A surprise in the archives

Biology student uncovers Lincoln, Booth autopsy reports while conducting research for history class

Acadia Parker steps off the Metro into the center of Washington, D.C., and crosses the National Mall, passing the Capitol Building and the National Gallery of Art.

She enters the National Archives Research Center and says, “I’m here to look at some records.” The person at the desk tells her to go around back.

Soon, Parker clears multiple security checks. She files a request for the records she wants, gleaned from a footnote found in her reading. She feels uneasy, knowing the archivists are used to dealing with professionals. She receives gloves and special paper to take notes — no notebooks allowed. Finally, she’s left alone in a reading room with the records.

There, Parker uncovers what she least expects to find: the autopsy reports of a United States president and his assassin.

The science of history

Parker, a sophomore biology major from Rochester, N.Y., visited the National Archives in November.

“What’s that movie where he steals the Declaration of Independence?” she says, referring to the 2004 Nicolas Cage film National Treasure. “That’s where I was.”

Parker was enrolled in a seminar course called Civil War and Medicine, taught by Diane Sommerville, professor of history, in fall 2018. Sommerville, a Civil War specialist, says medicine of the era is a growing field of study for historians.

As a sophomore nonhistory major, Parker had to receive special permission from Sommerville to enroll in the senior seminar.

“I was trying to scare her off a little bit, because the subject is cool but there’s a lot of work that you have to do that you may not be used to doing in the sciences,” Sommerville says. “She said, ‘I definitely want to do it.’”

Since Parker is on the pre-veterinary track, she chose the class as an elective to learn about the history of medicine.

“I think it’s important to value history for future decisions, especially when it comes to medicine, because there’s so much we can learn from the past,” Parker says. “We have to learn from our mistakes.”

For her, this is more than a medical philosophy. It’s her life motto, and she seeks to incorporate it into everything she does.

Parker chose to write about Civil War-era autopsy reports for her final project for the course, a primary source-based essay.

“I’ve always struggled with this idea that people are so different, so I try to look for the things that connect them. One of the things that connects them is that we all have the same end,” she says. “My topic was about finding medical significance in the dead bodies, because there were a lot of them. I was trying to learn something from all of the people who died, because something good had to come from all the loss.”

Parker titled her essay Mortui Vivos Docent — a phrase she has tattooed on her back that means “the dead teach the living.”

When she decided to analyze autopsies, Parker struggled to find accessible primary sources. As it turns out, Civil War autopsy reports are hard to come by.

While reading books on the subject, she came upon a footnote where the author located Civil War autopsy reports in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

That’s where her adventure began.

A journey to the Archives

Last summer, Parker’s father took a job as an educational program coordinator at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. Her family moved from Rochester so he could take the opportunity. During Thanksgiving break, Parker decided to go to work with her father and then venture to the National Archives herself, to conduct research for her paper.

“A big part of why I went to the archives was because of my parents and the opportunities they’ve afforded me,” she says. “They’ve always encouraged me to be curious and ask questions.”

In fact, some of Parker’s medical interest comes from growing up with a mother who is a nurse practitioner and her childhood experience with disease in her family.

“My brother had cancer when he was little, so I spent a lot of time in the hospital with him,” Parker says. “My mom would bring me into work, too, so I was well-versed in the medical environment.”

Once the archivists gave Parker boxes filled with the documents she needed for her paper, she began reading through the curly, often-illegible script of the 19th century.

Sifting through the ledgers of dead people, Parker was searching for patterns: the most common causes of death and how physicians reported them.

And then she pulled out an autopsy report for John Wilkes Booth, President Abraham Lincoln’s assassin.

