Bringing the truth into focus

Two alumni collaborate on nonfiction TV, documentary films

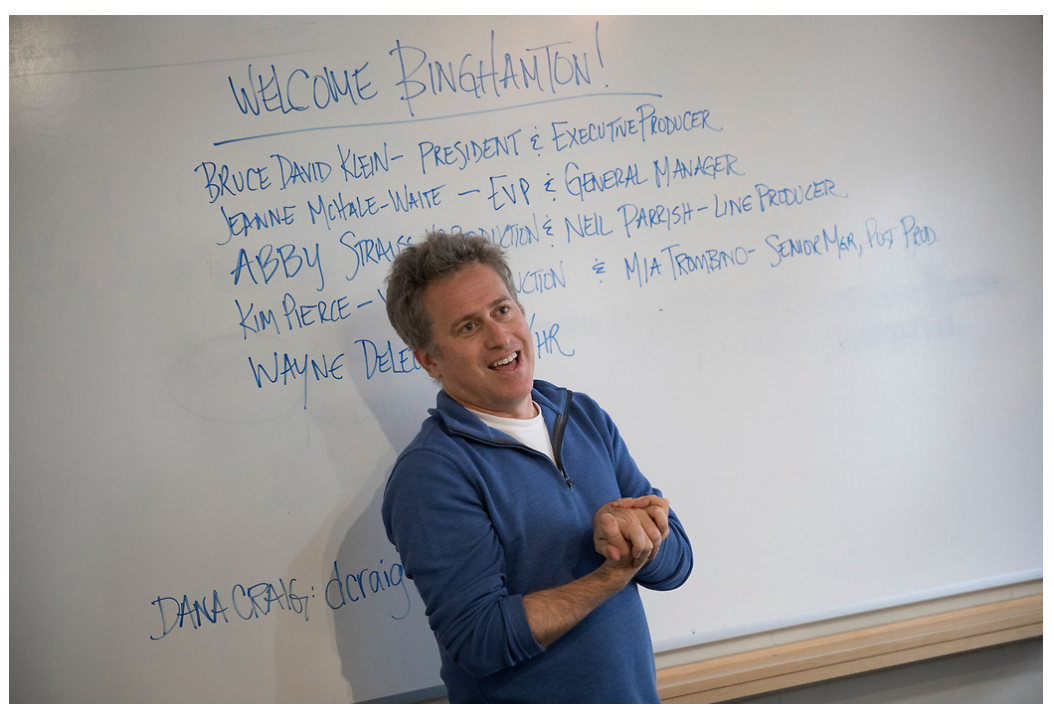

A decade ago, Bruce David Klein ’85 visited the Binghamton University campus as a guest speaker for the Cinema Department. He told students about how the company he founded, Atlas Media Corp., grew into one of the largest producers of nonfiction television in the U.S., and how he’s written, directed and produced a range of acclaimed documentary films.

Alex Goldstein ’12 was nearing graduation. As a cinema major, he’d discovered a love of nonfiction storytelling and wanted to break into the industry. He and Klein connected briefly at the University’s public relations office (where Goldstein was an intern), and then Goldstein boldly followed Klein and his wife to the elevator to make a pitch for any available jobs.

If this were a clichéd moment from a Hollywood script, Klein would have taken a chance on the kid and hired him on the spot. Instead, they met again six months later in a different elevator at the Atlas Media offices in New York City.

“Hey, Bruce,” Goldstein said. “I’m Alex. We met at Binghamton.”

“Yeah, I remember that,” Klein replied. “So what are you doing here?”

Goldstein smiled. “I’m working for you now!” He had made his own connections at Atlas Media and landed a role behind the scenes of Hotel Impossible, a production for the Travel Channel.

Among several other projects since then, the duo worked closely on Icahn: The Restless Billionaire, broadcast this spring on HBO. The documentary profiled Wall Street titan Carl Icahn, the activist investor — or corporate raider, depending on your opinion of his tactics — known for his deals with Tappan, Texaco, Apple, Trans World Airlines and other big-name firms.

The film earned critical praise similar to Klein’s high-profile documentaries Meat Loaf: In Search of Paradise (2008) and Best Worst Thing That Ever Could Have Happened (2016), about the original Broadway production of the Stephen Sondheim musical Merrily We Roll Along.

Bruce, how did Binghamton influence your filmmaking career?

KLEIN: When I was young, I made home movies and was always obsessed with cinema. I majored in creative writing and psychology, thinking that I would be a psychologist. In my sophomore year, down in the basement of The Union, there was the sign that said “Harpur Television Workshop,” but I never saw anybody in there. I got a custodian to open it, and it was like a scene out of a movie. There were cobwebs on 1960s-era giant black-and-white cameras, along with rows and rows of giant mixers and switchers and all this really old equipment. I’m not a technical person, but I saw this button that said “on,” and I literally turned it on. The whole studio came to life.

I started making these public-access shows. I was an avant garde filmmaker, more artsy kind of stuff. I remember doing a documentary on the Hari Krishnas in Binghamton. Because I was also a musician, my friend and I did this performance piece that culminated with me playing a song on the piano and lighting it on fire.

