Modern scribes: How medieval books go from parchment to the cloud

Like many poets, Thomas Hoccleve had a day job. Sometimes his workday complaints slipped into his poems: eyestrain from long hours staring at text, backaches from a lack of ergonomics, difficulty standing up straight.

While Hoccleve was a 15th-century scribe, his experiences aren’t that far removed from the teams who digitize texts today, which include librarians, curators, imaging specialists, conservators and preservation experts, catalogers and metadata specialists, technologists, project managers, production coordinators and sometimes students. As Hoccleve himself knew, copying texts is exacting and complicated work — and often unappreciated by readers.

That’s a dynamic that Binghamton University Associate Professor of English Bridget Whearty hopes to change. In her new book, Digital Codicology: Medieval Books and Modern Labor, she introduces readers to the digitization process and the highly trained professionals who perform this work.

“In medieval studies, we use digital copies constantly. If you’re a literary scholar, it’s really easy to pull up a copy of a poem you’re working on and see it in a 15th-century scribe’s handwriting,” she said. “But even though we use them, we don’t necessarily think about who makes them and how and why they’re made. And that’s funny, because we spend a lot of time thinking about those exact questions when it comes to the original copies.”

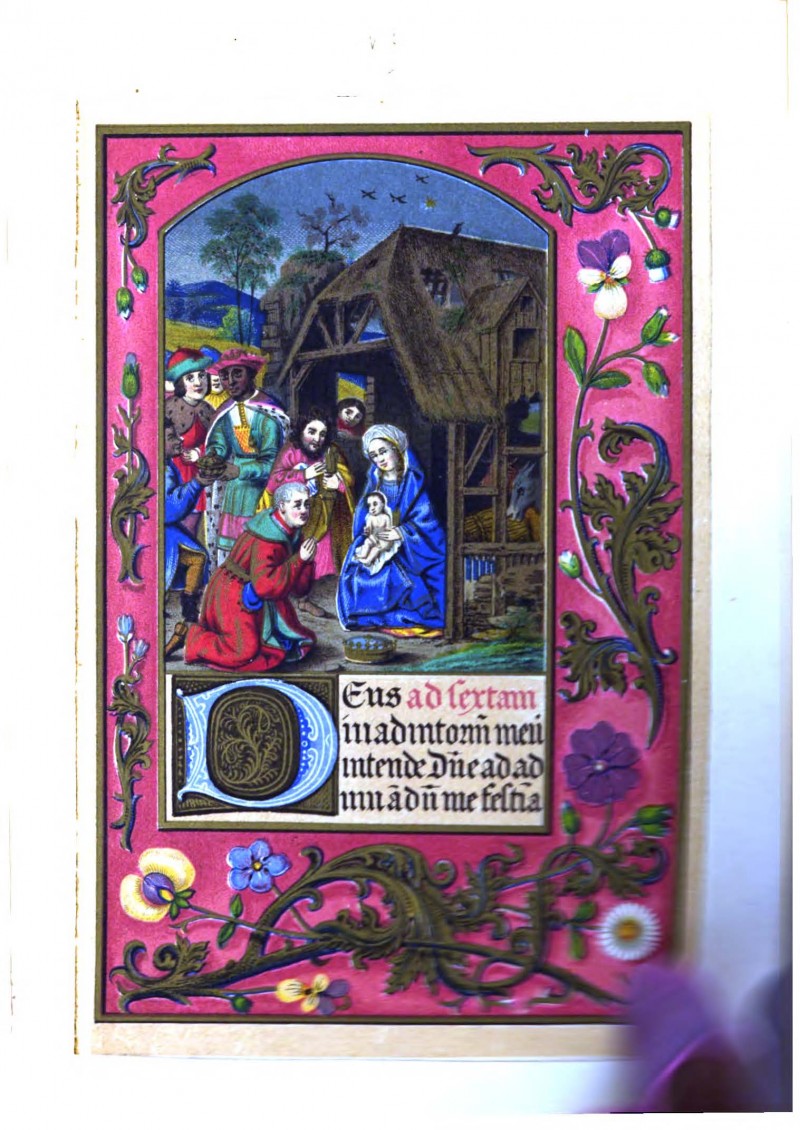

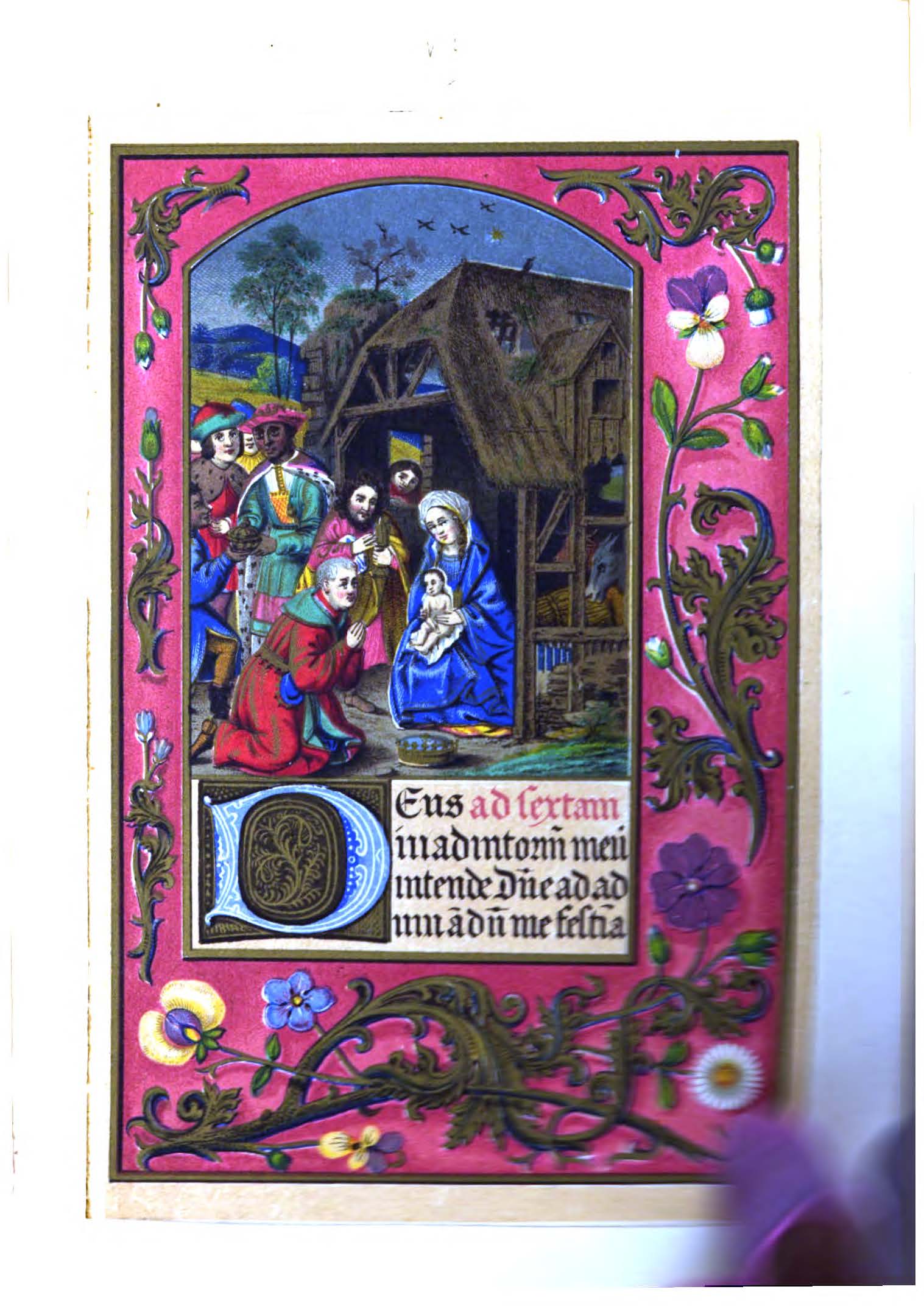

Whearty traces the preservation of manuscripts through media history, from print to photography and finally the internet, demystifying digitization along the way. To that end, she examines late-1990’s projects such as Digital Scriptorium 1.0 alongside late-2010’s initiatives like Bibliotheca Philadelphiensis, and world-renowned projects created by the British Library, Corpus Christi College Cambridge, Stanford University and the Walters Art Museum against in-house digitization performed in lesser-studied libraries.

She also traces the story of one manuscript: a book of Hoccleve’s poetry, created in the 1420s by his own practiced hand, which now resides at the Huntington Library in California. First printed in 1796, it was put on microfiche in the late 20th century and photographed for digitization in the early 21st century. During each rendering, editors, printers and copiers made choices about what needed to be represented and preserved.

