The Heart of Healing: Alumni physicians inspire the next generation of students

Dr. Adam Fox ’92 knew the rhythms and intensity of medical school long before his orientation. After all, he had already completed podiatry school and a residency by then.

But the expectations and the reality shocked some of his classmates at the New York College of Osteopathic Medicine. “I would never have done this if I realized how demanding it was,” some grumbled.

Today, Fox is an associate professor of surgery at Rutgers University-New Jersey Medical School and medical director at JEMSTAR, the New Jersey Emergency Medical Services Helicopter Response Program. But he never forgot his start at Binghamton University’s Harpur College of Arts and Sciences, and the regrets of his medical school peers.

In 2012, Fox kickstarted his idea by giving a talk to students on a visit to Binghamton, drawing nearly 75 on a Friday afternoon. That first talk sparked the Physician Alumni Lecture Series, which gives students the opportunity to hear from alumni physicians, residents and medical students representing a variety of specialties. Participants tackle questions ranging from how to stand out as a medical school applicant to prerequisite coursework, gap years, career paths and more.

Both questions and answers are frank and realistic. How heavy is the debt burden? Will I ever be able to have a family, or will I be at work all the time? Is becoming a doctor really worth it?

Harpur College’s alumni physicians are dedicated healers — and eager guides to Binghamton students who seek to follow in their footsteps. Many participate in the lecture series, welcome job-shadowing and mentorship opportunities, and donate generously to support Harpur College.

“I was very fortunate. I think if I wasn’t at Binghamton, maybe I wouldn’t have been so lucky,” says Dr. Camille Clare ’92, chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at SUNY Downstate Health Sciences University and a professor in the College of Medicine and School of Public Health. “It really changed my life and that’s why I am so committed to the students. I want them to be successful and give back.”

There isn’t a single path to becoming a physician, a fact that Syracuse-area cardiologist Dr. Mark Charlamb ’87 finds fascinating.

Becoming a doctor

The son of an ophthalmologist, Charlamb accompanied his father on hospital rounds while growing up, and medical conversations were a dinner table centerpiece. His own path was fairly straightforward: He majored in biological sciencesand took advantage of an early assurance admission program at SUNY Upstate Medical University, new at the time.

“My parents always told me that with a medical degree, you can do anything. That’s true today,” says Charlamb, who is also an assistant professor of medicine at SUNY Upstate.

“I tell my kids that you can really do anything you want: You can practice medicine, you can do pharmaceutical work, you can do research, you can work for an insurance company.”

His son is continuing the family tradition: He graduated from Binghamton in May and enters medical school at SUNY Upstate this fall. Charlamb’s brother and sister-in-law are also physicians.

But as he frequently points out to Binghamton students, the direct route isn’t the only one, or even the most preferable. Charlamb attended medical school alongside former musicians, nurses, a Coast Guard service member and more. Many people take gap years before entering medical school, do clinical research or even pursue other careers first.

Take Dr. Edmund Lee ’80, for example. Lee grew up in an immigrant family; his widowed mother operated a laundry downstate, and he and his siblings were the first in the family to attend college. The biochemistry major came to Binghamton intending to become a physician. His advisor, Associate Professor Frederick Kull, prompted him to reconsider.

“As a physician, you can help one person at a time, and that is good,” he told Lee. “But as a researcher, you may make a discovery that can help millions — but you may never meet those people.”

Lee went on to earn a doctorate in pharmacology and toxicology at Rutgers University and embark on a career as a cancer researcher, with fellowships at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Md., and Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Wogan Laboratory. But he hit a professional wall; to obtain grants from the National Institutes of Health, it became increasingly necessary to collaborate with a medical doctor — or become one himself.

During the day, he researched the genes behind cancer; at night, he studied for the MCAT and won admission to Harvard Medical School. Today, he is a practicing dermatologist at Mount Sinai Medical Center. His specialty intersects with his research interests: He explored the mechanism behind a treatment for psoriasis in his doctoral dissertation.

