Trip around the World: The Translation, Research and Instruction Program celebrates its 50th anniversary

Through language, we understand the world.

We transmit our knowledge — the scientific and the subjective, the ordinary and the sublime — through a medium of verbs and nouns, adjectives and participles. Through language, we share artistic creations, observations and emotions, crossing the divide that separates one human mind from another.

Translation is a skill as complex as it is necessary: Languages, after all, don’t express the same ideas in the same ways. But it’s more than a tool; it’s also a subject worthy of study in its own right.

Since its founding in 1971 by the late Distinguished Service Professor Marilyn Gaddis Rose, Binghamton University’s Translation Research and Instruction Program (TRIP) has built a truly global reputation. Graduates around the world recommend the program to their own students, passing on TRIP’s legacy to a new generation of scholars.

One of its hallmarks is the PhD program in translation studies, the first of its kind in the United States. It also offers a graduate certificate and an undergraduate minor, and a master’s degree is under development.

Translation skills are increasingly in demand from a wide range of employers, ranging from nongovernmental organizations to immigrant services and international trade, says Associate Professor of Asian and Asian American Studies Chenqing Song, the program’s director since 2017.

TRIP has a proud history at Binghamton, and its doctoral program was developed even before there was an appreciation for the critical importance of translation studies, says Harpur College Dean Celia Klin. In addition to Gaddis Rose’s legacy and the continued development of TRIP’s degree programs, she pointed to exciting interdisciplinary initiatives such as the Ladino Lab.

“In our increasingly global world, translation studies are a critical part of a liberal arts college and Harpur College is proud to be celebrating the 50th anniversary of TRIP,” Klin says.

TRIP began as a program within the Department of Comparative Literature, where it is still housed today. Its focus is two-fold: helping translators hone their skills and emphasizing translation theory, says Distinguished Teaching Professor of Philosophy Anthony Preus, who was recruited by Gaddis Rose.

Translation theory

“Marilyn Gaddis Rose wanted to give an opportunity to develop trained translators for actual careers,” Preus says. “She also established a service to link people who needed translation done with people who could do it.”

That was the Translation Referral Service (TRS), where graduate students tackled a wide range of projects in the days before widespread internet use reduced the need for localized translation services. The service, which ended in 2009, helped open doors for many translators to connect with organizations and publishers and begin working in the field, says Kim Allen Gleed, MA ’97, PhD ’05, now an English and French professor at Harrisburg Area Community College in Pennsylvania.

