Golden age of poetry: Binghamton alumni pursue the creative life

A ray of light shot a bright finger into Milton Kessler’s Binghamton University classroom. He paused, that day’s lesson plan falling away, and began to recite lines from Theodore Roethke’s “What Can I Tell My Bones?”

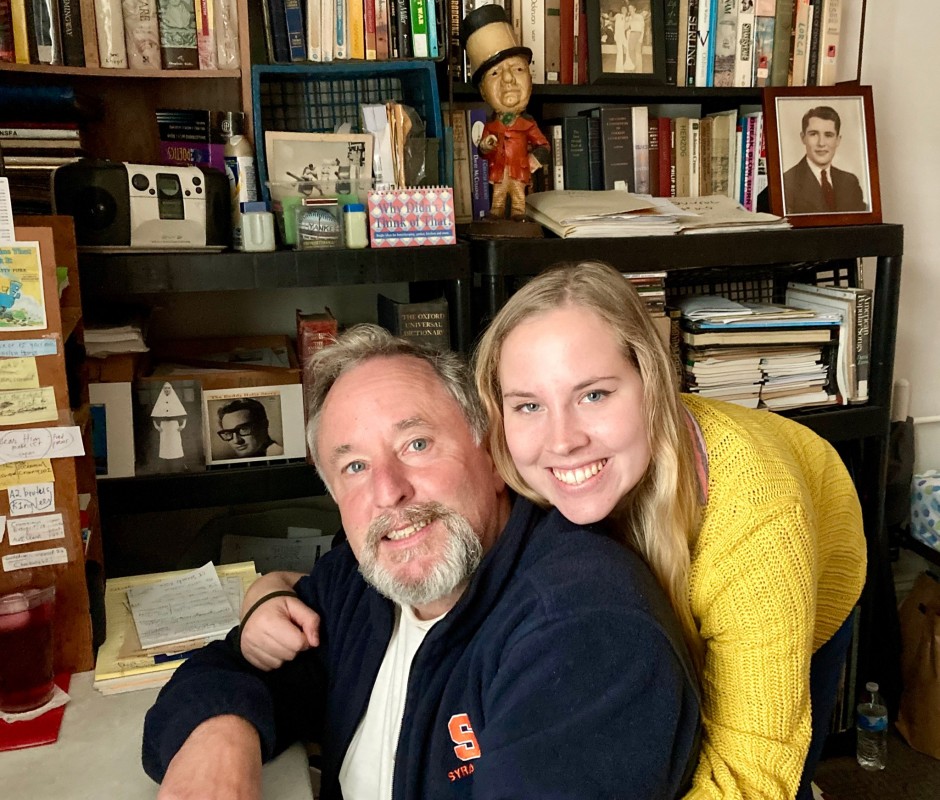

Moments like these stay with Gerry Crinnin and Zack Grabosky, who studied with the late English professor in the 1990s.

“We were lucky to live through nothing less than a golden age of poetry,” Crinnin said during a recent Zoom discussion hosted by Foundlings Press.

Crinnin earned his bachelor’s in English from Harpur College in 1984, earned his master’s at Brown University and then returned to finish his doctorate at Harpur in 1993. Grabosky finished his bachelor’s in English at Harpur in 1992, followed by his master’s in 1994.

The two forged their friendship over poetry, after initially meeting at SUNY Morrisville, where Crinnin worked as a tutor and Grabosky completed his associate degree. Crinnin recommended that Grabosky head to Binghamton to study with Kessler, one of the founders of the creative writing program and “the Mount Rushmore of poetry at Binghamton University,” Crinnin said.

Kessler didn’t bother with the factual rudiments behind poetry, such as the mechanics of writing a sestina. He would tote items to class to spark discussion, his former students said. But wherever that discussion went, the professor would tie it back to history — whether the larger sweep of world events, the personal past or the history of objects, Grabosky remembered.

“He talked about living, and for some reason, that’s what sparked my wanting to write like a maniac,” Crinnin said. “He would be talking about buying groceries in Haifa, Israel, and somehow he made that so interesting to me that I couldn’t wait to go home and start writing about whatever. He just really understood that poetry is everywhere and anywhere. You create the form it needs as you go along.”

Binghamton in the ’90s

One of eight siblings, Crinnin discovered Allen Ginsburg’s poetry on his older brother’s bookshelf, which sparked an interest in Beatnik literature. The Syracuse native worked as a journalist in the Navy for four years and was able to attend Onondaga Community College on the GI Bill. After earning his associate degree, he chose his next college destination randomly by putting his finger on a map of New York state. It landed on Binghamton.

It was only a few years after the 1982 motorcycle crash that claimed the life of acclaimed novelist John Gardner, who also helped found Binghamton’s creative writing program. Echoes of his presence remained, in stories told by the campus community and the subtle scent of his pipe smoke in a subterranean hallway.

Grabosky, a Cazenovia native who initially tried his hand at fiction, found inspiration in professors such as Liz Rosenberg and Ruth Stone. And, of course, there was Kessler. Like an engineer, he would pop open the hood of a poem to find what made it beautiful, Grabosky explained. In that spirit, he would have students tack their poems on the classroom walls.

“And then everybody would have to be completely silent and go around and view them like artworks in a museum,” he said. “I remember him talking about how a poem was like a chunk of rock and you have to break off all the pieces to find what’s really there at the center.”

The two didn’t wait for publishers, but decided to create their own poetry ’zine, Zerograph, run off on a copier and shared with friends, family and the local community. Kessler submitted a poem, as did their fellow students.

Off campus, the Binghamton Community Poets drew a mainly working-class crowd of writers who read their work at local bars. Bar patrons would chime in during open mic nights as impromptu literary critics. Grabosky gave his first real poetry reading during one such evening, inviting his mom.

There is something about the Southern Tier that sparks poetry, the friends reflected: the legacy of Endicott-Johnson and the industrial era, the old neighborhoods with their architecture and the people who lived there, the cheap rents. The Binghamton area had jazz clubs that they frequented, where students had the opportunity to play with the house band.

“It was like cheating, almost, you know, to be living and moving and grooving around Binghamton,” Crinnin said.

“Really, you could walk down the street and almost pluck lines from the air,” Grabosky added.

‘Blazes’ and more

In the intervening years, the two poets went their separate ways but remained friends and continued to create.

Crinnin’s work has appeared in Modern American Poetry, and he’s also published several volumes of his work. In one recent book, I Know You Know, he teamed up with fellow Binghamton alumnus Peter Temes, now a teacher and writer in Seattle. He also made his career teaching the next generation of writers at Jamestown Community College, a job that Kessler helped him land by way of a lengthy and positive letter of recommendation.

After working a variety of jobs, Grabosky now lives in Pennsylvania, where he is a learning specialist at Shippensburg University. He just published his debut collection of poems, Blazes, with Foundlings Press; written over a 30-year span, the poems draw on his journeys through upstate New York and Pennsylvania.

Once the pandemic abates, the poets hope to return to public readings, including Buffalo-area events to celebrate Grabosky’s book. In the meantime, more poems and more books beckon from the horizon, their phrases snatched out of the air of daily life, in all of its beauty.