Mechanisms of addiction: Psychology assistant professor receives NIH grant for brain research

It’s one of those running jokes in science about how discoveries get made: First, researchers sit down in a café somewhere, and then they chart their master plan on a paper napkin.

That’s exactly how Binghamton University Assistant Professor of Psychology Anushree Karkhanis’ collaboration with Drexel University Associate Professor Jessica Barson began. This summer, they received a five-year, $2.59 million grant from the National Institutes of Health for their project: “Mechanisms of rostrocaudal differences in accumbal kappa opioid receptor effects on ethanol drinking.”

“This project allows us to look at specific neuron populations and how this particular receptor that we’re studying modulates two different populations of neurons within an area of the brain,” Karkhanis said.

Karkhanis first began researching the up-regulation of accumbal kappa opioid receptors during a post-doctorate fellowship at the Wake Forest School of Medicine. Many labs in the United States, including her own, have shown that this receptor is upregulated, meaning that it increases its function after alcohol exposure at various ages.

Initially implicated in addiction processing in animal models, recent studies have shown that opioid receptors have solid connections to addiction in human populations, too. For example, the drug naltrexone — most commonly associated with treating opioid overdoses, but also used to combat alcohol use disorder — blocks all of the opioid receptors in the brain.

The research project centers on the rostral (anterior) and caudal (posterior) sub-regions of the shell of the nucleus accumbens, which is involved in emotion- and reinforcement-related processing. The hypothesis is that the two sub-regions of the shell respond very differently to pharmacological manipulations of the kappa opioid receptor and alcohol use.

The brain rewards behavior with dopamine, but the organic chemical doesn’t play the game alone; every neurotransmitter system is involved to some extent. Karkhanis’ research targets the serotonin system, which is involved in mood, emotions and stress, along with dopamine. Researchers believe that kappa opioid receptors modulate both of these neurotransmitter systems, but they don’t yet know the mechanism and whether each system is regulated differently.