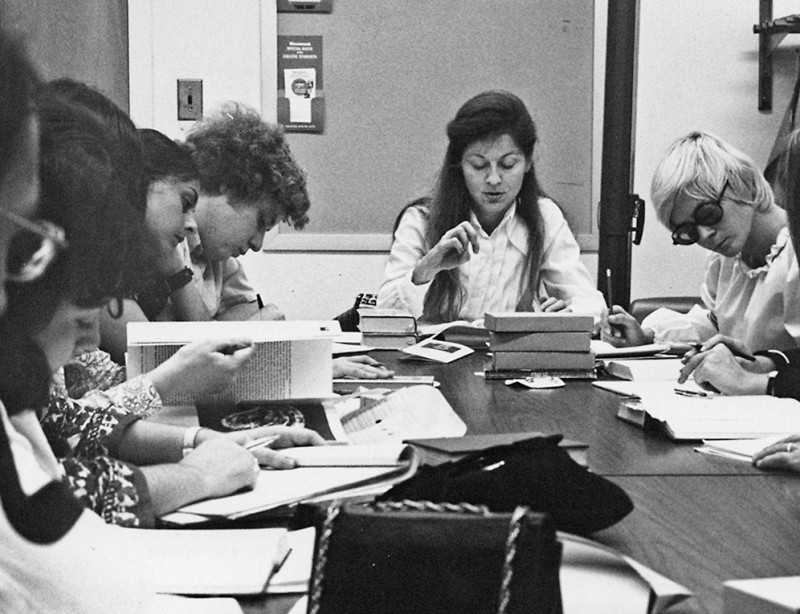

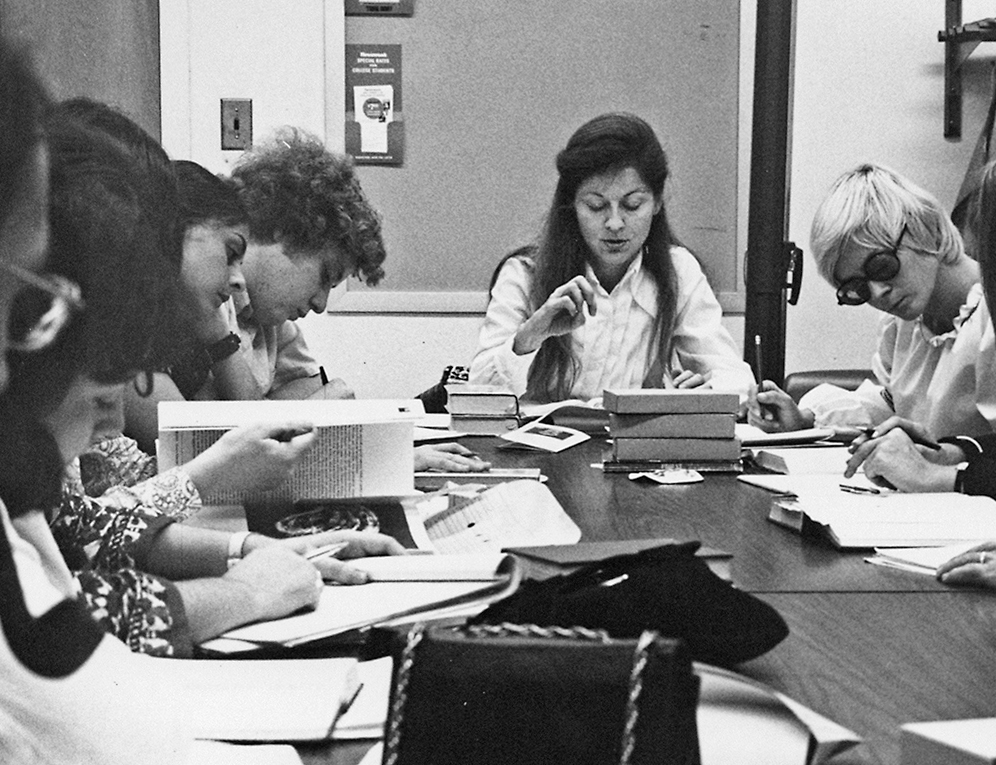

In addition to the TRS, Gaddis Rose also spearheaded the grant-funded Center for Research in Translation (CRIT) and coordinated translation workshops in which professors worked with students specializing in particular languages, says Ithaca College Associate Professor of Italian Marella Feltrin-Morris, who earned doctorates in both comparative literature (’05) and translation studies (’08) at Binghamton.

What truly set TRIP apart was its doctoral program in translation studies, unique among American universities when it began in 2004; Feltrin-Morris was the first to receive a doctorate through the program. Translators don’t need a doctorate to work in the field, but the advanced degree opens up additional career possibilities in research and teaching, notes Marko Miletich, an assistant professor of Spanish and translation at Buffalo State College who earned his PhD at Binghamton in 2012.

Gleed, who earned her master’s and doctoral degrees in comparative literature, considers the program the perfect blend of translation theory and practice.

“We studied the roots of translation, going all the way back to Saint Jerome, and moved through to modern and contemporary theorists, many of whom Professor Gaddis Rose knew and invited to campus as guest speakers and lecturers,” she says. “The study of the discipline informed our practice, and as translators, we worked with a multitude of texts, from literary to technical and everything in between as we developed and honed our skills.”

A pioneer in the field of translation, Gaddis Rose shaped the program in myriad ways. She recruited people into TRIP; among them was Preus, who has published translations from both French and classical Greek. She also advocated for her students and sought to broaden their horizons in multiple ways.

A pioneering founder

“I remember Marilyn Gaddis Rose’s calm, steady, yet unwavering, energy. She was an incredibly intelligent and strong woman, so devoted to our field and to the success of her students,” says José Dávila-Montes, one of the visiting scholars who came to TRIP while conducting research.

