Binghamton gains two Books of Hours

Medieval manuscripts must be experienced, not just read

Medieval manuscripts carry a certain animal smell, a slightly brittle texture. Weighted down by centuries of history, these objects feel precious, maybe imbued with a little magic. Touching one is an experience that can’t entirely be replicated by even the most high-quality image on a screen.

That’s what makes Binghamton University’s recent acquisition of two parchment manuscripts of French Books of Hours so significant.

“There’s something about having the artifact that’s central,” says Marilynn Desmond, distinguished professor of English. “As everything becomes digitized, we’re becoming more aware of the power of the artifact, not less.”

Desmond was working on her dissertation at the University of California, Berkeley before she touched a medieval text. In 1985, during a fellowship in England, she had an opportunity to work with manuscripts of Virgil. “They’re speaking to you from centuries earlier,” Desmond says. “I had been reading and working on medieval texts, but I hadn’t thought of them in their materiality until then. I never had that luxury as an undergraduate.”

Her colleague Bridget Whearty, an assistant professor of English, had been admitted to a doctoral program to become a medievalist before she touched a medieval book.

“Like so many people, my only experience with medieval anything came from reading modern printed books, looking at objects in museums or watching TV, where other people touched and talked about medieval things,” Whearty says. “I’m excited to share these manuscripts with Binghamton students and the community. History isn’t just something that belongs to other people. These books are ours. We get to tell their stories.”

The acquisition

When Binghamton set its sights on acquiring a Book of Hours, a small team quickly coalesced around the idea, says Desmond, a former director of Binghamton University’s Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies (CEMERS).

Two Binghamton graduates — Alex Huppé ’69 and William Voelkle ’61 — played key roles in the chase and helped line up additional support.

Huppé’s father, Bernard F. Huppé, and Aldo Bernardo, both founding faculty members of Harpur College, helped establish CEMERS, the oldest organized research center at Binghamton University, more than 50 years ago. Alex Huppé contributes regularly to a special fund, the Bernard F. Huppé Endowment for Special Collections. That fund, as well as the Aldo and Reta Bernardo Fund, provided seed money to buy a Book of Hours.

Meanwhile, Voelkle, emeritus curator of medieval and Renaissance manuscripts at the Morgan Library and Museum in Manhattan, suggested that Desmond approach the B.H. Breslauer Foundation, which offers grants to libraries and nonprofits to ensure public access to rare books and manuscripts.

The first Books of Hours that Desmond looked at were priced between $60,000 and $70,000.

“The best ones are illustrated, and they’re extremely expensive,” she says.

Voelkle felt Binghamton would get a better deal through an auction, rather than from a bookseller. In November 2018, there was a promising Book of Hours on sale in New York, and the Binghamton team put together $65,000 to bid on it. The book sold for $95,000.

In December 2018, Christie’s London listed four Books of Hours in a single auction.

“We didn’t get our hopes up after our initial experience of being so outbid,” Desmond says. Still, she was going to be in England, and she decided to go look at the books.

Two of the Books of Hours seemed promising. Desmond had a slight preference for one, and the other was coming up for auction first. Strategically, it made sense to pursue the second book because it was a better fit for CEMERS.

Michelle Gardner, senior director of foundation relations, bid on Binghamton’s behalf. Desmond watched the auction live on her computer from Cambridge.

The first book didn’t reach the minimum bid and was withdrawn from the auction.

The second went for $26,000, not much over the minimum.

“It was weird,” Desmond says. “We got it! I knew that we were the winning bid.”

Later that day, the Breslauer Foundation’s president sent Desmond a text to ask if she also wanted to buy the other manuscript. Binghamton hadn’t used up its grant.

Desmond called Olivia Holmes, professor of English and the current director of CEMERS, to see if the center would put up the $5,000 required as seed money toward the second manuscript. Holmes agreed to use money from the Bernardo Fund.

The Breslauer Foundation approached the owner of the second book through Christie’s, and that’s how Binghamton ended up with what Desmond describes as an “unexpected bounty” of two Books of Hours in one day.

