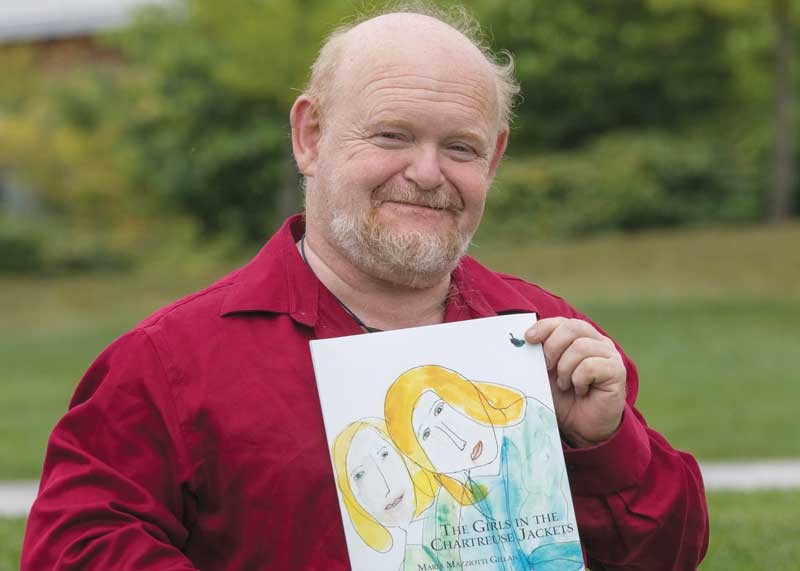

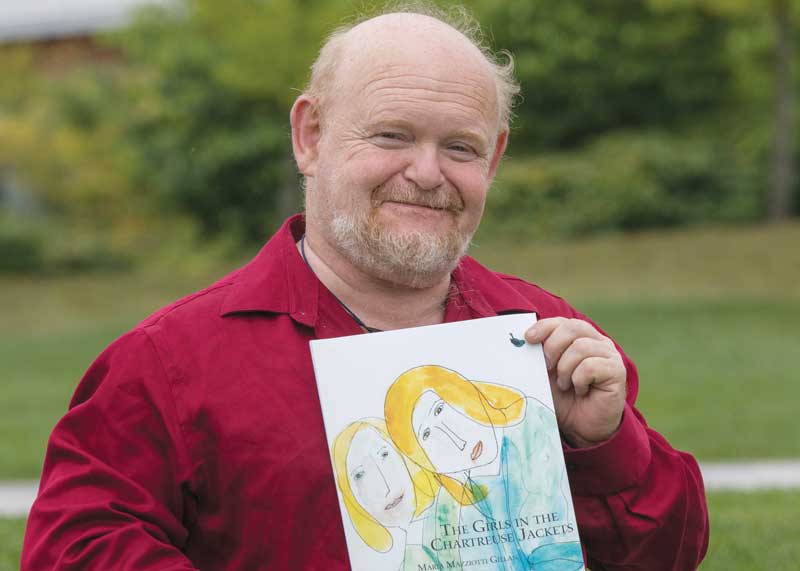

Finding poetry: Joe Weil helps build community with words

Poetry isn’t just limited to sonnets and the linguistic flourishes of a bygone era. It speaks in the language of everyday people, their experiences and the realities around them.

Now an associate professor of English at Binghamton University, poet Joe Weil had his beginnings in working-class Elizabeth, N.J., where his early inspiration came by way of his mother’s five sisters, all talented storytellers.

“They talked in ways that were inventive and often poetic, but they also instilled in me the idea that poetry and music are ordinary parts of everyday life,” he said of his aunts. “We shouldn’t just be an audience. We should all do our bit and participate.”

Inspiration can be found in all manner of places, and Weil’s poetic influences span a broad spectrum: from poets Wallace Stevens, César Vallejo, Miguel Hernandez and Wanda Coleman, to Irish songs, overheard conversations, Marx Brothers comedies and Warner Brother cartoons.

He has published four full-length collections of poetry, along with reviews, essays and short stories, and also co-founded two book publishing ventures. Plus, he has hosted readings and published other poets for years because, he explained, “community is essential to cultivating the individual’s desires.”

“You have to help create the world you wish to live in. We all contain multitudes,” he said.

On a larger scale, that community includes New Jersey’s Geraldine R. Dodge Poetry Festival, which has been part of Weil’s life for nearly 30 years.

The largest poetry event in North America, the festival was once described by former U.S. Poet Laureate Robert Hass as “poetry heaven” and has drawn some of the greatest figures in the field, from Allen Ginsburg, Mary Oliver and Adrienne Rich to Octavio Paz, Ko Un and Yehuda Amichai. Many younger poets give their first reading of note at the Dodge festival, which is held only in even-numbered years.

Weil has read at four Dodge Poetry Festivals, starting in 1992 when the event was held in Waterloo Village in rural northern New Jersey. Since then, it’s moved closer to his urban hometown, “a Number 12 bus ride from downtown Newark,” he said.

Through the years, he’s hosted some of the festival’s conversations and readings, and given workshops as a Geraldine R. Dodge poet in schools. Weil also appeared on Bill Moyers’ “Fooling with Words” in 1998, and was featured by New Jersey’s PBS reading at the festival with National Book Award winner Patricia Smith a decade later.

For the first time, the 2020 festival was held from Oct. 22 through Nov. 1 entirely online due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. Weil was among the featured poets.

Holding a poetry festival on Zoom presents its own set of technical challenges, but streaming should remain an option even after the festival returns to its traditional, in-person format, Weil said. Moving online makes poetry readings accessible to people who otherwise can’t travel or navigate a physical crowd. Weil particularly enjoyed chatting with people in the Zoom breakout room after his pre-recorded reading.

He’s building a poetic community at Binghamton as well. One current project is the Global Imaginary, in which students will reimagine a global poetics by reading and translating poetry in their native languages.

The first reading is scheduled for 7 p.m. Nov. 16, featuring painter-poet and Cuban exile Alejandro Anreus and Mercia Kandukera, a doctoral student from Namibia. Like so many events on campus these days, it will take place in the virtual sphere. Weil hopes, however, that it will someday become an in-person event with food and conversation.

Rather than a rarified precinct of art, poetry draws on everyday speech, honesty and vulnerability to speak to diverse audiences — often at challenging times. The poems students are writing these days are more politically engaged than at any other time in Weil’s teaching career, and the division between the personal and political has, for many, collapsed.

“I think a lot of young people gravitate to poetry at critical moments in their lives. You don’t need to learn how to play an instrument. All you need is your voice and your willingness to express,” he said.

Through their poetry, students confront issues such as patriarchy and systemic racism. Even more traditional topics — love, grief, the search for identity — are imbued with larger implications.

“I think I see a rise in intensity and passion warring with the numbness and torpor that difficult times often engender. Every political rally I’ve attended for Black Lives Matter has included poetry,” Weil reflected. “Poets have once again become witnesses and spokespeople for the consciousness of their age.”