The Tubman Center’s road to justice and reconciliation

Center addresses structural inequities on campus and beyond

We first learn about Harriet Tubman in elementary school: an extraordinary woman who escaped slavery only to return, again and again, to lead others to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

But this great soul was also part of a complex tapestry of abolitionists, challenging the unjust laws and social structures of their day to create a society free from the stain of human bondage. Some achieved prominence in the history books, but many others toiled in relative obscurity, focused solely on the work of justice and liberation.

The collaborative effort to create lasting change is the heart of Binghamton University’s Harriet Tubman Center for Freedom and Equity, directed by History Professor Anne Bailey and Associate Director Sharon Bryant, also the associate dean of diversity, equity and inclusion for Decker College of Nursing and Health Sciences.

“People like Harriet Tubman did amazing work bringing people to freedom from the South to this area and other areas in the North. But she also worked with a group of abolitionists, and that was a multicultural group, both Black and white. It wasn’t a one-woman show,” Bailey says. “In many ways, that’s what we’re doing: We’re trying to empower others to be co-conductors with us. We’re saying, ‘Join the effort in any way you can.’”

The center opened in 2019 — the 400th anniversary of the consistent presence of people of African descent in North America, and the start of race-based slavery in what became the United States. The center’s fundamental mission is to advance justice and equity across multiple dimensions, particularly in history, educational access and success, and in medicine and science, technology, engineering and math (STEM).

“Over the past couple of years, many more people have become aware of rampant inequity in American society, and tensions across the political spectrum run high. The Tubman Center is vital in providing a forum for the issues of the day to be discussed and deliberated about,” says Dean of Libraries Curtis Kendrick, who serves on the center’s advisory committee.

The center is dedicated to honoring not only the contributions of people of African descent, but Black, indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) more generally. Despite the obstacles posed by the pandemic, its work has continued apace, with a springtime speaker series offered through Zoom. In September 2021, the center opened its physical office in Academic B; more than 200 people attended a grand opening ceremony outdoors, with small, socially distanced tours inside the new space.

While the Black Lives Matter movement has sparked interest in matters of racial equity nationwide, Bryant and Bailey describe the Tubman Center’s work as proactive and long-term, rather than in reaction to current events. Consistent advocacy on issues related to equity is critical, they say.

Kimberly Jaussi, an associate professor of organizational behavior and leadership in the School of Management, was eager to become involved in the center’s work since its start, inspired by Bailey and Bryant’s vision and its transformative potential. She is currently a member of its advisory board and also served as an ambassador for the center’s Truth and Reconciliation initiative, encouraging members of the Dickinson Community (where she is collegiate professor) to participate.

“I wholeheartedly believe in the mission of the center to bring equity to the research, teaching and culture of the University, and to do so in a way that honors the truths of our history,” she says. “It is helping Binghamton become a far more equitable institution, which is very impactful in recruiting both new faculty and future students. It will also directly improve the lives of all stakeholders of the organization.”

Truth and Reconciliation

To date, the center’s most prominent initiative involved an intensive Truth and Reconciliation process; it led to the creation of 10 recommendations to foster true diversity and accountability at Binghamton University. These recommendations include increasing faculty and staff diversity, along with support and mentoring; establishing systems of accountability to mark how well colleges and departments are progressing toward their goals; strengthening academic and social support systems for BIPOC students; and increasing BIPOC representation among the University’s senior leadership.

Such changes are needed to fulfill Binghamton’s mission of a quality education for all. While progress has been made since the University’s founding, it’s still a profoundly white space; out of a total of 1,055 faculty members, 39 are Black, 44 Latinx, 187 Asian or Pacific Islander and six Native American.

“The commission’s recommendations will do much to enhance diversity on our campus and make Binghamton University a place that is truly welcoming and just,” President Harvey Stenger said during the Tubman Center’s grand opening. “This year we celebrate Binghamton University’s 75th anniversary, and I can think of no better way to mark the occasion than to recognize the contributions that the BIPOC community has made to our University, and to commit ourselves to becoming a fairer, more equitable campus.”

A crucial first step in equity work is listening to voices that often have gone unheard. Starting in the spring of 2021, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) accepted written and video testimonies from faculty, staff, students and alumni, and also held six listening sessions for those who wished to give in-person testimony.

Listening to and reading individual statements and testimonies was humbling, says Kendrick, who served on the TRC panel.

“The problems conveyed to us by alumni from the 1990s were remarkably similar to concerns voiced by contemporary students in spite of the intervening years,” he says. “It was impossible not to be moved by the passion that people spoke with, even about events that transpired many years ago. I felt honored to be part of it as people entrusted us with stories that were deeply personal, and at times, troubling.”

Ewuraba Annan shares this assessment. As a master’s student in human rights, she both participated as a TRC panel member and worked as a student assistant for the Tubman Center. As difficult as the hearing process was, she also found cause for optimism.

“Even during the most emotional sessions, people were still willing to share and have a relationship with the University because they know there’s a potential for change,” she reflects.

