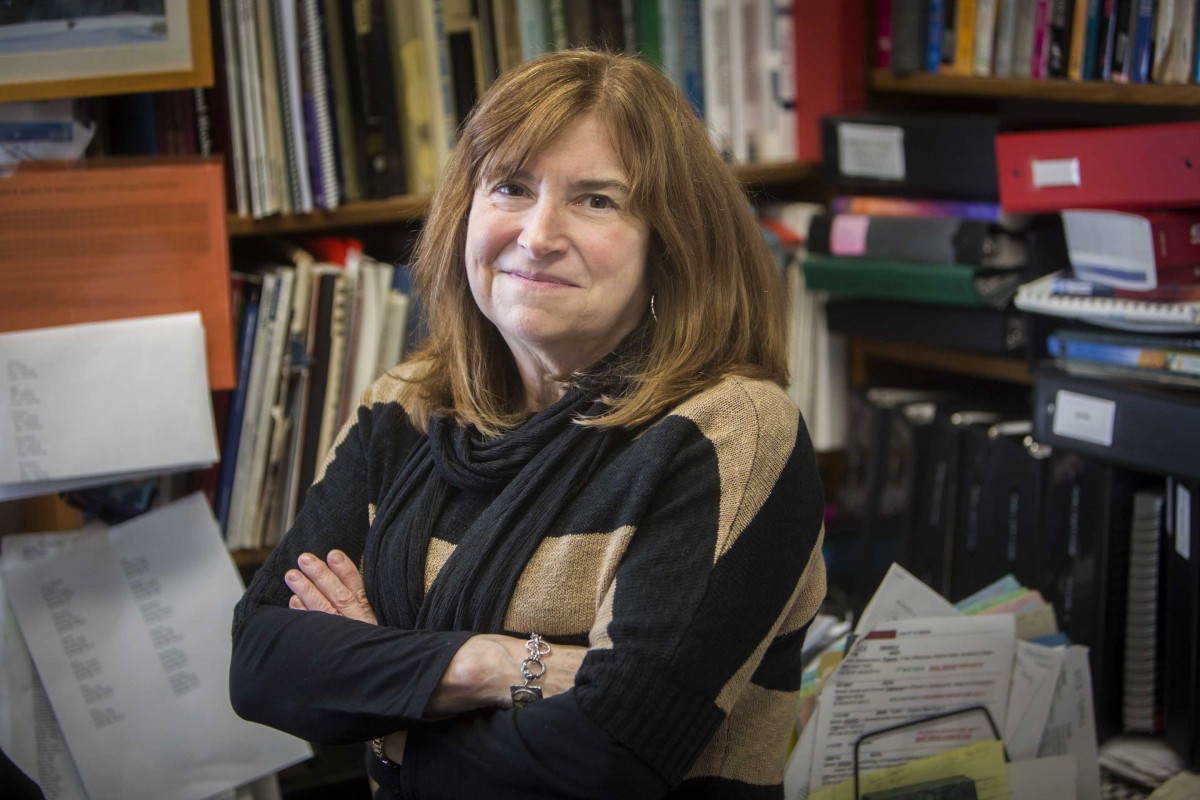

The principal investigator: Linda Spear leaves a legacy in neuroscience

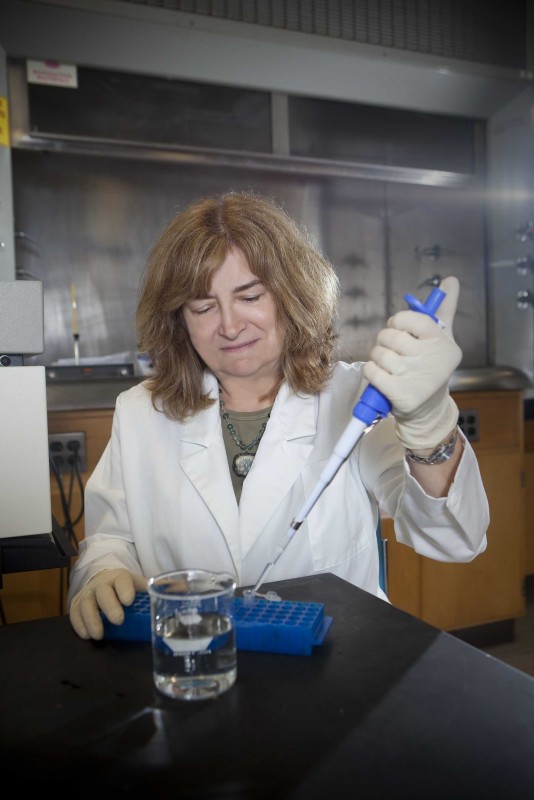

Distinguished Professor Emerita of Psychology Linda Spear greeted new data as a gift: full of excitement for what previously unknown truths the numbers and recorded phenomena contained.

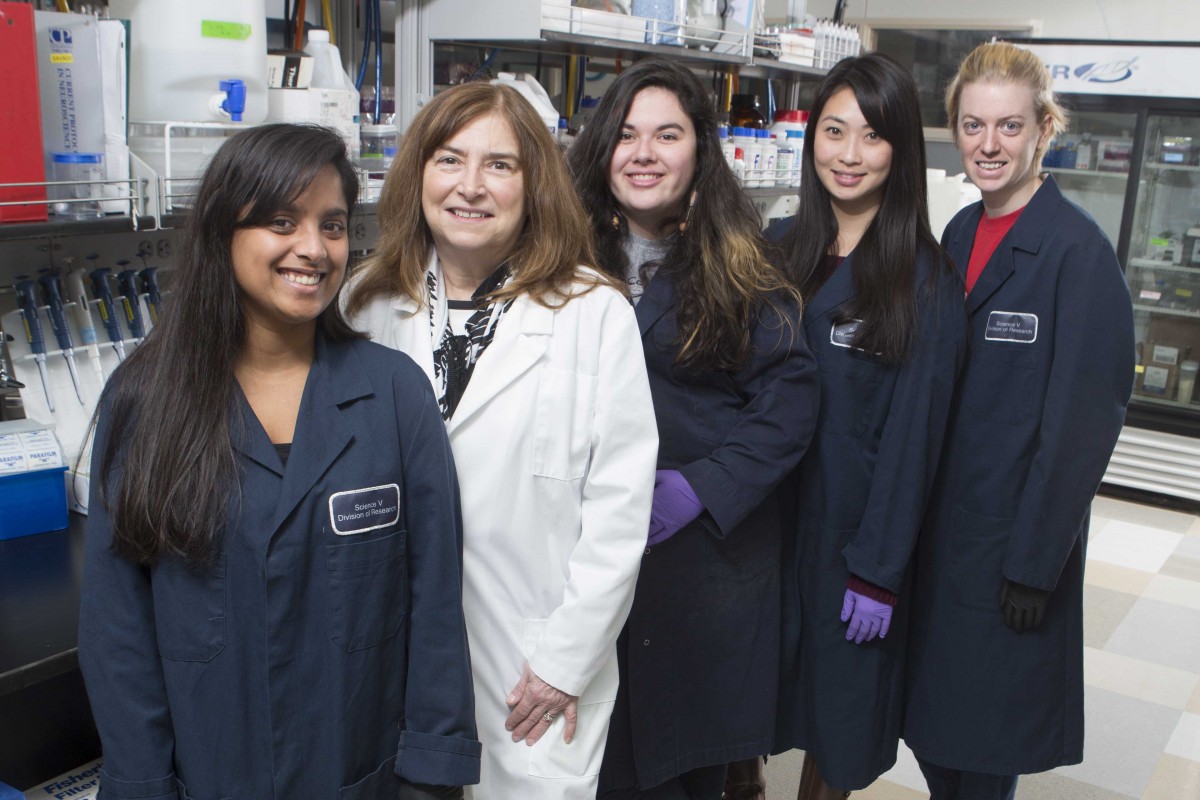

That thrill spilled over to the graduate students in her neuroscience lab, who diligently worked alongside her to unravel the mysteries of the adolescent brain and the developmental surge that makes it vulnerable to substance abuse and addiction. She was both fiercely proud of them and rigorously exacting, shaping them into the next generation of groundbreaking neuroscientists.