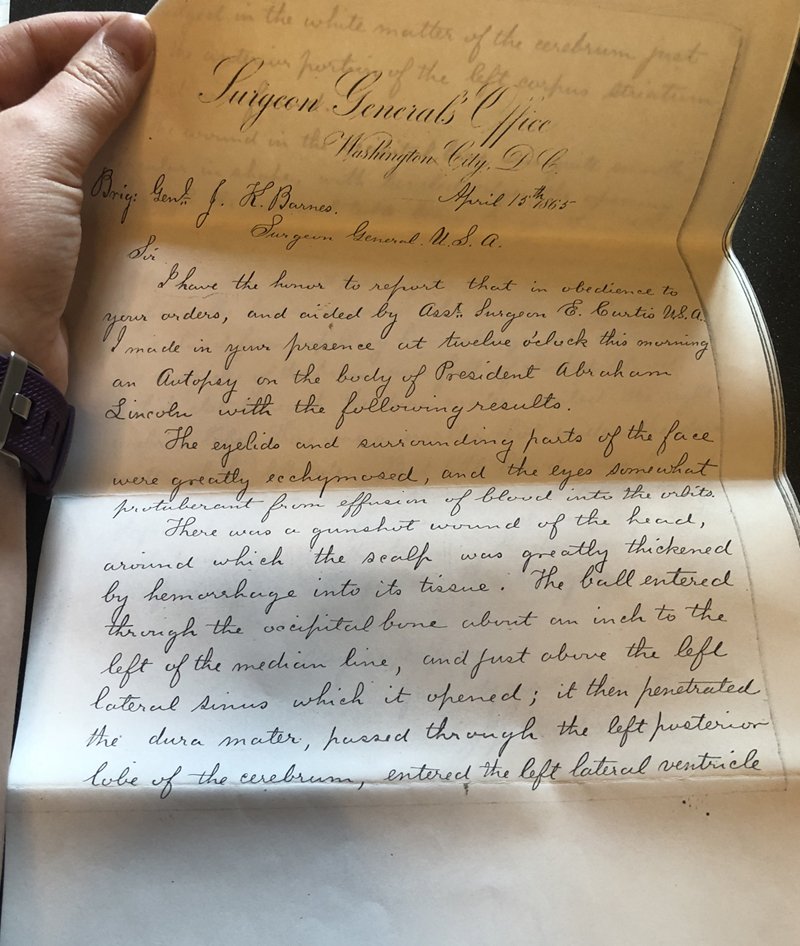

“It was accidental. It was alphabetical: amputations, assassinations, et cetera,” Parker says. “So I pulled the assassinations file, and the first thing I pulled was John Wilkes Booth’s autopsy report. And then the next thing I pulled was Abraham Lincoln’s.”

Parker stopped cold. Hundreds of other death records, and these are the two she pulled? Startled, she walked back to the front desk to make sure the reports weren’t in there by mistake. They could be valuable — normally, repositories keep records of famous people more tightly secured.

“And they looked up the file number and said, ‘No, it’s supposed to be in there,’” she recalls. “It was so rare that I found them. One in a million chance. It’s not like it’s advertised that Abe Lincoln’s autopsy report would be in there. This is a critical part of history that I’m holding. And I didn’t even mean to.”

The dead teach the living

When the initial shock wore off, Parker was able to glean valuable information from the famous historical figures’ autopsies.

For example, in Booth’s autopsy, the medical examiner reported that “paralysis of the entire body [of Booth] was immediate and all the horrors of consciousness of suffering and death must have been present to the deceased during the two hours he lingered.”

Parker wrote about the significance of this statement in her paper: “The report of the autopsy of John Wilkes Booth, Lincoln’s assailant, was medically precise but emotionally charged. The statement was medically irrelevant but included to assuage the nation in a time of tremendous mourning — not only for the death of their president, but the death of their brothers, fathers, sons and cousins.”

Today, autopsies are written on a computer, are much more detailed and often include an accompanying diagram. Civil War-era autopsies were often just a few sentences written by a medical professional explaining what happened.

“What I’ve found is that [during the Civil War] they were very precise. The same things would have been reported today, just in a different way,” Parker says. “It helped learning about forensic medicine, and they were pretty medically advanced at that time.”

The examiners were especially precise when it came to reporting Lincoln’s cause of death, which Parker claimed set an important standard for reporting future presidential assassinations such as John F. Kennedy’s.

“The Civil War allowed physicians to enhance their skills in investigating bodies after they die, because there was such an abundance,” Parker says. “They were able to better understand disease states, and ultimately we have forensic medicine now because we understand how people can die from such horrific injuries.”

Parker took the initiative to dive headfirst into sources she knew would help her write a better paper. Her professor was thrilled.

“I encourage all of my students to go to the archives, but interestingly enough, the only nonhistory major or minor actually took me up on it,” Sommerville says. “The National Archives is really overwhelming. It’s currently one of the biggest repositories in America. So for her to get the gumption to do that took a lot of courage.”

Parker may focus her future studies on veterinary medicine, but in challenging herself to study history at a high level, she got a much bigger picture of her field.

“History teaches a lot of very valuable skills. It teaches critical thinking, analysis, writing. We spend a great deal of time talking about how to organize thoughts, how to organize research, how to build an argument,” Sommerville says. “Frankly, those are skills that most people, even in the STEM fields, could benefit from.”

In preparing for her next endeavor, Parker says she will undoubtedly continue to look at archival material, perhaps for genetic or veterinary research.

“You never know what you’re going to find. Once you’re actually touching the documents and they smell like old tobacco and they have bloodstains on them, you’re like, ‘Wow, I’m touching history,’” she says. “It’s unbelievable to just sit there and lose track of time.”