The manuscripts

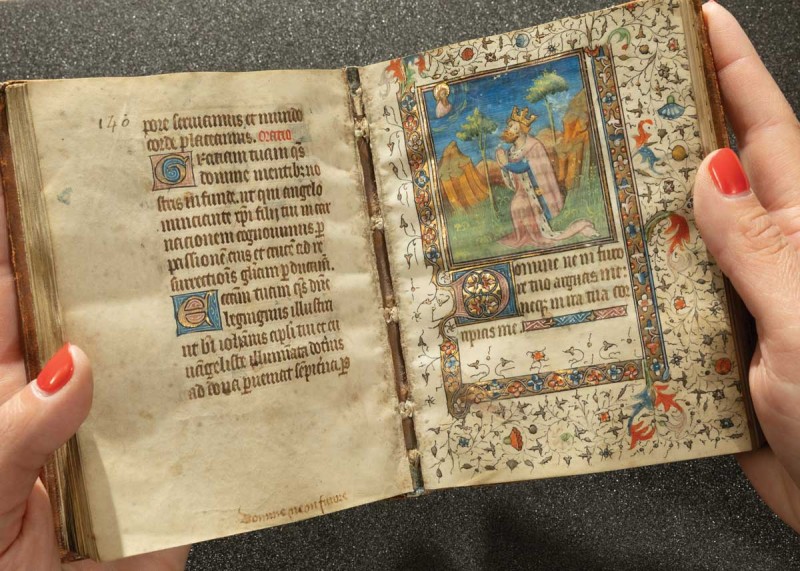

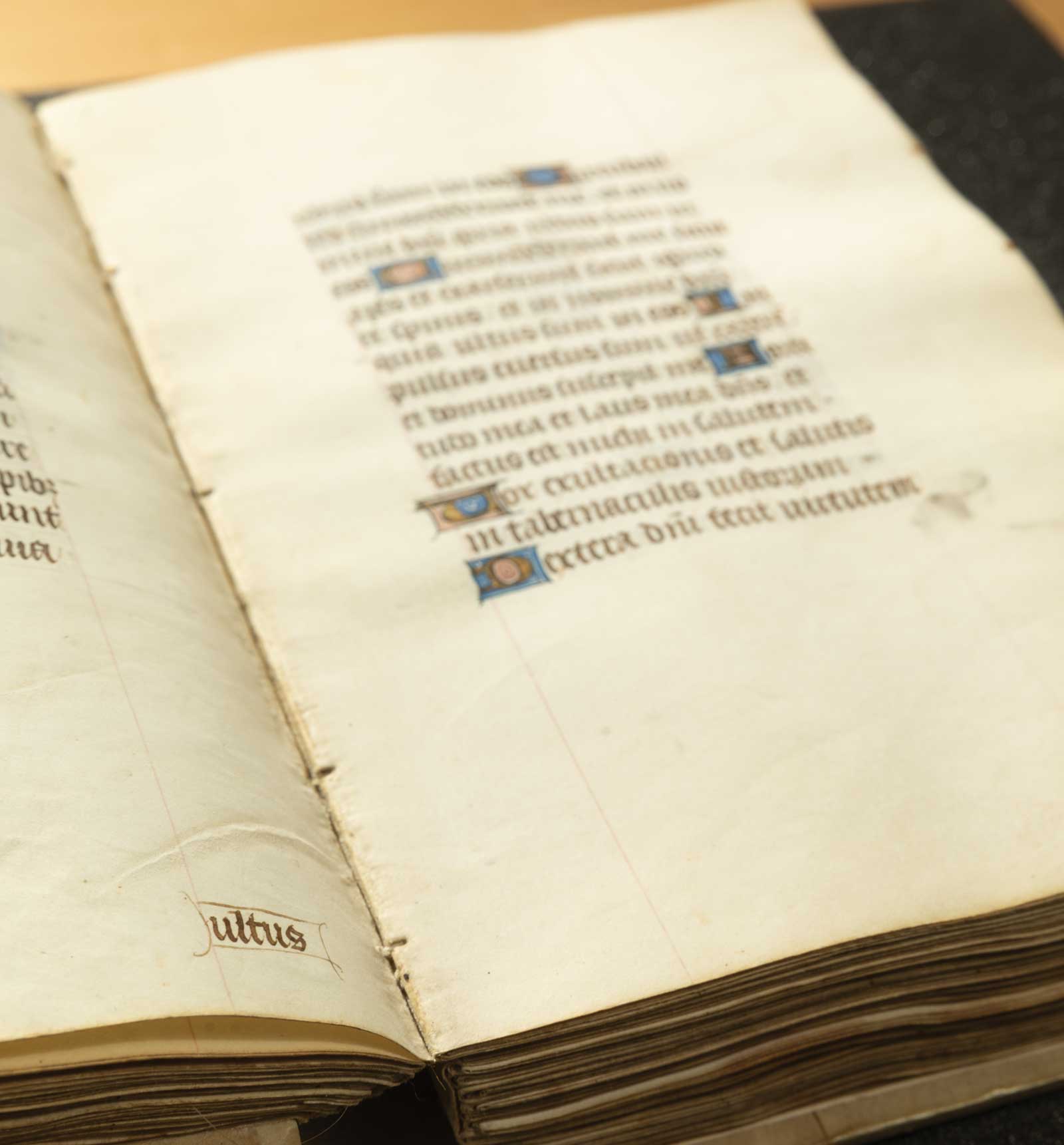

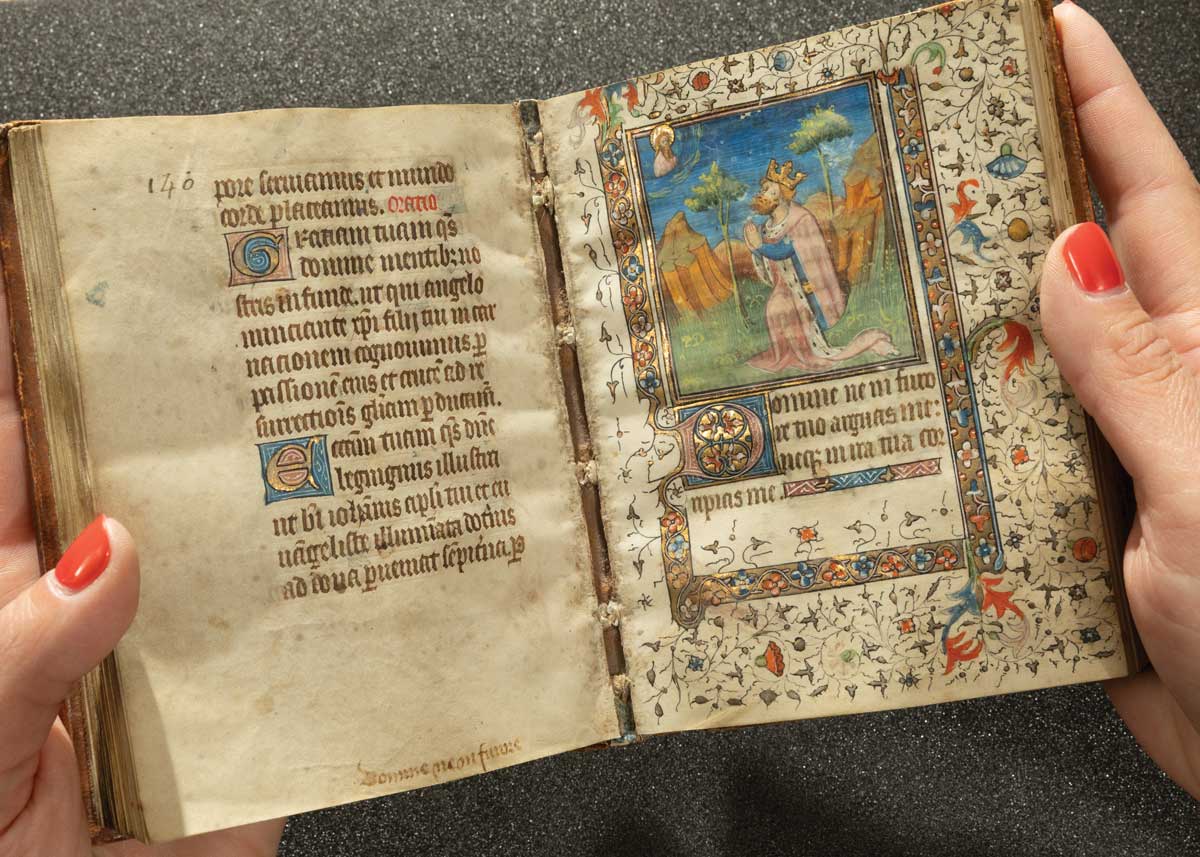

The larger book, the one Desmond initially chose, is known as the De La Grange-Languet Hours. It was created between 1450 and 1475. On some pages, there are handwritten family records added in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The smaller book, a Parisian Book of Hours, is slightly older, dating to the second quarter of the 15th century. It also has family records added in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Both books were re-bound in the 18th century and are well preserved. Neither has been digitized so far, though the Binghamton team hopes that will be possible in the future.

The two illuminated manuscripts each feature several miniatures; small paintings within the text. “These illustrations have their own power,” Desmond says. “They make the books even more compelling.”

Whearty notes that the books were written by hand around the same time that movable type was introduced in Europe. “They’re part of this larger culture of bookishness,” she says. “The reason that there’s even a market for print is because of books like these.”

Part of each Book of Hours acts like a day planner, with a calendar of major feast days.

Looking at the month of February side by side in the two books, it’s easy to spot some interesting variations. One lists certain dates in red; the other in gold.

“That’s the indication of the major feasts,” Whearty says. “If you’ve ever heard the phrase ‘red-letter day,’ that’s what this is from. The person who paid for this book was not satisfied with red letters. No, no. We need liquid gold!”