Assistant Professor Melissa Morales, who studied with Spear as a graduate student, now runs her own lab in Binghamton University’s School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. Every time new data comes in, she remembers her mentor flashing broad smiles and giving high fives, even if the data represented the potential for only a modest discovery.

“That’s what a principal investigator in a lab is all about. She was a dynamic, curious person,” said Rachel Anderson, who left her native South Carolina to study with Spear and now works as a health science policy analyst with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA).

Spear made a major impact during her decades-long career in neuroscience, authoring or co-authoring more than 300 peer-reviewed publications, giving nearly 460 presentations and heading national organizations. Her groundbreaking research cast new light on adolescence as the last major phase of brain development, with the potential for lifelong behavioral changes.

Along the way, she also shaped the scientists of the future, advising more than 30 master’s students, two dozen doctoral candidates and three post-doctoral researchers, many of them women in what was a traditionally male-dominated field.

She continued her scientific work until two months before her Oct. 13 death from complications associated with glioblastoma, publishing six articles this year alone. One of her last, “Timing Eclipses Amount: The Critical Importance of Intermittency in Alcohol Exposure Effects,” appeared in April’s edition of Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research.

“She was motivated like nobody I’ve ever seen. She just was really driven and loved to solve problems and test hypotheses,” said Professor Terrence Deak, currently director of the Developmental Exposure Alcohol Research Center (DEARC), which Spear helped found in 2009.

A foundational figure

A native of Springfield, Ill., Linda Patia Spear earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology from Western Illinois University and her master’s and doctorate in the field from the University of Florida, where she also did postdoctoral work in neuroscience. She arrived at Binghamton University in 1976, becoming an associate professor in 1983 and full professor in 1988. In 1998, she became the first woman at Binghamton to achieve distinguished professor status.

Spear was the founding director of Binghamton’s undergraduate program in integrative neuroscience — then called psychobiology — 35 years ago, one of the first such majors in the country. She and her husband, Distinguished Professor Emeritus Norman “Skip” Spear, were a powerhouse in psychology and played a major role in growing the program.

One of her most far-reaching publications was “The Adolescent Brain and Age-Related Behavioral Manifestations” in the journal Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews in 2000. Cited by researchers more than 5,500 times, this foundational paper established that adolescence is a critically important developmental period distinct from adulthood across species, and not just limited to puberty.

In humans, that period runs on a spectrum from the ages of approximately 12 to 22, explained Fulton Crews, director of the Bowles Center for Alcohol Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Complex behaviors develop during adolescence related to impulsivity, heightened social interaction, play-fighting and thrill-seeking — in rodents as well as humans.

“There is really a biological maturation of higher cortical function and behavior,” Crews said. “Puppies and ponies, baby deer — you can see the same kind of characteristics.”

Spear was widely considered the top expert in adolescent neurobiology, said Donita Lynn Robinson, assistant dean for graduate education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s School of Medicine.

“The concept of adolescence as a distinct period in developmental psychology had been around for only about a century when Linda began her work, and much of the writing about it had been theoretical. Essentially, it was viewed pretty simply: as a developmental period of ‘storm and strife,’” said Scott Swartzwelder, a Duke University professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences who first met Spear 30 years ago when he began his own research into adolescent alcohol exposure. “Linda broke new ground by studying adolescence on an empirical behavioral level, unearthing specific differences in how the young react to developmental challenges such as drug exposure.”

Robinson, then an assistant professor, began collaborating with Spear in 2009. In addition to her work on adolescence, Spear studied sex differences well before the rest of the field, showing that females and males had some overlapping and other unique aspects of development, behavior and drug sensitivity, she said.

During that same year, Spear was instrumental in the formation of DEARC on campus, initially in partnership with SUNY Upstate Medical University. She served as the center’s scientific director until her death, and as the center director from 2010 through 2017.

