Unraveling a mystery: Research explores longevity and ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) has a devastating trajectory, first manifesting as muscle weakness and slurred speech. From there, it steals progressively more motor function until sufferers are no longer able to breathe on their own. There is no cure, and treatments can only prolong the inevitable by months, at most.

Most patients die within two to five years, although there are exceptions: theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking famously lived more than 50 years with the disease. Another striking case: The Indigenous population of Guam in the years after World War II, which developed ALS in very high numbers for unknown reasons.

Unlike typical ALS patients, many Guamanians with the disease lived a long time without medical intervention — 20 years or more. Reports indicate the more severe the symptoms at onset in the Guamanians, the longer they lived — the opposite of modern patients.

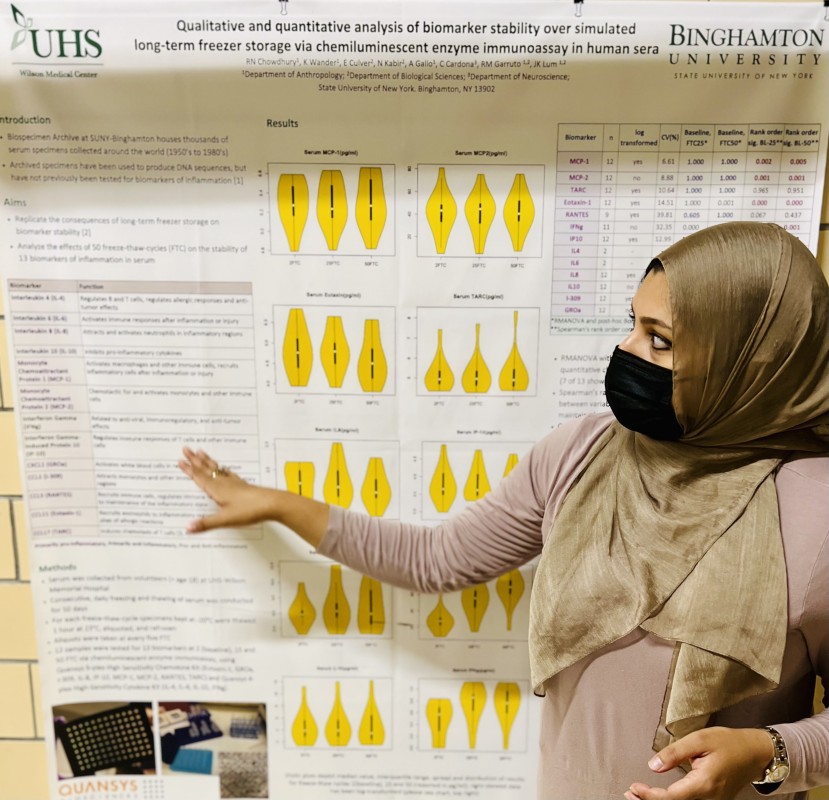

Risana Chowdhury, a doctoral candidate in anthropology, is looking to discover why.

To that end, she is looking at a panel of immunoregulators in human serum from Guam that is part of Binghamton University’s biospecimen archive, under the direction of Chowdury’s mentor, Professor Ralph Garruto. Her focus is on c-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammation produced by the liver, and cytokines, which regulate immune function. As with most diseases, elevated levels of inflammation are part of ALS.

“I am interested in how serum inflammation may have been different in Guamanian ALS patients compared to modern ALS patients, and how these differences may have influenced the unusually long lifespan seen in some cases of Guamanian ALS,” she said.

A fascinating field

Born in Bangladesh, Chowdhury moved to the United States at the age of five; she grew up mostly in Missouri. Originally contemplating a career in dentistry, she came to Binghamton with her husband — a resident in internal medicine at the time — and decided to pursue a master’s degree in biomedical anthropology. The field proved so interesting that she shifted gears during her master’s program and decided to become an anthropologist herself.

“I think biological anthropology is fascinating because it is the study of humans interacting with their environments. It observes how one affects the other and how human behaviors, on both individual and community levels, affect health outcomes,” she said.

She completed her MS in 2009 and enrolled in the MA/PhD program in 2015, completing her MA in 2018. Life has been busy in other ways, too; she had three children during the course of her studies at Binghamton.

She has found the University to be a welcoming and supportive environment, from her professors and department staff to the undergraduate students who have assisted her research through the years; many of the latter have gone on to their own graduate programs or to medical school. Chowdhury’s research also received a boost from internal grants, including one from Harpur Edge.

“My female and BIPOC (Black, indigenous and people of color) professors have also inspired me. I know it sounds cliché, but representation matters!” she said.

Her advisor, Associate Professor Katherine Wander, helped Chowdhury formulate hypotheses for the project. The central premise is this: Because humans have co-evolved with parasites and infectious diseases, our ancestors’ immune systems learned to self-regulate based on these interactions. Intestinal parasites, for example, down-regulate the host’s immune response in order to survive. Higher-income countries have significantly reduced childhood exposure to such pathogens, which can result in a hyperactive immune system — in turn leading to an increased risk for developing allergies and autoimmune diseases later in life.

ALS’ emergence on Guam is a mystery; when the Spanish ruled the island from the mid-1500s to 1898, they made no note of it. The incidence of ALS has also decreased since the modernization of the Pacific Island, with the last remaining cases — affecting between 10 and 25 individuals — occurring between 1980 and 1991.

“According to reports, the environment of post-World War II Guam was higher in parasitic and other infectious diseases. My question is: Did Guamanians with ALS live longer because their exposure to a higher-infectious disease environment made their immune systems stronger?” Chowdhury said. “Studying patterns of inflammation in Guamanian sera of ALS cases and non-cases may help us answer that question.”

So far, she has uncovered surprising patterns in the data that support the findings of researchers from the 1950s, although it’s too early to come to meaningful conclusions.

“In the Guamanian ALS cases, elevated serum levels of some pro-inflammatory cytokines appear to be associated with longer lifespan. This is different from modern ALS cases, where higher serum inflammation is associated with shorter lifespan,” she said.

Chowdhury is currently in the process of writing her dissertation, which she plans to defend in May 2022. She hopes to continue teaching or conducting research in the field.

“We’ve lost several giants in anthropology these last few years, including our own Professor Gary James in 2020 and well as E.O. Wilson and Richard Leakey more recently. Those are enormous shoes to fill, but it would be incredible to carry on their legacy, while taking anthropology to broader and more inclusive horizons,” she said.