While some medieval scribes doodled in the blank spaces of their books and left notes to future readers, others were professionals who worked to create uniform copies stripped of the marks of their copyists. Today, digital imaging teams by and large try to hide every trace of their own labor in the copy’s creation.

“Digitial Codicology is a story about medieval books, and it’s a story about all of the people who have loved and cared about them, and copied them with print, photography, microfilm and digitization,” Whearty said. “It’s also about learning to see and value that labor with the same kind of rigor that we value medieval scribes.”

From scribe to technician

Digitization of museum texts began in earnest in the 1970s, although the process has changed dramatically through time. It still varies from institution to institution, depending on the purpose of the project and the funder — a reality strikingly similar to the creation of the original books.

Whearty was a postdoctoral fellow in Stanford University Libraries’ Digital Library Systems and Services Department, where she had the chance to see Stanford’s digitization lab. An eye-opening experience, the fellowship

In November 2014, Whearty received permission to follow the digitization of a single medieval book at Stanford, even getting to do some of the work as one of two photographer’s assistants. The similarities between modern and medieval scribal work were striking, down to the eyestrain and backaches from looking at a text too long.

And there were other echoes and similarities, beyond the aches and pains of copying medieval books. “Benchmarking in digitization is a lot like a master scribe planning out the text, and like figuring out where the illuminated initials will go well before anyone actually started copying,” she offered.

While she found digitization exciting, many colleagues in academia tend to misunderstand or even devalue the process and the people who perform it, she discovered. During a casual conversation at an academic conference, a fellow scholar chided Whearty, asking, “Why don’t you work on the real thing?”

“How can we care as medievalists so passionately about people who died 700 years ago, and yet be