After two decades, Watson College’s Roy McGrann retires from mechanical engineering faculty

McGrann was director of Engineering Design Division and co-founder of sustainability engineering minor

For the first time in 20 years, the fall semester started at Binghamton University without Professor Roy McGrann.

As a faculty member in the Department of Mechanical Engineering for the Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science, McGrann taught, mentored and befriended hundreds of students over the years. In the first few months of retirement, he already misses the classroom.

“I love the influence that teachers can have on students,” he said. “I thought my educational experience was very worthwhile, and I wanted to transmit that to younger generations.”

For many Watson alumni, McGrann is best known as director of the first-year Engineering Design Division program (2004-08) and as the co-founder and co-director of the college’s minor in sustainability engineering. The sustainability minor started in 2010 after students asked for curricula focused on clean energy and environmentally friendly topics in the face of climate change.

“A large part of it was student pressure on us, and our recognition that we needed to set up this program,” he said. “We had three core courses that we originally set up, and then we made everything else electives. Those three courses are now taught in the Engineering Design Division.”

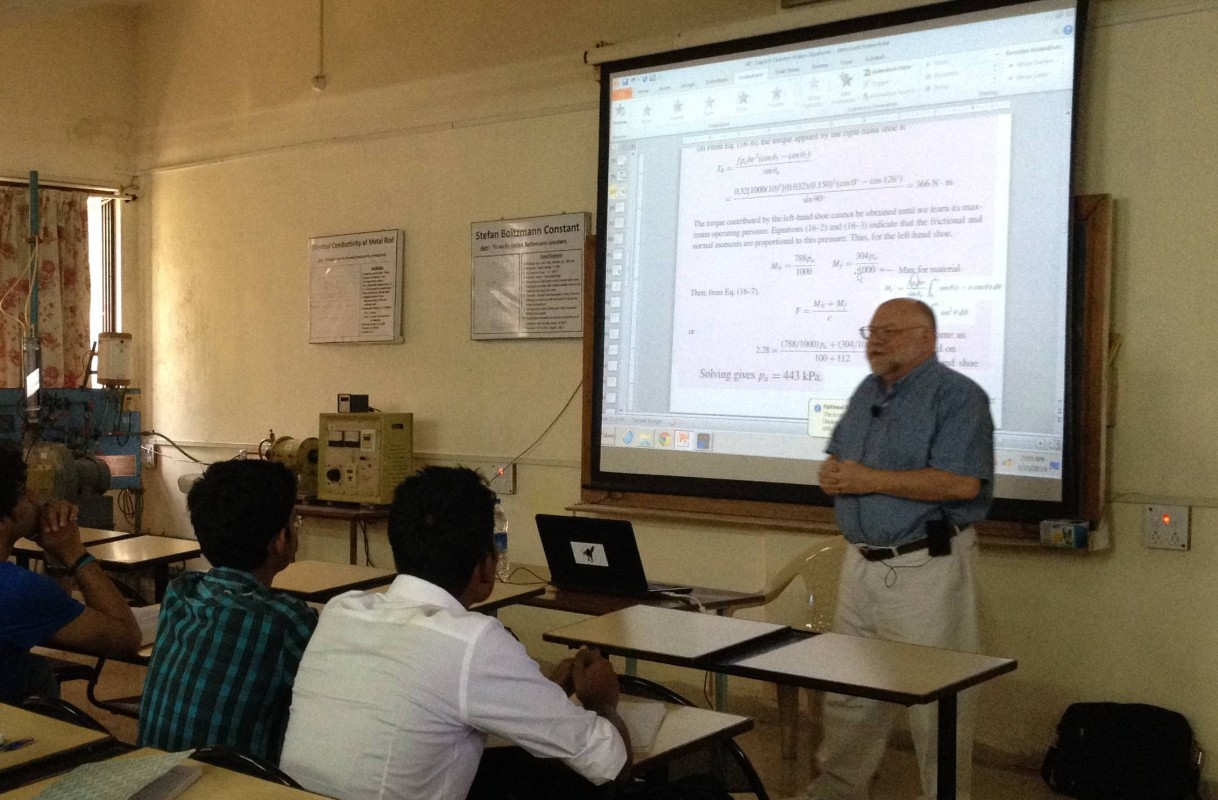

During his tenure, McGrann also taught a computer-aided engineering course in the fall with a more “traditional” mechanical engineering design course follow-up in the spring.

