Down under: Graduate student conducts maritime research in Antarctica

Rachel Meyne uses tiny fossils to reconstruct the conditions in an ancient sea

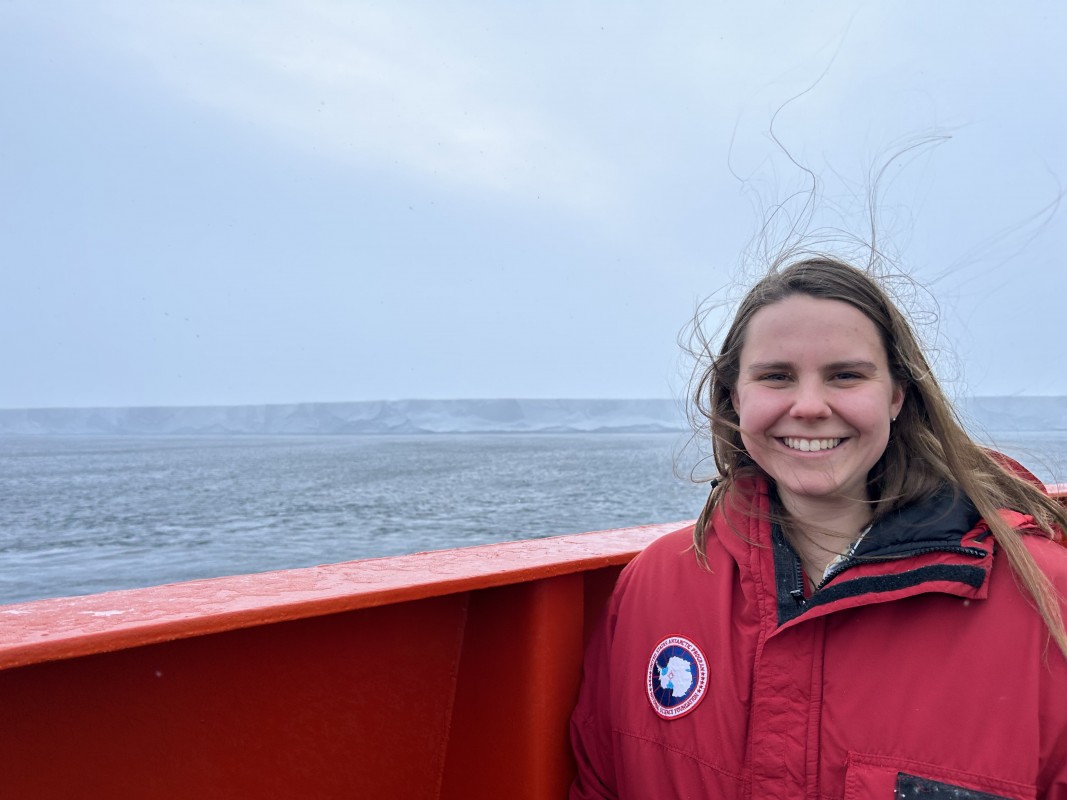

From the icy swells of the Southern Ocean, the Ross Ice Shelf reaches into the heavens — a forbidding white wall. Beyond, unseen, lies Antarctica with its penguins and scientists.

The southernmost continent is a world away from Binghamton University, where Rachel Meyne is working on her master’s degree in geological sciences. She recently spent 2½ months on board the Nathaniel B. Palmer, a U.S. Antarctic Program research vessel, as part of a National Science Foundation-sponsored trip.

She was one of several graduate students on board the ice breaker, which she describes as “the coolest way to explore the continent.”

Originally from Texas, Meyne received her bachelor’s degree from Colgate University. She signed on to the research project before she came to Binghamton by way of Colgate Professor Amy Leventer, her advisor at the time. Meyne was supposed to sail in 2020, but the journey was postponed by the pandemic.

Researchers on the Antarctica trip were focusing on the mechanisms and processes that led to the retreat of the Ross Ice Shelf during its last deglaciation period; the shelf is attached to the continent but also extends out into the ocean.

Meyne’s own research focuses on diatoms, which are single-celled microalgae with a silica shell. Sometimes called “living opals,” these tiny fossils resemble glass and range in shape from the circular to the needle-like. They’re drawn up through sediment cores bored into the sea floor, and can give researchers insight into the conditions of ancient oceans.

“We use these diatom microfossils to classify different paleo environments,” Meyne explained.

The team boarded the Palmer in Lyttleton, New Zealand, on Dec. 15; because some team members tested positive for the coronavirus, they quarantined on board and then set sail on Dec. 26. It took 10 days to reach Antarctica, during which time Meyne discovered the joys of playing ping pong on a boat in rough seas. She’s not bothered by motion, she said, although she took medication for seasickness during the journey.

During the trip, the team remained on the open water except for a brief visit to McMurdo Station, where they explored trails and watched biologists check on the local seal population. Days were fascinating, unsurprisingly cold but also long, with 12-hour shifts containing a range of research-related tasks, from working with sediment cores to sampling seawater and imaging the ocean floor.

“It’s a great opportunity to learn about data collection in the field,” Meyne said. “It felt like such a privilege and I was very motivated to make the most of my time on board and collect as much data as I could.”

She’ll use that data in her own research, under Assistant Professor of Earth Sciences Molly Patterson, her advisor at Binghamton.

Prior to the trip, Meyne never imagined herself becoming a polar scientist. It’s now in the realm of possibility, although she plans to work and travel for a few years before pursuing her doctorate.

“Working in Antarctica is like working in the wilderness; by its nature, it feels exploratory,” she said. “Polar science really feels like we’re answering non-trivial questions about how the Earth works.”

In the Earth sciences, field experiences are crucial for students, but they’re not always accessible for those who are researching environmental change in remote regions, Patterson said. Meyne’s experience in Antarctica will benefit her in many ways as a researcher, including the connections she made with other shipboard scientists.

“She sailed with a great group of scientists from a variety of universities and was exposed to numerous scientific methods, and now she gets to also collaborate with these individuals on her MS thesis work,” she said. “As her advisor, I really cannot think of a better experience to train the future generation of polar researchers than the one she is experiencing.”