Touching the past

Students get up close and personal with the Middle Ages

“Are everyone’s hands washed?”

Heads nod in Distinguished Professor of English Marilynn Desmond’s Women and Society in Medieval Literature class, taking place this spring semester day in the Binghamton University Art Museum’s Kenneth C. Lindsay Study Room. A strange yet palpable hush surrounds the books on the table — what Kiernáin Sullivan, a master’s student in another class, describes as an aura.

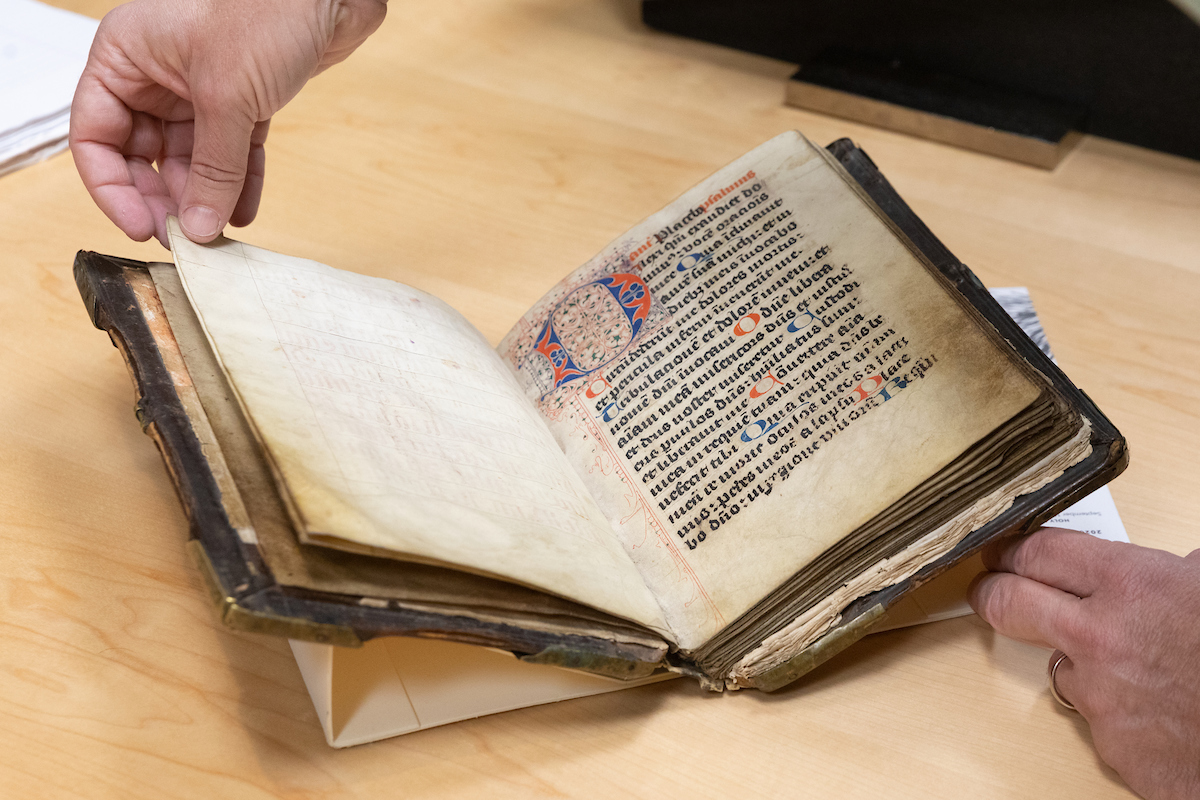

Desmond’s hands creak open the manuscript on display — a 15th-century biography of early Christian hermit-saints. It was created in Italy, probably in Venice and most likely from the skin of goats; the side where the hair had been scraped from the skin still bears a faint blurring fuzz.

“When you’re reading a book, you’re reading an animal skin,” Desmond explains.

At her urging, the students turn the pages of the Lives of the Desert Fathers and then the paper-thin pages of a 13th-century pocket Bible, its print so tiny that the human eye can’t read it unaided. A blind student is aided by Desmond, who guides her hand along Lives’ vellum pages, taking care not to touch the fragile ink.

“It’s strange; you’re touching something that was once alive,” reflects McKenna Bunnell, a senior comparative literature major, after running her finger along the edge of the Bible folio. “It’s so different to have it in your hands and feel it.”

The manuscripts, among nine that also included a 13th-century Psalter, which contains the biblical Book of Psalms; a 15th-century liturgical prayer book known as a breviary, a 15th-century French religious text and a printed, 16th-century Book of Hours, were on loan from the prominent bookseller Les Enluminures. While they were featured in a spring museum exhibit on “The Materiality of Medieval Manuscripts,” they weren’t simply objects of art, viewed from behind a pane of glass.

Students in nine classes used the manuscripts for translations from Latin and medieval French, research into the material history of the book or insights into medieval music. They read them, sang from them, studied them — and, yes, touched them.

“It’s such an amazing opportunity to have access to these sources,” says first-year vocal performance major Abby Sprague, who studied the 15th-century Office of the Dead with her music class.

“Some of these texts are 900 years old,” adds sophomore Adrian Finney, a major in music composition. “It puts things in perspective.”

When books were high-tech

We may not know the word “codex,” but we know its shape intimately: a rectangular cover encasing sheaves of paper ordered from front to back. Even digital texts typically preserve the form of the printed book, rather than its predecessor in the ancient world: the papyrus scroll.

Papyrus lasts only 400 years at most before crumbling into dust, a situation further complicated by an unwieldy, rolled-up format that made accessing information difficult, Desmond recounts. By copying the scrolls into books, medieval scribes saved ancient knowledge from being forever lost — a far cry from popular ideas surrounding the Dark Ages.