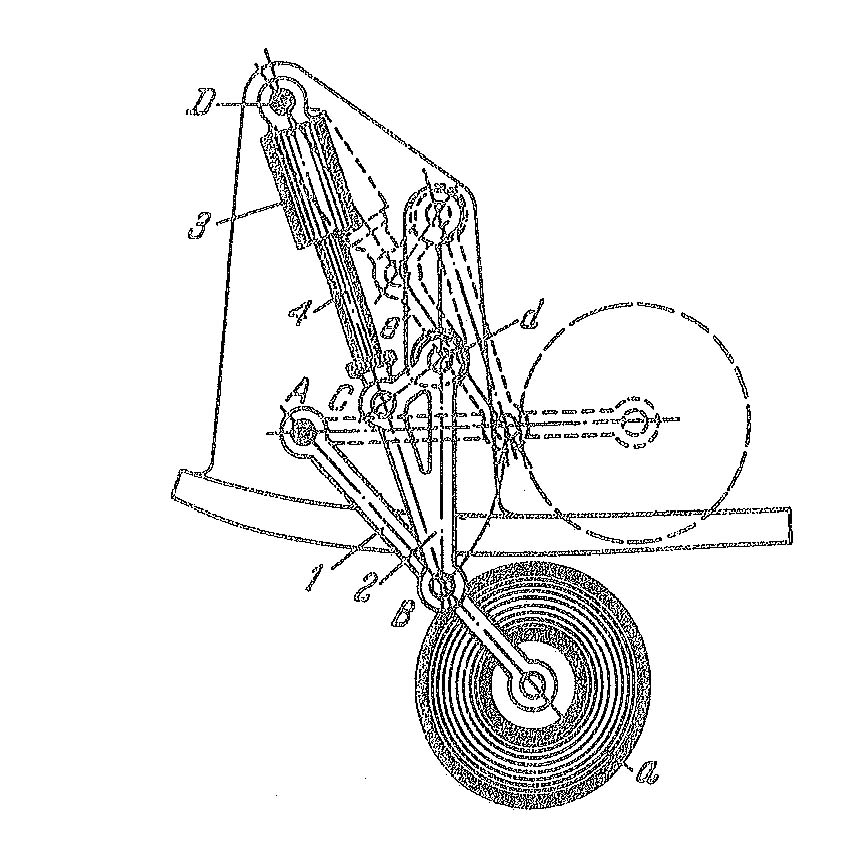

“The way I taught ME Design, students had to do a complete design,” he said. “They had to come up with a problem that had a mechanical engineering solution, then figure out and design, down to the detailed drawings and specifications, a solution to that problem.

“They met with me individually twice a semester — the first meeting was 15 minutes and you had to explain your problem to me, then the second one was up to 30 minutes and we’d go over your drawings and I was going to mark them up. It wasn’t a problem when there were only 40 students in the class, but when there were 120 students, that was 240 meetings!”

The most impressive students over McGrann’s years at Watson were the ones excited to come up with new solutions to real-world problems. Once, he mentioned that it would be nice to have a cheap little robot to teach about lessons about controls, and the next day one standout student came in with a robot made out of old CDs and a motherboard — a device that later resulted in a successful PhD thesis. Another time, a student (who now works at Ford Motor Company) built a complete CAD model of a gas turbine engine overnight.

“There were two types of students in the design course,” McGrann said. “One type was ‘OK, I’ve got to get through this. This is just a required course.’ Then there were the students who said, ‘Oh my God, finally I get to do something I want. I get to work on a problem that I’ve thought about for years.’”

Before coming to Binghamton, McGrann earned a liberal arts degree at Brown University and thought he would teach philosophy. That didn’t pan out, though, so he went to work in manufacturing as a machine operator. He realized that supervisors with engineering degrees earned more and decided to pursue a BS in mechanical engineering at the University of Tulsa.

“I worked for another 10 years as an engineering manager after the bachelor’s degree, and then the company I worked for was sold,” he said. “I thought, ‘OK, this is a good time to go finish the PhD.’ I went back to my advisor [from the University of Tulsa] and said, ‘Hey, remember me?’ Fortunately, they did.”

Although he studied mechanical metallurgy for his PhD, he switched to engineering education research after arriving at Binghamton, meaning his “lab” was the classroom. In 2008, he earned a SUNY Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Teaching.

He credits the influence of former Watson colleague Richard Culver for the new direction — and as you’d expect from someone interested in philosophy, he has some thoughts about how the role of engineering fits into the larger society.

“There is the dichotomy between those who think that engineering is more like physics or a science and those who think engineering is more like sociology — that it’s a social practice and you need to develop in students the responsibility for what you’re doing,” he said. “I’m obviously on the ‘develop the responsibility’ side.”

He also has some ideas about his own discipline: “A good mechanical engineer has the ability to see a problem, to find a way it can be solved and then to know the nitty-gritty details.”

Since his retirement, McGrann has moved to Colorado and is enjoying his new life there. He will keep his hand in the engineering world as an evaluator for the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET), which accredits post-secondary education programs in applied and natural science, computing, engineering and engineering technology. He would like to become more involved in Engineers Without Borders, which uses the technological skills of its members to foster projects in developing countries.

He also keeps in touch with many of his students, celebrating their achievements and even attending some of their weddings.

“Over the years, I had some exceptional grad and undergrad students who have gone on to do great things. When they go out into the world and accomplish so much, I just think, ‘OK, you paid attention!’” he said with a laugh.