The time I spent in the Harpur Television Workshop usurped the time I was spending applying to graduate programs in clinical psychology. I realized I wanted to communicate on a larger scale — to mold millions of minds at a time as opposed to one at a time.

Alex, you were at Binghamton more recently than Bruce. What was your experience?

Goldstein: I went into college thinking that I wanted to be a filmmaker. After my first couple of cinema courses, I thought maybe it was a little too experimental for what I was going for, so I stayed a cinema minor but decided I wanted to become a lawyer.

As I was doing pre-law, I joined an acapella group on campus and I made all the videos for the group. We made these Saturday Night Live-style skits, I directed them, and I was getting really good at it. After a while, I thought, “I don’t want to be a lawyer. I have a lot more fun doing this film stuff. Let me see if I can squeeze out a cinema major.” I barely graduated on time!

I loved being a part of the cinema community at Binghamton. I loved being in that basement of the Lecture Hall. You felt like you were doing something different from everybody else on campus.

What drew you to documentary filmmaking?

GOLDSTEIN: I thought originally scripted projects were inaccessible. I started experimenting with documentaries, and I fell in love with the process. I did a project in my senior year at Binghamton that traced my family lineage. That was the first time I saw the magic of that medium.

KLEIN: Take the wildest, most outlandish film and compare that to real life — it doesn’t compare. One of my favorite movies is A Clockwork Orange, which is off-the-charts wild and unusual and odd. We have seen things that are 10 times crazier in real life.

Also, Atlas Media started at the dawn of nonfiction, unscripted television. Before that, the only time you saw a documentary was on PBS. Then MTV was doing documentaries, the History Channel was created, the Discovery Channel was created — there was this golden age of nonfiction, unscripted programming that is still happening. Ten years before I started out, you’d maybe pitch a documentary to PBS or do one that’s in a film festival but would not get a wider audience. Today, people buzz about shows like Tiger King and Making of a Murderer. They are in the zeitgeist.

On a basic level, what’s the role of the producer? And how does it fit into the overall hierarchy of a TV show or film?

GOLDSTEIN: With documentaries, the producers are the all-around make-it-happen people, getting their hands dirty, making sure that everybody’s doing what they have to do and that the interviewees are happy. You’re kind of a Swiss Army knife of creativity and mechanical knowledge — a writer, a logistics manager, sometimes a technical supervisor.

KLEIN: Every production is a war. It’s a battlefield, and you’re getting shot at by an enemy. They’re using guns. They’re using grenades. They’re using a nuclear bomb sometimes. Your goal as a producer is to avoid those — and if it’s impossible to avoid them, then to make the aftermath better.

Everything in the universe tells you that you can’t make it happen. It’s the producer’s job to say not only yes, but we’re plowing through and we’re going to do it, because that’s the only way any productions get done.

For the Carl Icahn documentary, you had to convince him to participate. How do you deal with reluctant subjects?

KLEIN: Every subject is reluctant, and for an obvious reason — nobody wants their private life and thoughts broadcast to millions of people without some control over what it says. The trick of the documentarian is to find a way to capture the truth and make the subject feel very, very comfortable.

With Carl, because he is a high-profile, very public, multi-multi-multibillionaire, and because he is infamous for his tough dealmaking, he sees everything as a negotiation, including whether he should be in a documentary or not. He was convinced that a documentary capturing the history of his dealmaking would be fine. But when people see that he makes a billion dollars cutting a deal, the natural, inquisitive question from a documentary viewer is: What makes him that way? What’s his unique DNA that makes somebody like him able to do that? We have to show his childhood, we have to show what he’s like today and how he goes about his life. He was less convinced on that side.

When you’re in Carl’s presence — and hopefully in the film as well — you get the feeling that this is a really unusual mind that’s telling you exactly what he thinks at any given moment. And if he’s not, he’s calculated what he’s telling you in a way that also reveals his personality. As a documentarian, your job is to reveal the person.

Alex, what have you learned about documentary filmmaking from working with Bruce?

GOLDSTEIN: Bruce talks about the difference between poetry and prose, which I always thought is a profound way to talk about documentaries and what we’re trying to do. We go beyond journalism and create a kind of poetry with the films that we’re making.

KLEIN: One thing that Alex grasped immediately is that every documentary has its own path. The subject and the world you’re in speak to you, and they tell you what it should be. Any film that we’ve made — our Sondheim film, our Meat Loaf film, our Icahn film, the one we’re working on now — takes its own path and comes out differently, because the material is so different and the process is different.

What advice would you give to current and future students who are looking to make a career in film and TV?

GOLDSTEIN: The hardest part is making the decision. Once you decide, use all the tools available, tell everybody you can that this is what you want to do and that this is what you’re going to do, and the universe will conspire for your success.

KLEIN: Carry the scrappy, hardworking Binghamton spirit into everything you do in your career, and I guarantee you will be successful beyond your dreams.