The birds and the bees: Research links public school sex ed and eugenics

When it comes to sex education, the actual doings of birds and bees may seem the least problematic part.

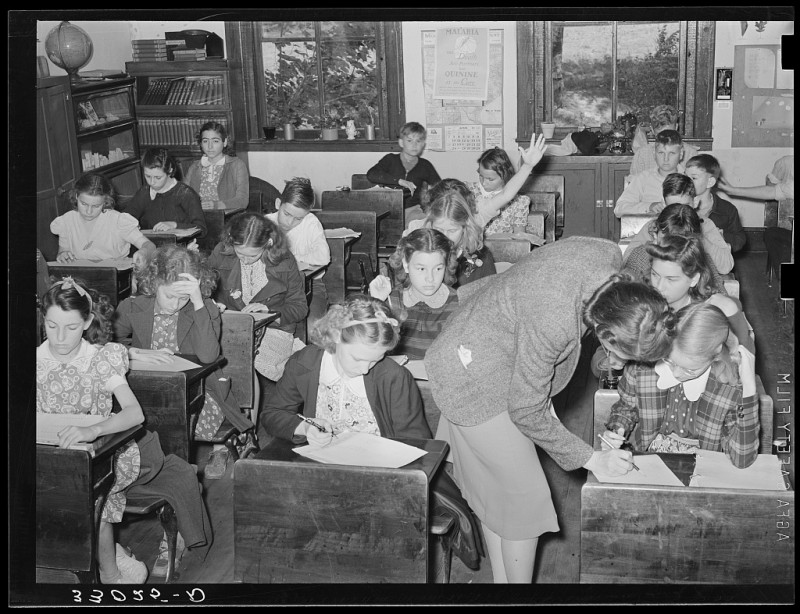

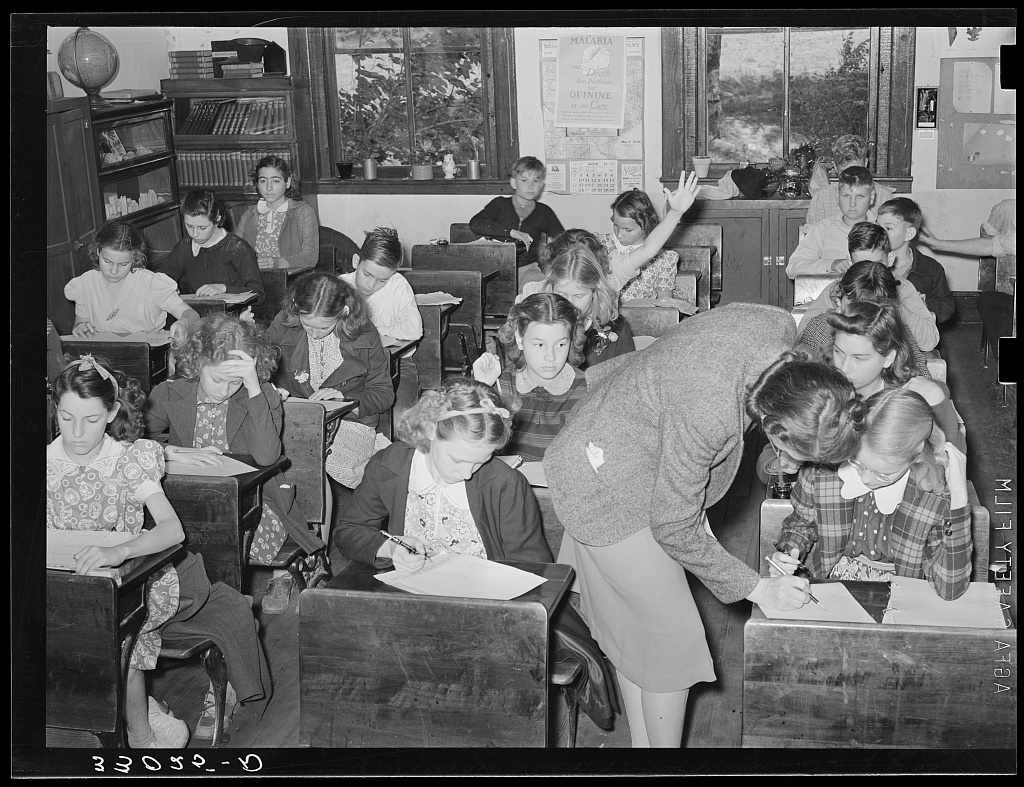

But when the principles of biological reproduction first entered public school classrooms in 1913, they were intended to instill a specific ideology: eugenics.

“They accomplished this through what they called ‘nature study’: This is how flowers reproduce. This is how bunnies reproduce, and chickens and moths,” explained Julia Haager, MA ’15, PhD ’22, currently a visiting assistant professor of U.S. and public history at the College of Charleston in South Carolina. “Eugenics was infused into these discussions of animal reproduction. There were heavy-handed messages like ‘You need to reproduce in this way and select a mate to carry forth these traits that are better for society’ and it was implied that if you didn’t do so you were not a being a good citizen.”

