Seabiscuit’s Secret

Binghamton scientists use DNA to explain horse’s success

The story of the underdog is sewn into the fabric of American culture. The tale of the nobody who musters the strength to become a champion, attracting supporters along the way and leaving naysayers with their jaws on the floor is forever compelling.

During the Great Depression, a time when Americans were looking for someone — or something — to root for, an underdog came along in the form of a small, lazy Thoroughbred named Seabiscuit. After losing his first 17 races, Seabiscuit became a star with a sudden streak of against-the-odds victories.

“Out of nowhere, Seabiscuit inspired hope at a time in our history when people were really struggling. He had more newspaper headlines than many other notable public figures at the time, and people were really taking note of his accomplishments,” says Jacqueline Cooper, president emeritus of the Seabiscuit Heritage Foundation.

Seabiscuit’s rise to the top culminated in the 1938 “Match of the Century” race against Triple Crown winner War Admiral. With tens of thousands of fans in the stands at Maryland’s Pimlico Race Course, and millions more listening in at home on the radio, Seabiscuit pulled away during the final stretch of the race and claimed a dramatic victory by four lengths.

“Watching the original footage from the War Admiral race still gives me goosebumps,” Cooper says. “The notoriety this little horse has achieved is quite remarkable.”

Immortalized in a best-selling book by Laura Hillenbrand and an Oscar-nominated film, the story of Seabiscuit has left many wondering what exactly propelled him from zero to hero.

With the help of cutting-edge science and a descendent of Seabiscuit’s owner, a Binghamton University molecular physiologist may have found the answer within the champion’s DNA.

What makes a horse fast?

While he’s always had an interest in horses, Associate Professor Steven Tammariello never anticipated how much they’d actually be involved in his research.

“I’ve always looked at horse racing as this magical kind of sport. I grew up going to a really small race track, and I’ve always loved it,” Tammariello says.

When he first came to Binghamton University, he studied the molecular regulation of neurodegeneration using models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases. But as time went on, his interest in horses started finding its way into his work.

“I wondered if anyone had ever looked at the genetics of racehorses, and I thought it was a fascinating interaction between my knowledge of genetics and genomics, and my interest in horse racing,” he says.

Partnering with other Binghamton faculty, Tammariello established the Institute for Equine Genomics and started testing gene variants found in horses of all skill levels, hoping to determine what exactly makes a good racehorse.

He also started his own company, Thorough- Gen LLC, genetically testing horses around the country to give owners insight into the potential of their Thoroughbreds. As he discussed his method at conferences, he began making a name for himself in the world of horse racing.

It was at one such conference that his work caught the attention of Cooper, who owned a fifth-generation descendant of Seabiscuit named Bronze Sea. Cooper, who lives at Ridgewood Ranch (the Northern California home of Seabiscuit) had long had an interest in preserving Seabiscuit’s legacy.

“I wanted to know if it would be possible to see which of Bronze Sea’s traits stemmed from Seabiscuit. We realized pretty quickly that would be very difficult to do, considering we didn’t have any DNA from Seabiscuit [who died in 1947],” Cooper says.

Looking for a solution, Cooper brought Col. Michael Howard, the great-grandson of Seabiscuit’s owner, Charles Howard, into the conversation to see if he had any suggestions. While Seabiscuit was buried in an undisclosed grave at Ridgewood Ranch, they wondered if an old brush with some of the champion’s hair still existed.

What Michael Howard had in mind was well beyond anything they could have imagined.

“Col. Howard told us, to our surprise, that not only do Seabiscuit’s silvered hooves exist, but that we would be able to borrow them for testing,” Cooper says.

Seabiscuit’s hooves had been removed and silvered after his death, and were on display at the California Thoroughbred Foundation. While this practice is no longer customary, it was once common to silver the hooves of champion racehorses to use as keepsakes or even cigarette dishes.

Despite their age and condition, the hooves potentially held testable DNA.

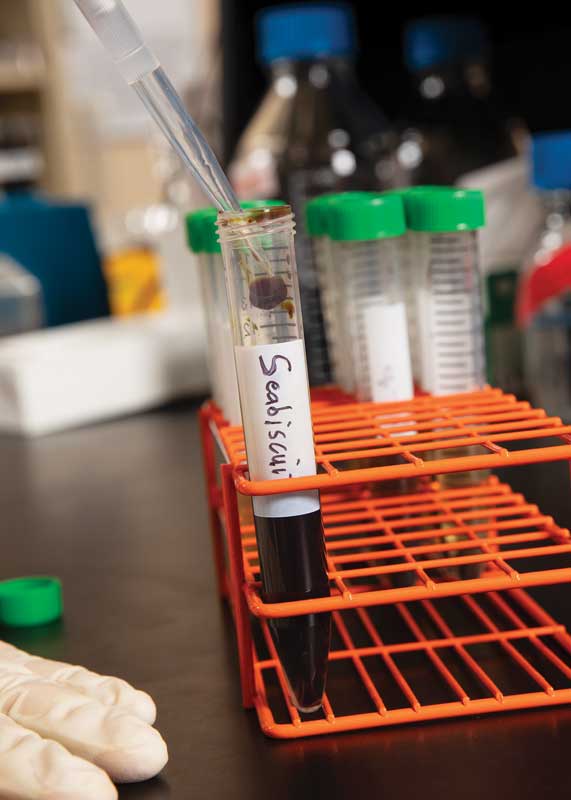

“I wasn’t sure what we’d find, but we decided to have them sent to Binghamton to see what we could do,” Tammariello says.