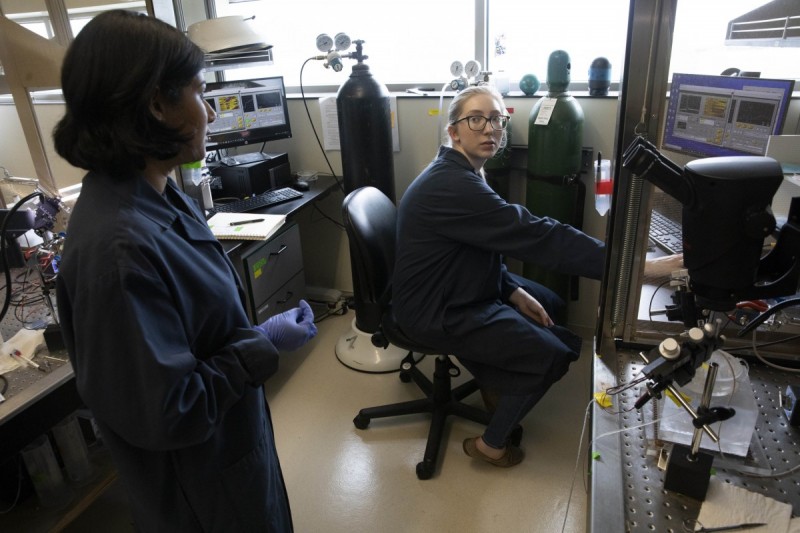

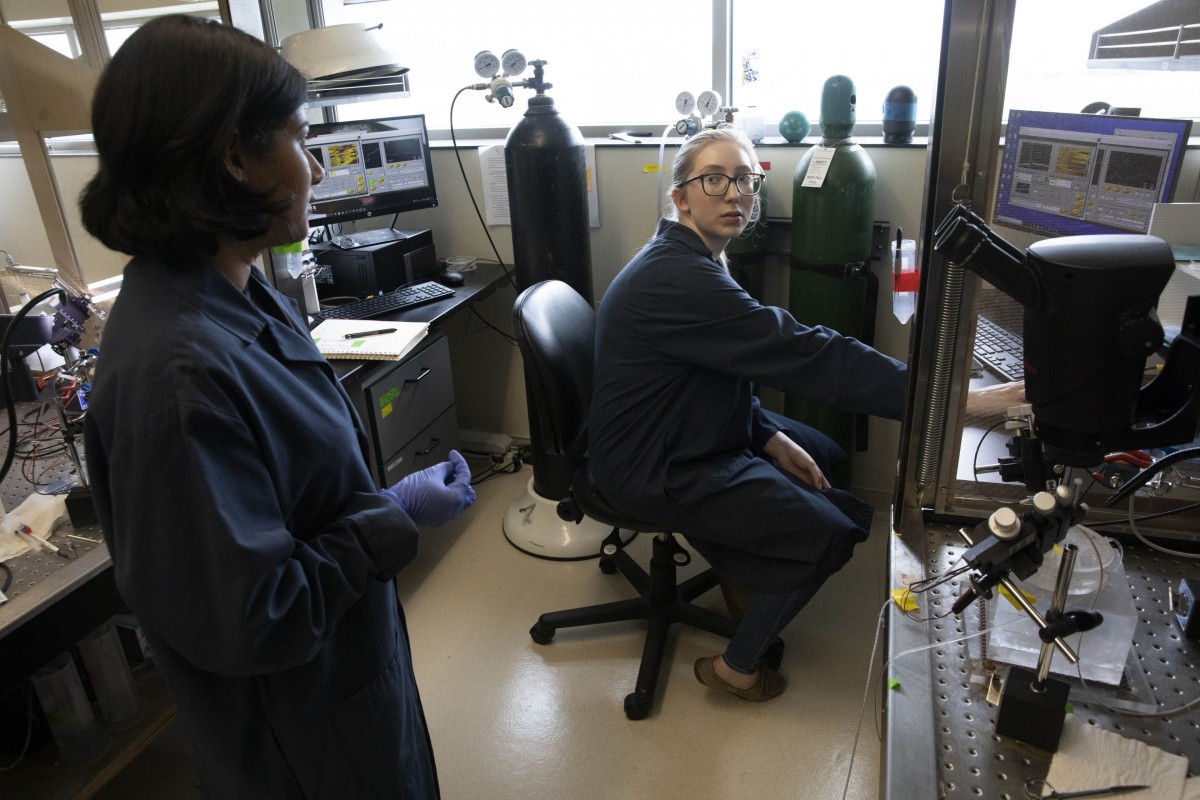

In this five-year project, Karkhanis and Barson hope to answer this question, and to see how the modulation of neurotransmitter systems changes when an organism is exposed to alcohol. They will use rats in their research, and a combination of micro-injections and viral technologies to manipulate specific neuron populations. Karkhanis’ lab also uses fast-scan cyclic voltammetry, an electroanalytical method, to measure the release of neurotransmitters.

The idea behind the project sparked at a conference, where Barson had invited Karkhanis to speak at a panel; in her talk, the latter touched upon rostro-caudal differences in dopamine transmission following kappa opioid receptor activation. Afterward, they chatted over coffee about the data that Barson was seeing in her lab after one of her students saw opposing effects after conducting microinjections activating kappa opioid receptors along the rostro-caudal axis in the nucleus accumbens. Barson’s data worked well with the data produced by Karkhanis.

“We literally charted a plan on a paper napkin, which is a kind of running joke in science about how science ideas are conceived,” Karkhanis remembered.

Long-term, this research could improve treatment options for individuals suffering from alcohol use disorder. While naltrexone is effective, it also carries multiple side effects and many patients don’t follow through with the treatment. Research may discover ways to reduce the dosage of naltrexone, or find other medicines that could target treatment.

“This grant actually gives my lab an opportunity to go in a very new direction like serotonin detection; the technique that I use in my lab is not very common,” Karkhanis said. “It connects my lab with a very new area, highlighting serotonin’s role in alcohol use disorder.”