treatment. If this local ablation could be done so they could then get right on with their radiation and chemotherapy, or targeted therapy or immunotherapy, that would be an advance.”

The team has a lot of work ahead of them before their dual thermal ablation technique is used on actual patients. They’re studying which stress pathways specifically cause pancreatic cancer cells to die, in order to make the heating and freezing ablation process more effective. CPSI is developing new catheter technologies to deliver the treatment. And they’re looking to raise money, through grants and investments, hoping to move to phase-one clinical trials within the next two years.

“It’s important for everyone to understand that we’re still a few years off from clinicals,” Baust says. “It’s heartbreaking when we take phone calls from patients who see things in the news and they’re like, ‘Oh, how can we get this treatment tomorrow?’ As a team, we’re pushing hard to get there.”