After the calendar portion in the larger book, there’s room for notes and prayers in Latin and French. In the smaller book, gospel lessons follow the calendar.

Objects of devotion

These books were devotionals and would have been used seven times a day, every day.

Back then, Whearty says, people didn’t read silently. “The act of reading would be an act of quiet muttering,” she says.

While the books reveal something about their initial owners’ wealth and religious devotion, they were more than fancy calendars for rich people to show off at church. They were passed from generation to generation, treasured objects that connected people to their family.

Librarian Blythe Roveland-Brenton, head of Special Collections at Binghamton, says the books allow us to imagine time measured in people. “I just love the signs of how they were used, how they were read and how they were treasured,” she says. “These books are beautiful, but they’re not pristine.”

Whearty says scholars are interested in the kind of destruction that comes from too much loving. Pointing to a page where the text is smeared, she says: “It might be a sign of devotional kissing. They might have been kissing the book so much that it smudged.”

Inherently interdisciplinary

A collaborative spirit is visible when Desmond, Whearty and Roveland-Brenton talk about their experiences with the Books of Hours.

Whearty, looking at a page illustrating the Annunciation, notes that Mary wears blue. The pigment was made with lapis lazuli, mined only in present-day Afghanistan. “Blue is the most expensive thing,” she says. “The best blue is made of ground-up semiprecious stone that is transported thousands of miles.”

Here’s where the books will be of interest to scholars far beyond medieval studies: What does Mary’s robe tell us about chemical compositions of pigments? Trade routes of the era?

Desmond says these manuscripts exemplify the interdisciplinary enterprise of medieval studies. Both books are in Latin and French, while the illustrations require the expertise of an art historian. As devotional objects, these Books of Hours offer historical evidence of medieval Christian practice, particularly by women, who frequently owned and used them.

Roveland-Brenton sees her role as striking a balance between preserving the books and making them accessible. “We don’t have these so that they’re locked in a vault,” she says.

Whearty sees the texts dovetailing with Binghamton’s emphasis on undergraduate research in the humanities. “The smartest students we have here are just as smart as the top students anywhere,” she says. “But our students are less packaged, less guarded. They let themselves get geekier. They are excited about things. They ask questions, which is why this is so perfect. There are so many questions that have yet to be asked about these manuscripts.”

It’s special for a public institution to have access to and ownership of this history.

“This says that history matters, that the humanities matter, that Binghamton is a place that takes primary-source documents from the Middle Ages seriously,” Whearty says. “We put them in the hands of our graduate students, our undergrads and our faculty. It makes a statement about our institutional commitments. It makes us stand out.”