After earning his medical degree, he completed a fellowship at The Rockerfeller University, where he discovered interleukin-23, the key inflammatory cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. All of the current therapies released since 2004 are based on his discovery.

“Strive for excellence and you will have a fulfilling life. If that means a career in medicine so be it. If not, strive in another endeavor,” Lee says. “There are many ways to make your life’s work meaningful.”

College experiences can prove transformative for physicians-to-be, building on connections with professors, mentors and each other.

The Harpur connection

For Clare, that critical connection came through the Charles Drew Minority Pre-Health Society; established in 1979, it’s the oldest pre-medical organization at Binghamton. Through the group, she learned about medical school and the application process, and attended conferences.

A neuroscience major and the daughter of immigrants from Jamaica, Clare became interested in medicine through her mother, who worked as a laboratory technologist at a Bronx hospital. At Binghamton, students and graduates in the Drew Society shared tips for success with one another, and almost all went on to attend medical school, she says.

“The pre-med curriculum is rigorous and very tough. Just being with others who were like-minded and very committed to pursuing medicine definitely changed my life,” says Clare, who served as the Drew Society’s alumni advisor for 12 years until 2019.

For Fox and Dr. Nisha Gandhi ’93, that formative influence came through Harpur’s Ferry, the student-run volunteer ambulance corps on campus. Neither took the traditional path to medicine: Gandhi was a mathematical sciences major who planned to become an actuary, and Fox majored in political science, even though he had intended to become a doctor since earning his first Boy Scout merit badge.

“I came into school with this concept that I was going to get as much information as I could out of my education about the world, as opposed to just being narrowly focused on medicine,” he says. “Binghamton gave me the opportunity to be broad-based.”

Both spent long hours in Harpur’s Ferry, and discovered a passion for trauma and critical care, high-intensity fields that require thinking on your feet and coming to quick decisions. One example: On a recent day, Fox, a trauma surgeon, saved the life of a man with multiple gunshot wounds during an eight-hour operation. It’s not for everyone, he admits.

Fox remains involved in Harpur’s Ferry to this day; he gives lectures to the ambulance corps during his Binghamton visits, and helps them review patient encounters. A recipient of the Edward Weisband Distinguished Alumnus/a Award for Public Service or Contribution to Public Affairs, he was instrumental in bringing “Stop the Bleed” to Binghamton; it’s a nationwide campaign that trains people to control bleeding in injured patients while they wait for medical care to arrive.

Now director of the medical surgical intensive care unit at Englewood Hospital in New Jersey, Gandhi also felt drawn to work with the most acute cases — a part of the medical field far different from her mother’s career in pediatrics. During her junior year, she dramatically shifted her life plan, taking pre-medical courses in addition to her math coursework, and took a gap year to prepare for medical school. Harpur’s flexible liberal arts curriculum allowed her to pivot, she said.

“There are so many opportunities that we have to shape our future, and just because you’ve chosen one path doesn’t mean that you’re stuck with it,” she reflects. “You have the opportunity to change your path, your experiences and your journey at any point in time.”

Giving back

The heart of medicine beats with the desire to give back — to patients in need and also to the larger world.

“I went to medical school so I could serve my community,” says Clare, who has sought to address inequities and healthcare disparities in underserved communities throughout her career.

That is true in a literal sense: She attended the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, a short distance away from where she grew up. She spent two decades working at New York City Health + Hospitals/Metropolitan, serving underserved New York City communities, and also served as the associate dean of diversity and inclusion for New York Medical College, where she explored ways to draw more Black and brown students to medical careers.

During the coronavirus pandemic, physicians served the public good in many ways. They guided residents and medical students, some of whom entered the field early to aid in the global crisis. And they hit the frontlines themselves, and not only at their own hospitals.

During the height of the pandemic, hospitals were full and even surgeons pitched in to treat failing patients. And yet, they were empty, too, of the usual crowd of family members and visitors, unable to bid farewell to the dying.

