$2.4 million NIH grant to fund research into better, faster diagnosis of lung nodules

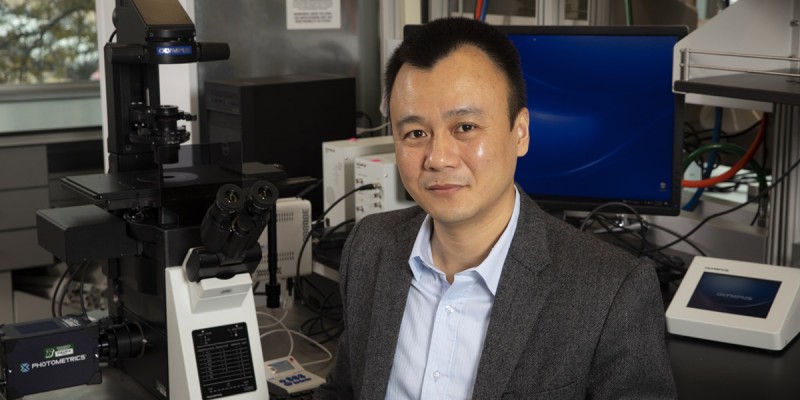

Assistant Professor Yuan Wan's funding is through the NIH’s prestigious MERIT Award program.

More than 1.5 million Americans are diagnosed each year with solitary pulmonary nodules (SPNs). These abnormalities in the lungs, often found during routine X-rays or CT scans, are isolated groups of cells up to 3 centimeters in size.

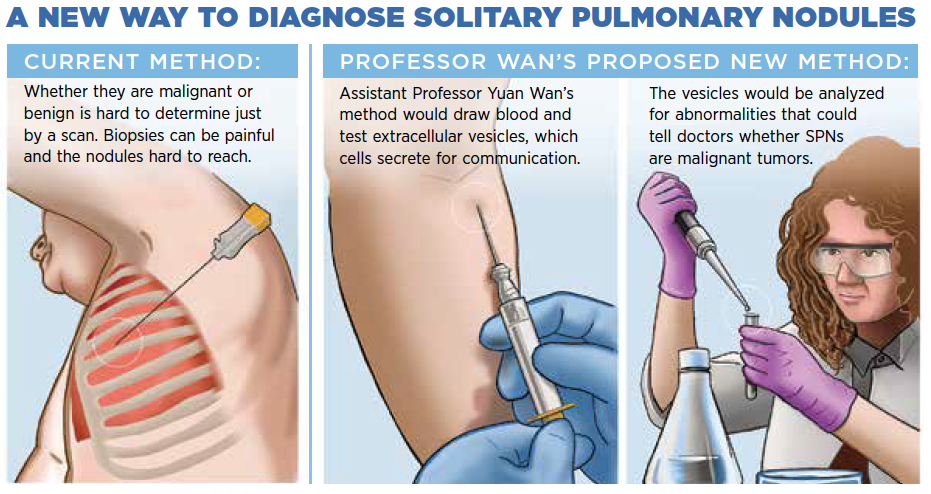

Many SPNs are benign, but figuring out which ones are malignant isn’t an easy process. One method is to scan patients again in three to six months so that the nodules can be rechecked. If it looks like they’ve grown or changed, there’s a risk that it could be a malignant lesion and cancer cells already are traveling through the bloodstream to other parts of the body.

Another method is do tissue biopsies, but those can be painful and difficult to accomplish, because the nodules are relatively tiny. Missing the target and taking surrounding healthy cells instead can lead to misdiagnosis.

Assistant Professor Yuan Wan wants to develop a faster, less painful way to diagnose malignant SPNs. The Department of Biomedical Engineering faculty member at Binghamton University’s Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science received a five-year, $2.4 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, with the possibility of two years’ additional funding pending initial results.

The funding is through the NIH’s prestigious MERIT (Method to Extend Research in Time) Award program. Established in 1986 and also known as an R37 award, the MERIT program supports both experienced researchers as well as early-stage investigators such as Wan who are in the first 10 years of their careers.

Wan hopes to reduce detection time so that patients would know within a week about whether their SPNs should be removed. The method would analyze extracellular vesicles, which are small sacks of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids that cells secrete for intercellular communication.

Under Wan’s vision, a patient would give blood, and the vesicles would be extracted from the plasma and enriched using specially designed microfluidic devices.

“If we can collect these vesicles and use a very high-sensitivity detection technology,” he said, “we probably can tell if there is some abnormal information from the extracellular vesicles and give a diagnosis about whether it’s a tumor or just benign based on the mutation information.”

In a collaboration with Johns Hopkins University, the effectiveness of these new tests would be judged against tissue samples collected from patients with SPNs.

“In cancer diagnosis right now, tissue samples are still the gold standard, so when you develop any new technology, you always need to compare with the tissue sample,” Wan said. “In this experiment, we’re going to collect the samples from malignant SPN patients as well as normal tissue samples and benign SPN samples as negative controls. We will extract the DNA from the tumor sample and the normal sample, and then use a 565-gene panel to learn about mutation evolution in cancer progression, look at the mutation pattern and find out the mutation hallmarks of malignant SPNs.”

From there, Wan would zero in on 60 or fewer gene mutations that are telltale signs of malignancy and develop a commercial version of the test for use by medical providers.

His ambition is also to help doctors better analyze CT scans of malignant nodules using machine learning instead of relying on their own eyes.

“In a pilot study, we collected 3,000 images and trained the program to tell the difference between potentially cancerous ones and benign ones,” he said. “Eventually, we would expand the sample size to train the program to improve the diagnosis with sensitivity and specificity. In the future, once a red flag is raised by the intelligent program, doctors will suggest that patients take the extracellular vesicles-based test for further diagnosis.”

Before earning his PhD in biomedical engineering from the University of Texas at Arlington, Wan graduated from medical school in China, but he found the pace it required to be daunting.

“In China, being a doctor is not an easy job,” he said. “In one morning, a doctor can see probably 20 to 30 patients — it is super-busy. So that’s why after graduation I went into biomedical engineering.”

Having that medical training does give him better insight into patients’ needs, and developing a less painful method for assessing SPNs and potentially other types of cancer offers a more compassionate form of care.

He also stressed the importance of detection: “If doctors identify nodules as malignant early enough and they remove the lung section, patients have a five-year overall survival rate of more than 95%, possibly even reaching 100%.”

Wan’s grant for “Liquid biopsy of solitary pulmonary nodule with extracellular vesicles” is NIH #1R37CA255948-01A1.