“I go to [DEARC] meetings and get fired up and excited because we start talking about research and coming up with all of these ideas,” she mused during an unpublished 2018 interview. “I always leave the meetings energized. There’s not many groups you can say that about.”

During the course of her career, she also compiled a lengthy list of honors, among them the Lois B. DeFleur Faculty Prize for Academic Achievement, the Research Society on Alcoholism’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the Huttenlocher Award from FLUX: The Society for Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, the Neurobiological Teratology Society’s Elsevier Distinguished Lecturer Award and NIAAA’s 10th annual Mark Keller Honorary Lecture Award.

She was also deeply engaged in professional activities on the University and national levels, including terms as president of the Neurobehavioral Teratology Society, the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology and the International Behavioral Neuroscience Society, and was one of the founding members and leaders of the Neurobiology of Adolescent Drinking in Adulthood (NADIA) Consortium, whose membership includes high-profile researchers in the field. Her research and work with NADIA stimulated the National Institutes of Health to start human studies of adolescence, both in terms of substance abuse and brain development, Crews said.

As a clinical psychologist, Distinguished Teaching Professor Emeritus Stephen Lisman didn’t often have the opportunity to work with neuroscientists, and Spear built her own career on animal models. But in 2009, their labs began an unusual collaboration, studying alcohol use among college students hitting the bars on Binghamton’s State Street. During the late-night party scene, graduate students would set up a tent outside where they would measure the impact of drinking on cognition and behavior, and question underage drinkers about their motivations and experience.

When she chaired Binghamton’s Psychology Department, Spear relayed advice she received from her own advisor, the late Distinguished Professor of Psychology Robert Isaacson: Don’t discount the outliers in your data. They can often provide the basis for new ideas and hypotheses.

“’Be curious; don’t just look for what tells you what you want to know,’” Lisman remembered her saying. “She had a real excitement about her data.”

Shaping future scientists

When she began her neuroscience career, Linda Spear was often the only woman in the room, said Associate Professor David Werner, who collaborated with her on alcohol-related research and heard stories of those early days. Like many STEM fields, women are well-represented in the lower echelons of neuroscience but their numbers drop off at the post-doctoral level and beyond, particularly when it comes to tenure-track faculty positions, Deak said.

But for Spear’s graduate students, the role of women in science was simply a norm, said Courtney O’Hagen, now associate professor and chair of SUNY Broome Community College’s Psychology and Human Services Department.

Not only did she mentor students in her lab, but she also mentored junior faculty at Binghamton and beyond. Many of her students went on to make significant contributions of their own to science, such as Marisa Silveri, now associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and director of the Neurodevelopmental Laboratory on Addictions and Mental Health at McLean Hospital.

“I think she would be surprised to realize the breadth of how much of an impact she made on us. Not all of us became scientists, but she launched all of our careers,” O’Hagen said. “All of us are where we are today because of her.”

As a mentor and teacher, she was both tough and encouraging. At any given time, you should be writing up results for a paper, conducting an experiment and designing your next experiment, she told students. No excuses: Just sit down at your computer and bang it out.

But she had her grad students’ backs, too, attending every presentation and modeling work-life balance. She had a rich family life with her husband, children and grandchildren, and mastered a range of hobbies, from tennis to cooking, birdwatching and knitting, Anderson said.

“She understood the importance of family,” said Trevor Towner, a fourth-year doctoral student who uprooted his San Diego family for the opportunity to study with Spear in Binghamton. “She built this amazing home life and tried to instill that in others.”

Always straightforward, Spear threw him into his first research project on the day he walked into the lab. She was upfront in other ways, too, such as when she told her newly arrived graduate student about her diagnosis with glioblastoma.

But Linda Spear refused to let illness get in the way of science or mentorship. She collaborated with Werner and research Professor Elena Varlinskaya to create a mentorship team for her students and to continue her lab’s work, Towner said. As she underwent chemotherapy and radiation sessions, she kept her graduate students and researchers on target, a scientist until the last.

“She was funny and a little quirky. She lived a full, fun life,” Anderson said. “She was basically living a nerd’s dream, doing research all the time, and she loved it. It never occurred to her to be anything other than what she was.”