Alone, Together: Art project documents life during lockdown

A conundrum lies at the center of the lockdown experience. We are alone, sequestered with our immediate family behind locked doors and windows, unable to engage in the common human kindnesses that once structured our lives: hugs, birthday parties, coffee with friends.

At the same time, we go through this lonely time together. Behind each closed door, our lives have an eerie symmetry, a shared experience of solitude.

It’s a dynamic that Binghamton University senior Hadar Arens explores in “Alone, Together,” a documentary project she made in partnership with the Memory Maker Project, a Binghamton-based nonprofit that provides cultural events and advocacy for aging adults, some of whom experience memory loss.

Arens, a psychology major with a double-minor in cinema and applied behavioral analysis, worked remotely with a group of aging adults who shared their pandemic stories and experiences through photography. “Alone, Together” was funded through the Harpur Fellows Program, which provides talented Harpur College undergraduates an opportunity to receive up to $4,000 to design and conduct their own community service project anywhere in the world while school is not in session.

While some fellows choose to make a difference in a country an ocean away, Arens decided to stay in the Binghamton community even before the pandemic hit.

“As a senior in college, I felt that I have received so much from my time here in Binghamton, almost four full years, and I wanted to give back to the community and really engage more with the community as well,” explained the White Plains native.

One of her inspirations for the project was the international nonprofit PhotoVoice, which seeks to empower socially excluded groups through participatory photography. Arens initially expected to spend last summer visiting nursing homes, taking residents’ portraits and having them take photos of their own lives.

The pandemic transformed her lens and her methods, although she retained the focus on therapeutic photography. She ended up doing the project remotely over the winter, communicating with her senior citizen photographers via email and the postal service.

“It ended up turning out even better than I had originally expected,” she said. “With this project, what we did is empower a group of aging adults who are living in isolation, not able to see their loved ones, and empowering them to share their stories through photos.”

The beauty of everyday life

The participants had already been part of the Memory Maker Project, and began meeting regularly on Zoom for weekly talks and art activities once the pandemic hit. They come from throughout the Southern Tier, including such communities as Elmira and Oneonta.

Arens sent them disposable cameras through the mail this winter. After taking photos, the seniors simply mailed the cameras back to her. Some chose to submit smartphone photos instead.

Arens developed the photos in the Bundy Museum of History & Art’s community darkroom, and sent each participant their own set. Because photos of daily life can be intimate, she allowed the participants to choose which ones they would be willing to exhibit in the community.

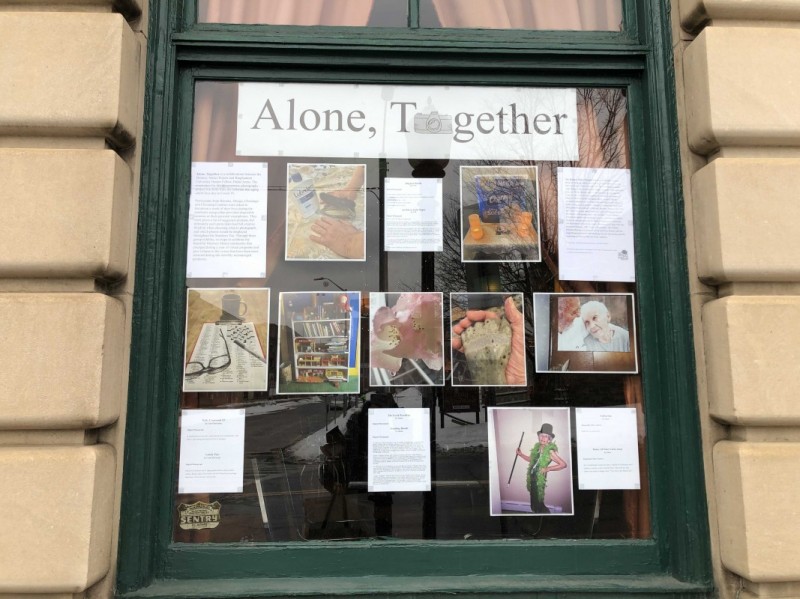

The images show the seniors masked for the world outside the home, as well as quieter moments, such as picking a book from a shelf, sipping a cup of coffee or doing a crossword puzzle. Some were taken by the senior photographers, others by their caregivers or partners. Many of the subjects live alone and isolated, a factor that can impact brain health and memory loss.

The photos are arranged side by side in a grid pattern, putting the subjects in a kind of visual conversation with one another that the realities of social distancing have denied.

“I am fascinated with photographing the mundane, just everyday life. I think there’s something so special in that. We’re becoming much more familiar with the routine as we’re all inside, and finding some sort of spark of beauty in that,” Arens said.

“Alone, Together” is currently on display in Corning, Oneonta, Bainbridge and Binghamton, the last at the Lost Dog Café on Water Street; the exhibits face the sidewalk, making them accessible to passersby. There is a virtual exhibit as well, and plans are in the works for a reception over Zoom.

Her Harpur experience

Arens’ projects have been on public display before. In Cinema Professor Ariana Gerstein’s animation class last year, she and her classmates created artwork encouraging the campus community to vote. The animations were projected on the Library Tower at night for public viewing.

Also last year, a still life photograph she took of citrus fruit was selected for an exhibit in the UHS Wilson Medical Center cafeteria. (Fun fact: Her first name means “citrus tree” in Hebrew.)

She began working for Harpur Edge in her sophomore year as a student associate, connecting her peers with resources to optimize their college experience. She is currently the outreach team lead, collaborating with student organizations and college departments on programs, events and services while overseeing a team of eight people. Harpur Edge programs are currently virtual due to the pandemic, but they continue to offer a variety of opportunities.

“I love working at Harpur Edge. The people who work there, everyone comes from a different major and different background. We’re like a little microcosm of Harpur College,” she said.

Arens cited former Harpur Edge director Wendy Neuberger and current director Erin Cody as playing a major role in her Binghamton experience, promoting a spirit of positivity and encouragement. Her professors, too, have been eager mentors in an array of fields, from Gerstein to art and design lecturer Alicia Sickler Brunelli, Associate Professor of Art and Design Hans Gindlesberger and Psychology Professor Jennifer Gillis.

With both the arts and sciences represented, Arens’ course load combines very disparate elements — but she likes it that way.

“It’s like two puzzles, but these puzzle pieces come together so well,” she reflected. “My professors have all been very supportive of my project and my ideas.”

Gerstein pointed out that Arens is a wonderful example of Binghamton’s interdisciplinary approach to study.

“I have always been aware of her deep interest in finding relationships between psychology, cinema and studio art. Last semester, we had more extensive conversations about how those interests were coalescing around future goals in art therapy,” she said. “She keeps these goals and a search for connections in mind with every project she undertakes.”

After graduation, Arens hopes to visit family in Israel — COVID permitting — that she hasn’t seen in nearly two years, and is also considering volunteer work. Longer term, she plans to pursue graduate school in art therapy, continuing to combine her dual interests in art and psychology.

With the collective trauma of a global pandemic, mental health professionals are needed more than ever, she reflected.

That ties into her experience with “Alone, Together,” which is still offering poignant lessons in the human condition during extraordinary times.

Coping with the pandemic is mentally and emotionally draining, and living in isolation can worsen pre-existing health conditions, she acknowledged. That makes supporting one another — reaching out and offering human connection, even if virtually — especially important. We’re still a community, even if we can’t physically sit with one another.

“Everyone is responsible for supporting a community in their own way, whether it’s directly or indirectly,” she said. “The idea of ‘Alone Together’ builds on this belonging and love in a community. It’s one of our basic human needs to feel seen and heard and validated.”