Stamina and speed

To say that biological anthropology PhD student Kate DeRosa, MA ’16, was skeptical that the researchers would find anything useful within the two hooves that were sent to Binghamton would be an understatement.

“Preservatives can really degrade DNA, and we weren’t actually sure what these hooves were preserved with. All we knew was that they were preserved and silvered,” says DeRosa, whom Tammariello enlisted to help with the project. “Metals can also cause problems — not only the silver, but horseshoes could have influenced the DNA results as well.”

The researchers also didn’t know if the coffin bone (where the DNA would be) had been removed from the hooves during the silvering process, and wouldn’t know until they started drilling into them.

“The stuff on the outside of the hoof is essentially like a fingernail, and it’s not ideal to extract DNA out of a fingernail. So, we really had to carefully drill our way in without damaging anything or touching the silver,” Tammariello says.

The procedure took place in Binghamton’s ancient-DNA and forensic laboratory. At first, the drilling produced only brown powder — a sign that there wasn’t anything usable to test within the hooves.

“The more you drill, the more intense it gets, because you have to keep going deeper and deeper to get to the coffin bone — if it’s even there,” DeRosa says. “It’s both exciting and stressful.”

Much to her relief, the powder started turning white as DeRosa got below the “frog” of the hoof — a sign that the coffin bone was intact.

The DNA that the researchers extracted was degraded, but usable. The mitochondrial DNA, though, was intact and was used to verify the maternal lineage of the samples and confirm that the hooves, in fact, belonged to Seabiscuit.

“While these hooves have belonged to the Howard family since Seabiscuit’s death, it’s important to make sure you can scientifically guarantee that they were his,” Tammariello says.

From there, they were able to partially sequence specific genes often found in wellperforming Thoroughbreds. Their results showed that Seabiscuit had gene variants often found in good distance runners, as well as underlying variants that were often found in sprinting horses.

“We found that Seabiscuit’s genotype was very suggestive of what his actual race record was,” Tammariello says. “He won very short races that required sprinting, but he also won much longer races that required stamina and distance.”

According to Tammariello, this combination of stamina and speed in Seabiscuit’s genotype is rare nowadays, as today’s horses are bred more for speed than distance.

The researchers even found a possible explanation for why Seabiscuit was such a late bloomer.

“His genotype suggests he would not have been a precocious runner, meaning he would have taken a long time to develop,” Tammariello says. “It’s not a genotype that suggests he’d be winning as a 2-year-old. He didn’t start winning until later in his career.”

The will to win

Testing the DNA of one of the most famous horses in the world was not a project DeRosa ever expected to work on, but she says it’s emblematic of the experiential opportunities that students have the potential to take part in at Binghamton University.

“This is kind of a strange claim to fame that could make for some interesting icebreakers in the future,” she says, laughing. “But it’s also exciting to see so many people take interest in this research.”

While their findings are significant, they only scratch the surface of what the researchers hope to discover from Seabiscuit’s other two hooves, which arrived on campus in February.

“Since we did this first extraction, there have been new methods that have come out for even better testing,” DeRosa says.

But they’ll need to know what they’re looking for.

“DNA is not unlimited,” she says. “You have to choose carefully what to do with it because it begins to degrade once you extract it.”

Tammariello hopes to dive further into the physiological elements that made Seabiscuit such an outstanding racer.

“We’re really interested in taking a look at genes that affect behaviors and traits like aggression and trainability. Despite being this small and lazy horse, he developed this will to win and refused to lose,” Tammariello says. “Horses like that are remarkable. Even if he wasn’t physically a good-looking horse, he had behaviors that wouldn’t allow him to lose.”

Ultimately, Tammariello hopes to get a full picture of not only what made Seabiscuit such a champion, but also of how he differs from modern racehorses.

“This is the culmination of everything we know about the genetics of Thoroughbred racing, and it will allow us to assess this horse and really get an idea of what he had under his hood,” Tammariello says.

It’s been just over 80 years since Seabiscuit’s historic victory over War Admiral. While such legends run the risk of becoming more myth than fact as time passes, Cooper believes the exploration of Seabiscuit’s DNA helps keep his too-good-to-be-true story grounded in reality.

“We have the story of this historic figure, and we have the book and we have the movie, and now, scientifically, we have a way of confirming that the story is factual,” she says.

“The DNA proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that this story is true and it is exciting.”