Haager was a finalist for the 2022 SUNY Chancellor’s Distinguished Dissertation Award. Her project — “Teaching Responsible Reproduction: Eugenics and Sex Education in the United States from the Progressive Era through World War II” — was the only one in the humanities selected for the honor.

“I was interested in sex education from my own background. I had worked with pregnant teens in public schools before, so I wanted to know more about the history of public school sex education,” she said.

While previous scholarship considered the overt role of eugenics in incarceration and forced sterilization, Haager’s research explores how the ideology influenced less legally focused venues, such as sex education in public schools.

In the 19th century, sex education was instilled by parents in the home and was of a religious and moral nature, focused on marriage and monogamy. At the turn of the 20th century, the situation changed, Haager said. More people began to view sex as a public health concern, and public schools as the place to address it.

Teaching eugenics

The controversial topics we typically think of when it comes to sex education — menstruation, puberty, dating, marriage, parenthood, abstinence — weren’t added until World War II, prompted by rising divorce and juvenile delinquency rates during the Great Depression. Rather, the first few decades of sex education focused on biological reproduction, cell division and heredity, shying away from any mention of human sexual intercourse.

The understanding of heredity in those days was primitive in comparison to today; DNA’s double-helix structure wasn’t discovered, after all, until the 1950s. Along with physical traits, many believed that personal qualities were also hereditary, including monogamy, lying, criminality, poverty and intelligence — or, in the parlance of the day, “feeblemindedness.”

Public schools repurposed adult-themed informational materials originally intended for soldiers during World War I, driving home the message that one’s choice of mate carries societal repercussions.

In today’s world, eugenics has a fearsome reputation, especially due to its use in justifying Nazi atrocities and other abuses, such as the forced sterilization of women, many of whom were of color. But prior to World War II, eugenics was considered scientific and the word itself was used colloquially, as a synonym for “hygienic” and “helpful.” Newspaper advertisements promoted “eugenic” shoes and beauty products, for example.

“People saw eugenics as a net good,” said Haager, who is currently turning her dissertation into a book.

This was the age of “better baby” and “best family” contests. The American Social Hygiene Association gave eugenics lectures to teachers, sponsored by U.S. Public Health Services.

In the era of segregation, that included Black schools, who taught the principles of eugenics as a way to achieve “racial uplift” and a secure place in the middle class. Interestingly, this was also a period in which a growing number of women from immigrant or working-class backgrounds entered the teaching profession, creating an apparent contradiction: Women whom eugenicists would have considered “racially unfit” were increasingly the ones teaching its principles in the classroom.

They had incentive: Teachers received tangible benefits from teaching sex education and partaking of eugenics-related professional education. That included higher salaries, and promotions to school counselor, nurse or administrator. While the role of racism in eugenic laws is well-known, the ideology itself encompassed a wide range of other traits — enabling proponents to pick and choose their areas of heritable concern.

“If the teachers were very concerned about urbanization’s effects on their communities, they might teach about poverty, criminality and disease as inheritable traits. If they were really worried about intellect, they might latch on to the parts that focused on disability and were separate from racial hierarchies that were the emphasis in debates about eugenic law,” Haager said.

History and the public good

Eugenics began to fall out of favor in academia, although the time frame is a matter of discussion. The downfall may have initially been prompted by a schism in the American Eugenics Society, but by the end of World War II, the word “eugenics” was rarely used.

That doesn’t mean that the eugenicists disappeared. Proponents rebranded themselves as marriage and family therapists, child psychologists, and experts in juvenile delinquency, Haager said.

“The messages in sex education weren’t any different; they were just eugenics in a different package. If you marry and reproduce with someone who has the right hereditary traits, you won’t have children who are delinquent or have psychological problems and society will be better off,” she said.

In fact, the theory never really died; consider, for example, you see some of the same eugenic arguments about heredity and improving society in the recent promotion of “replacement theory” on the political right, or the quasi-ethical arguments surrounding gene-editing technologies, disability and “designer babies.”

“In schools, we have this widespread assumption that topics like genetics and heredity are value-neutral; they’re the safe part of sex education that parents don’t fight over,” Haager said. “But medical bioethicists would scratch their heads at that; these topics aren’t value-neutral.”

Haager’s current research also touches on social services and sexuality; she is working on a project with Binghamton University Associate Professor of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies Sean Massey on the history of the organization Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) from 1980 to 1998. Their research looks at the diversity of AIDS service workers and volunteers in New York City during that period and how GMHC, at one point the world’s largest AIDS service organization, innovated during the public health crisis.

So far, they have conducted 70 oral interviews with former GMHC staffers and volunteers, which will be archived at the New York Public Library. They’re also working on a book.

As a public historian, Haager’s goal is to make history accessible to wide audiences, she said. In Charleston, she is tackling another controversial issue: the portrayal of enslavement in public history.

Sometimes — as was the case with eugenics education — academia may fail to consider how their ideas are being used by the larger public, she said.

“We have a responsibility to pay attention to where our ideas go,” she said. “History has the ability to be weaponized, and as academics we have an ethical responsibility to pay attention and empower people to use it for the public good.”