“Without the technology of the book, we would have only fragments of ancient literature,” Desmond says. “The book was an advance in every possible respect.”

The oldest medieval books date back to the sixth and seventh centuries when books were the ultimate luxury item, their use restricted to clergy and the aristocracy. By the end of the 15th century and the advent of the printing press, however, average households could aspire to own a paper book: most often a Book of Hours, a text often associated with women’s religious devotion, as Psalters were more likely to be used by men.

Medieval books weren’t stored on their spines, as they are today; rather, they were stacked on their sides. Clasps — such as the one that still graces the 13th-century Psalter — kept the books from opening up and leaping off the shelves when the parchment pages swelled with humidity.

They’re kept in temperature-controlled environments today, and handling them requires special care. Manuscripts under study are placed on supports and opened gingerly by faultlessly clean hands, which touch only the edge of the page and never the ink. Even pens are banned in favor of pencils to prevent stray ink from damaging a priceless artifact.

Working with the physical books was a bit nerve-wracking, students admit.

“I was sitting with someone else who was working on it, and we were both like, ‘Do you want to turn the page or should I turn the page?’” recounts sophomore chemistry major Jillian Karlicek, who wrote a research paper on the 15th-century Office of the Dead for a class with Desmond. “Holding something that old — it’s just incredible to think about the amount of history and the amount of time other people have spent with this book.”

In her paper, Karlicek focused on how the manuscript came to the Cologne church that used it as a liturgical text and what it shows about the period’s changing sociopolitical landscape. Created in 1487 as a gift from an archbishop in a neighboring town, the manuscript collected prayers and psalms recited during Christian rituals surrounding death.

“The edges of the pages themselves are pretty much just black with dirt and use,” Karlicek says. “It’s incredible that it lasted so long, despite being used nonstop for about 300 years or so.”

Associate Professor of Musicology Paul Schleuse knows precisely why certain pages were so worn: This is where the monks would have flipped back to the previous section of the liturgy as they sang, he explains to his music history class.

Libera me, Domine, de morte aeterna, the ancient scribe wrote in the Office of the Dead, words that are now part of the Requiem Mass. Other sections now comprise part of today’s liturgy for Holy Week.

… dies illa, dies iræ, calamitatis et miseriæ …

Black dots indicate music notes on thick stems, known as Hufnagel notation, on a five-line staff similar to our own clef staff. Schleuse pauses and hums to himself briefly in a minor key, then begins to sing. The class joins in, an impromptu Gregorian chant pleading with God for deliverance: Kyrie eléison, Christe eléison…

While most of the texts are handwritten in Latin, students didn’t need to master ancient languages to fully appreciate the books’ importance, observes Assistant Professor of History Sean Dunwoody, who introduced the Office of the Dead, the breviary and the pocket Bible to his Introduction to Medieval and Early Modern Studies class.

With her classmates, first-year history major Farah Mughal marveled over the physicality of the objects and the parchment’s peculiar feel. Junior Brandon Worrall, an economics major, was also struck by the experience.

“This was not something I was expecting to do in class,” he offers.

Ancient and modern

So, what does vellum feel like? Sullivan, who studied the Psalter for Desmond’s upper-level course on Gender, Sexuality and Manuscripts, compares the sensation to suede, softened by the centuries.

But some aspects of the text are surprisingly modern. A master’s student in English who is also earning a certificate in medieval studies, Sullivan explored transgender themes in the 13th-century Psalter, which comes from southern Germany. It contains only three images; two of them — depicting St. Dominic and St. Francis — had been defaced, likely around the period of the Reformation.

The remaining, complete image shows the Archangel Michael slaying a dragon. With long golden hair and flowing robes bearing traces of the original gold leaf, the spear-wielding angel has an androgynous appearance.

“Within the context of the Bible, angels are understood to be genderless, as they have no corporeal form and are considered spirits,” Sullivan says. “Essentially, what you have is a Psalter that is typically oriented toward masculinity that had all its male characters removed.”

Much like writers of today, the scribes of old made spelling errors and other mistakes. The texts included corrections, abbreviations and even new pages sewn into the books to replace earlier, error-laden sections.

Associate Professor of French, Medieval Studies and Translation Studies Jeanette Patterson’s class on French Before France: Medieval Languages and their Stories analyzed a 15th-century manuscript in Middle French whose title translates to The Seven Fruits of Tribulation. Students translated sections of the text and wrote a commentary on language use, context and their approach to translation.

Junior Alexandra Keough, a political science and French and Francophone studies major, translated the first few pages, which laid out the purpose of the book: to show the spiritual importance of suffering. The text begins with a tale of St. Ambrose, who chose to leave a wealthy man’s hostel after finding out the man had never known travail, making him likely to see eternal damnation. Biblical tales follow: the trial of Susanna, unjustly accused of fornication; Job and Tobias; David and Goliath.

Reading medieval handwriting presents an array of challenges, including the lack of standard spelling, apostrophes and modern punctuation, along with a script that makes it difficult to differentiate letters. Oftentimes, students figured out words and meaning through context.

“It’s like playing Middle French Wordle,” Patterson quips.

Senior Emily Ronan, a dual major in French language and linguistics and biological sciences, struggled to translate her assigned pages from a PDF. An hour spent with the physical book in the Lindsay Room made all the difference, she says, and underscores how much students and scholars can learn from interaction with physical texts.

And yet, across the centuries, perhaps ancient and modern scholars aren’t so dissimilar. Senior Liam Kerrigan, a dual major in Russian and French and Francophone studies, points to the misspellings and drawings in the margins.

“It’s fun to realize how not-different we are from the people who wrote these manuscripts,” he says.