As a critical care doctor, Gandhi is no stranger to death, but the cases she saw during the pandemic were staggering. In a scene reminiscent of a Hollywood disaster film, her hospital held brainstorming sessions during the pandemic’s early days to figure how to prepare for a surge of cases. Because COVID-19 was a novel virus, they didn’t have established plans for treatment.

“We didn’t know how to treat this viral infection, and it wasn’t behaving like other viral infections,” she says. “We had to figure out what we were seeing and adjust. What we did in March and April was completely different than what we did in June, July and August.”

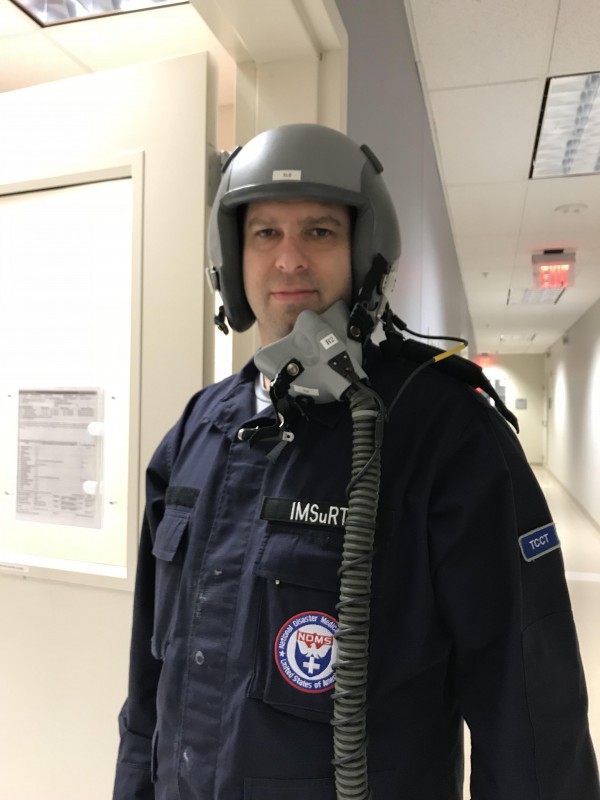

Fox lends a hand at crisis situations across the country as part of the National Disaster Medical System, a federally coordinated service under the Department of Health and Human Services. A member of their critical trauma care team, he has aided in air medical evacuations, natural disaster response and more around the country.

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, the air medical team evaluated Americans returning from China and from cruise ships, transporting them to military bases where they could be quarantined and receive medical care. Some days, they worked a full 24 hours on an aircraft, clad head to toe in protective gear, he remembers.

He also went to hospitals around the country to provide critical care as the pandemic surged, from southern California to Montana. In January, the team was deployed to provide medical care, if needed, at the presidential inauguration in Washington, D.C.

Serving on the frontlines of medicine during the pandemic was unimaginably difficult, physicians say, but it also reaffirmed their love for the field and their sense of mission. The pandemic also has sparked more interest in medicine, a phenomenon called “the Fauci effect,” referring to Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Anthony Fauci. At Upstate, applications are up 25%, Charlamb says.

“The people applying today are driven,” he says. “Their credentials are great, their stories are great and their personalities are great. It’s nice to see.”

Even during the pandemic, Harpur alumni physicians generously shared their time with Binghamton students. The alumni lecture series and the Current Issues in Medical Practice Winter Session course continued via the Zoom online platform.

Many physicians — Clare and Lee among them — also mentor students, and offer them opportunities to job-shadow or conduct research. This guidance can open doors: Of the nine students Lee has mentored through the years, for example, eight of them have since been admitted into medical, dental or physician assistant programs. (The ninth is taking a gap year, which is common prior to medical school.)

When he speaks to Binghamton students, Charlamb has a core message: Have a dream, build on that dream and complete it, no matter which road takes you there. When it comes to choosing a specialty, consider your happiness and satisfaction rather than the paycheck; after all, this will be your long-term career.

“I love giving back. Binghamton was great to me and [SUNY] Upstate was great to me,” he says. “If I have the opportunity to give back, I’m all for it.”