Professor’s database of 3D facial models is beloved in Hollywood and beyond

Yin named senior member of National Academy of inventors

If you’ve enjoyed a Hollywood blockbuster or played a best-selling video game over the past 15 years, chances are you’ve seen computer-generated faces based on or inspired by the work of Lijun Yin.

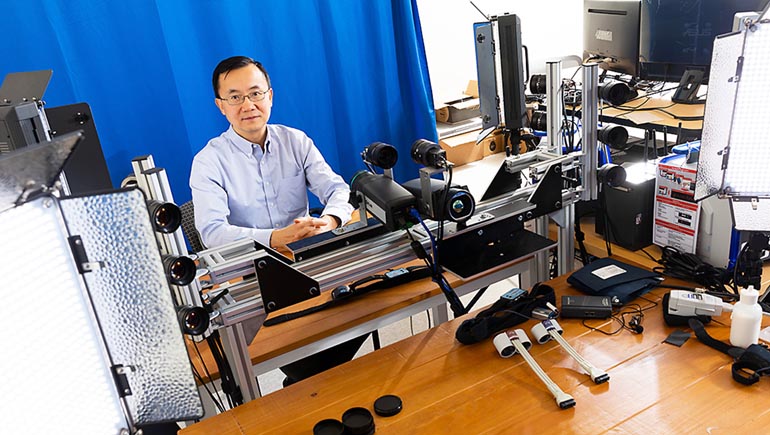

A professor in the Watson School’s Department of Computer Science, Yin has been — and still is — a pioneer in the ever-evolving field of 3D modeling, specifically of the human face. In the early 2000s, other researchers studied human facial expressions through static 2D images or video sequences. However, subtle details are not easily discernible using a flat perspective. Yin saw the problem as an opportunity: “I thought, ‘Why can’t we use 3D models to research human emotions?’ Actual conversations happen in 3D space.”

He and his team have released four groundbreaking facial databases since 2006, with a fifth one in the works. Each iteration has taken advantage of updated technology as well as refined the techniques used to capture the images.

Hundreds of faces showing a wide spectrum of emotions — from anger and fear to happiness and sadness — are offered to researchers and licensed for commercial clients.

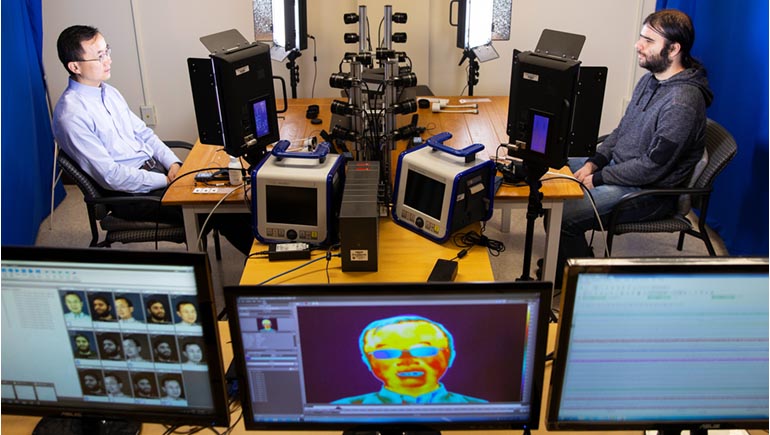

Yin’s Graphics and Image Computing Laboratory (GAIC) at Binghamton’s Innovative Technologies Complex is likely the most advanced in the United States, with its 18 cameras to capture images of faces from all angles as well as in infrared. A device strapped around a subject’s chest monitors breathing and heart rate. So much data is acquired in a 30-minute session that it requires 12 hours of computer processing to render it.

Refined and made smaller, though, such a setup not only could improve facial recognition but also help to create true-to-life 3D avatars for video conferences, games and other online activities. “Maybe someday in the future,” Yin says, “we could conduct an interview without sitting face to face. In virtual space, we could make eye contact. Maybe we could even shake hands virtually.”

In 2021, the National Academy of Inventors (NAI) named Yin a senior member based on the many innovations he has made during his 15 years of research on the facial databases.

The possible applications for the facial database go beyond entertainment and communications. Medical professionals could judge true pain levels in their patients, rather than asking for a subjective 1 to 10 ranking. Plastic surgeons could offer 3D examples of what patients will look like after surgery. Parents could better determine if a crying newborn is sick, hungry or has other critical problems. Law enforcement officials might find it a tool for lie detection.

Yin and one of his PhD students, Umur Ciftci, also are spearheading research to fight “deepfakes” — manipulated videos that show people saying and doing things they did not do. Social media websites have confronted the issue, espe- cially in the political realm, and the technology to make the videos is becoming easier.

Still, Yin prefers to look at the positive side of his work: “You have to be brave enough to imagine what could happen in the future. Without imagination, you cannot make this a reality.”