Annan’s experiences through the Tubman Center helped instill a deeper perspective on the kinds of systemic change needed to create a more equitable University. Both problems and solutions are multi-layered and require participation from everyone on campus, across disciplinary lines, she says.

Since finishing her master’s degree in May 2021, she joined the University as an admissions counselor and decided on a career in higher education. Her experiences through the Tubman Center are proving valuable in connecting with prospective students who are interested in equity issues, she says.

A Tubman Center research assistant since her sophomore year, senior biochemistry major Kelly Wu also had the opportunity to hear TRC testimony. The Tubman Center may seem an unusual choice for someone planning a future in laboratory research, but Wu has found her time there deeply rewarding.

Growing up, her family rarely watched the news or discussed politics; her parents also didn’t vote. As a result, she didn’t truly know the obstacles that many immigrants and minority families face in America.

“Working for the center has certainly changed my perspective on the importance of being active in the fight against inequality,” she says.

The ambassadors

By the time the TRC listening sessions began, the campus was already engaged in dialogue on equity issues, thanks to the efforts of TRC ambassadors from across the University’s schools and colleges. These ambassadors hosted lunchtime discussions, shared readings and engaged in one-on-one conversations, all of which promoted participation in the TRC process.

Among them was Christine Podolak, associate director of experiential education for the Master of Public Health program, who led two discussions around the theme of reparations in connection with a spring debate on the issue. She also serves on the Professional Staff Senate’s new diversity subcommittee, and also helped draft a policy statement related to racism as a public health crisis as a member of the New York State Public Health Associations’ policy and advocacy subcommittee.

During the past several years, Podolak has read up on social inequities and racism, discussed the topic with colleagues, participated in trainings and workshops, and reflected on her own personal experiences. She realized that she has much more to learn and understand about the true impact of structure and institutional barriers faced by people of color.

“I think we all have the opportunity to contribute to this important work and move toward a better, more equitable future, and remember that we always have something more to learn,” she says.

Departments, programs and schools are also addressing matters of equity on their own. The University Libraries have undertaken an initiative to identify and mitigate patterns of systemic racism in their operations, for example. They’re also conducting an audit of their personnel practices to identify and mitigate bias, and assessing their collections to ensure that they more adequately represent perspectives from beyond the dominant culture.

The Libraries also have established an Office of Inclusion, Diversity, Equity and Accessibility, and faculty and staff volunteers have created an anti-racism resource guide, Kendrick says.

Bryant and Bailey find the willingness of their colleagues to explore issues of equity and to correct structural racism encouraging.

“It turns out that once we published these recommendations, the very best-case scenario has happened so far, which is that there’s a number of folks all across this campus who have taken ownership of them,” Bailey says. “That says a lot about our campus.”

Other initiatives

Since its opening, the Tubman Center also held its inaugural speaker series on the Road to Reparations, held online due to the coronavirus pandemic. The series kicked off with Mary Francis Berry, LHD ’99, from the University of Pennsylvania, the former head of the National Civil Rights Commission, followed by Hilary Robertson-Hickling from the University of the West Indies in Jamaica and author, educator and STEM entrepreneur Calvin Mackie. More than 300 people attended the virtual events, which had multiple co-sponsors from across the campus community.

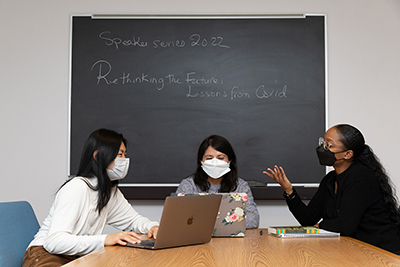

The center is now planning its second springtime speaker series and establishing a faculty affiliate program, as well as fundraising for several initiatives, including a faculty fellowship and a Tubman Scholars program to provide an opportunity for undergraduate and graduate students to understand the roots of equity and freedom work.

One of the goals behind the faculty fellowship is to give BIPOC faculty more opportunities to work on their research and advance their careers. That’s often a stumbling block for people moving through the ranks of academia, Bailey says. Financial resources and mentoring support may help bridge the disparities in faculty diversity numbers, along with promoting excellent scholarship.

Plans are also under development for a future Harriet Tubman statue and memorial garden on campus. The site will represent one stop on the Underground Railroad, as well as identify other abolition sites in Upstate New York.

“Having a monument of Harriet Tubman and a memorial garden on campus will prompt all who walk our campus to see, feel and remember the atrocities of slavery and reaffirm a commitment to bring equity and justice to not just our campus, but wherever they walk as alumni,” Jaussi says.

Just like conductors on the Underground Railroad, the Tubman Center encourages all members of the campus community to become involved in equity work in whatever way they can, whether through sharing their talent and expertise, volunteering or offering financial support. All are necessary to create a more just society and culture.

That work can evolve, too, much as Tubman’s did: After the abolition of slavery, she created a senior home for the formerly enslaved and engaged in other work to support her community. With an eye on the future, she also set aside funds to continue her work long after her death.

“It’s a wonderful guide for us,” Bryant says of Tubman and her legacy. “We’re trying to move forward in and be present in the now, but also have eyes on the future and how we envision what the center could become.”