History inside history

An independent study leads to an unexpected discovery

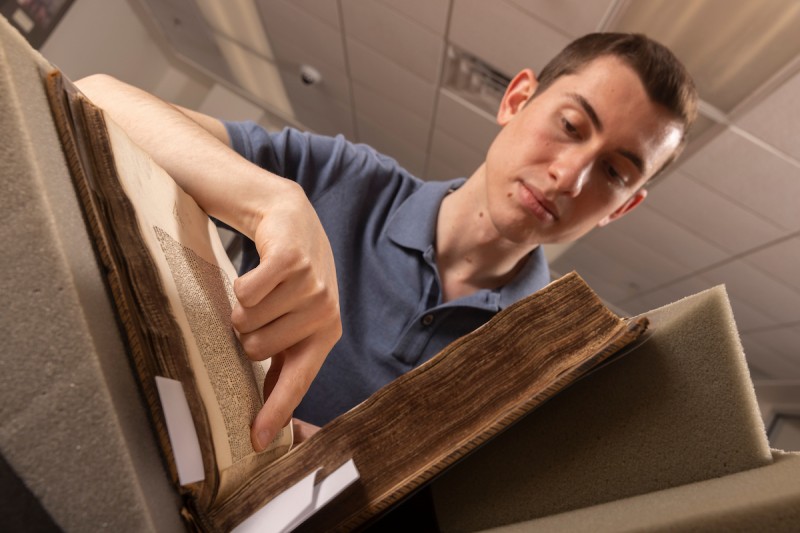

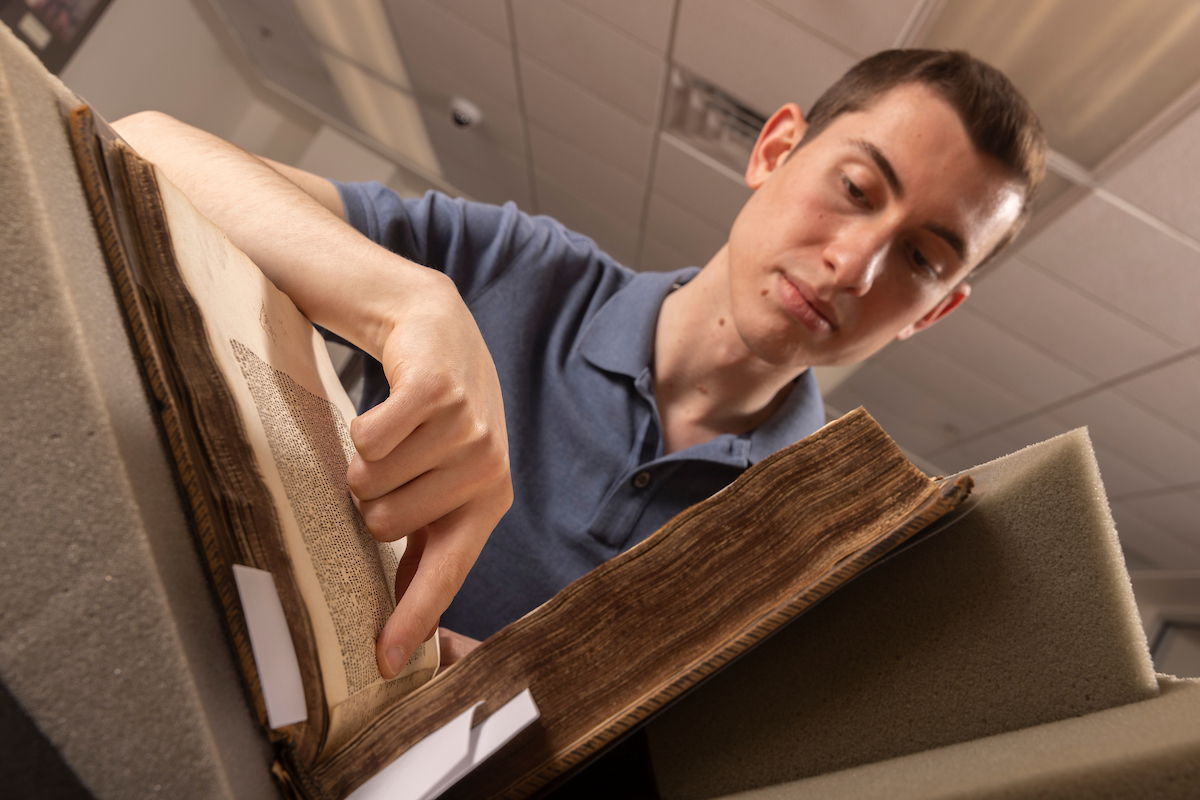

As Zack Ben-Ezra turned the pages of a centuries-old book, he noticed something unusual.

The history major discovered remnants of even older books — unidentified medieval manuscripts — hidden within the bindings of two of the six incunabula within the Binghamton University Libraries’ collection. Incunabula are books printed between about 1450 and 1501, covering the first half-century of movable type printing in Europe.

Ben-Ezra carefully examined the books for clues about their construction, former owners and patterns of use. The information he uncovered will be submitted to Material Evidence in Incunabula, an international database that helps track the movement of books across Europe through the centuries. The research was carried out as part of Ben-Ezra’s independent study under Assistant Professor of English and Medieval Studies Bridget Whearty and Special Collections Librarian Jeremy Dibbell.

“We found manuscript waste in two of these books,” says Ben-Ezra, a senior who is headed to law school this fall. “When they were being bound, the shop likely would have scrap pieces of paper or parchment around that they would repurpose, binding them in the book to give it structural support.”

These scraps offer a glimpse into earlier, handcrafted manuscripts some considered lost. As fate would have it, Ben-Ezra discovered the scraps inside the gutter — the indentation where the pages meet when the book is opened — of the very first incunabulum he leafed through.

That book was later examined by researchers from Rochester Institute of Technology, who scanned the incunabula using multispectral imaging to see features not visible to the naked eye.

“This kind of work shows the radical potential of rigorous, supported research performed by ambitious undergraduates at Binghamton,” Whearty says. “Zack’s discoveries gave him a fabulous independent study, working hands on with rare books after a year of classes almost exclusively online. But that’s not the end of it. His work is already providing a strong foundation for future work by Binghamton students, by outside researchers and by international scholars studying the long history of books.”

For Ben-Ezra, the independent study gave him a fuller appreciation of history, bringing to life a world now centuries gone. Consider marginalia, the notes and doodles that readers sometimes scrawl in books even today, he says.

“When you see these little notes and these little doodles, you begin to see that these are real people,” he reflects. “That changed my view of history and the way we study it.”