He had only intended to stay in Binghamton for nine months while he worked on doctoral research for his alma mater: Autonomous University of Barcelona in Spain. Nine months became 18 as Dávila-Montes stayed on to complete a master’s degree in Spanish literature at Binghamton and see his second son born. Today, he is a professor of translation and interpreting at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, where he founded one of the first bachelor’s programs in translation and interpreting in the country.

He has many cherished memories of Gaddis Rose, such as the time in 2004 when she took a half dozen graduate students in a van to the second American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association conference in Amherst, Mass. Today, ATISA is a national reference for the discipline, Dávila-Montes says.

When he held a party at his home, Gaddis Rose came, along with TRIP graduate students from around the world.

“I am so grateful that I could witness those moments. Many of my current colleagues and friends in the field, I met them there first,” he says. “Long-lasting friendships and academic collaboration were built around Marilyn’s amazing personality.”

Gleed’s favorite memory of Gaddis Rose also involved a road trip; when she presented at a James Joyce conference at Cornell University, her mentor accompanied her each day to cheer her on as a new academic. Conferences also spark Feltrin-Morris’ memories of Gaddis Rose, in particular in those moments when ideas seem to emerge spontaneously.

“Among the many lessons that I learned from her is this: ‘The best ideas come when you’re doing something else. And it’s true!” she says.

Feltrin-Morris and TRIP alumnae María Constanza Guzmán and Deborah Folaron published Translation and Literary Studies: Homage to Marilyn Gaddis Rose three years before their mentor’s death in 2015. Feltrin-Morris interviewed the professor for the volume, and the co-editors solicited articles from her former students.

Gaddis Rose not only gave her blessing but also actively participated, contributing a new essay on the stereoscopic reading of Jane Austen through translations of her work.

“We wanted to do a Festschrift to honor Marilyn Gaddis Rose because she created something quite amazing and quite unique at the time,” Feltrin-Morris says. “She was a force of nature; she had her hands in so many fields. She had to because of the nature of translation studies.”

Translators can be found throughout University departments, working within their own disciplines. Because of this, TRIP has deep connections to many other departments in Harpur College.

An interdisciplinary field

“We have students coming from around the world. All share one passion, which is translation, but they approach translation very differently,” Song says. “Some want to do it under, say, sociology. For some, it’s more linguistic than literary. We also have students who are interested in political science, or gender studies or theater, music, you name it!”

Today, TRIP has 38 doctoral candidates, the majority of them international students; only a handful are domestic students. Many graduates return to their home countries to teach. The most common languages for translation include Arabic, Chinese, Korean, the Romance languages and occasionally German, but students also translate other languages, Song says.

The program has changed through the years to accommodate students’ interests and needs. Doctoral dissertations, for example, are no longer limited to theory-based analysis and can now include translation.

“This really addressed what many of our students wanted to do and what they felt was important to secure good positions in the future,” says Professor of Korean Studies Michael Pettid, who headed TRIP from 2011 to 2016.

The regions from which its students come also have shifted. More than a decade ago, TRIP began drawing more students from the Middle East, thanks to generous government programs and grants from the region such as the Saudi Arabian Cultural Mission. These students are typically teachers in their home countries, where a PhD in the field is unavailable, Song says.

Under Pettid’s leadership, TRIP began a dual degree PhD program with Beijing International Studies University; Chinese students from BISU, funded by a government grant, finish their doctoral degrees in Binghamton.

TRIP graduate students are a significant force in campus life, running an academic conference every three years, holding multiple events and supporting multiculturalism and gender and racial equity initiatives, Song says. Irem Ayan, who earned her PhD through TRIP in 2019, compares the program to a mini United Nations. She should know; she has worked at the U.N. as a freelance interpreter.

Tarek Shamma earned a certificate in Arabic/ English translation through TRIP while finishing his master’s in comparative literature. After earning his PhD in 2006, his career took him to universities throughout the Middle East; he returned to Binghamton in 2018 as an associate professor in both TRIP and comparative literature.

“Translation is one of the most enriching fields to study on the academic and personal levels. It is highly interdisciplinary in nature, so you can pursue practically any interest that you have,” he says, noting options in the hard sciences, social sciences and the humanities. “The experience of learning other languages and cultures is one of the most rewarding I know, and one of the most useful in today’s world in practically any professional field.”