Black monument: How sculptor Ed Wilson brought Black history into the realm of public art

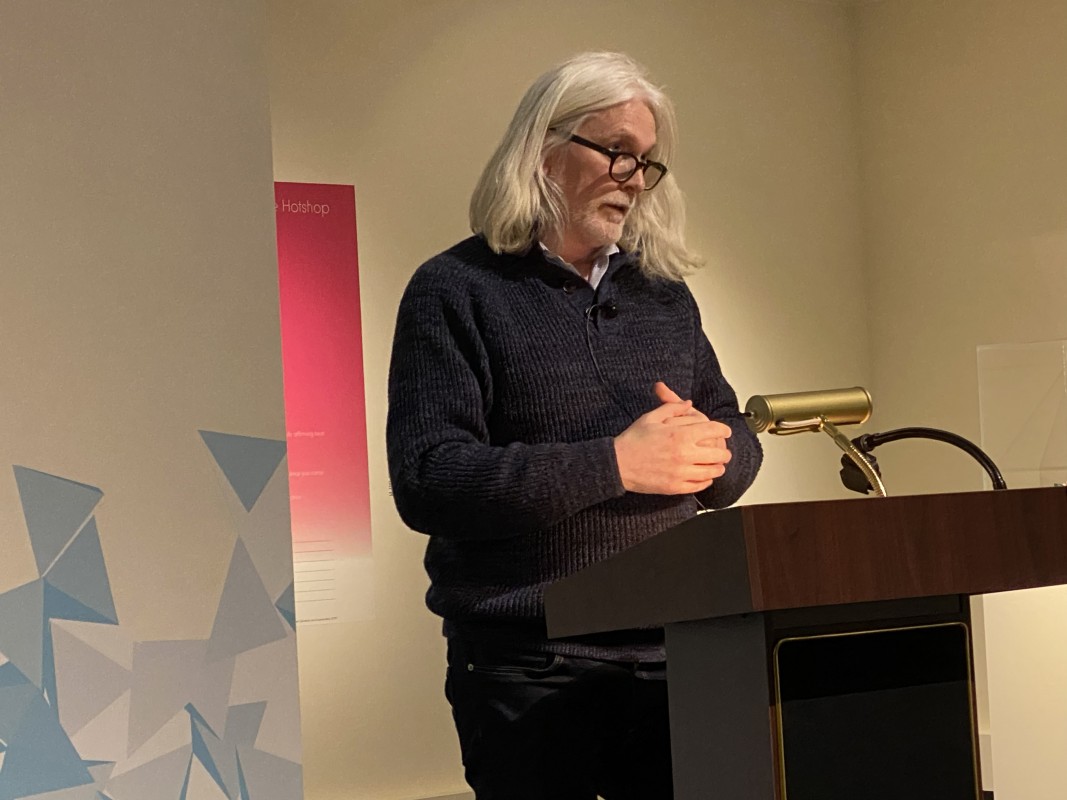

Professor of Art History Tom McDonough delivers the 2023 Harpur Dean’s Distinguished Lecture on the late art professor

Five months after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, sculptor and activist Ed Wilson stood before a Black activist group in Binghamton, driven to continue the civil rights leader’s work.

“What must we do to make white people realize that we are humans?” he asked the crowd.

During the decade that followed, it’s a question the African American artist sought to answer in his own large-scale, public work. Wilson, the founder of Harpur College’s studio art program, was the focus of the 2023 Harpur Dean’s Distinguished Lecture, presented on April 25 by Art History Professor Tom McDonough. His talk, “Black Monument: Ed Wilson Shapes African American History into Public Art, 1972-1984” focused on a series of artworks that Wilson created for libraries and schools in the Midwest and along the East Coast.

The art historian has presented Wilson’s work before: In 2019, he curated the exhibition “not but nothing other: African-American Portrayals, 1930 to Today,” for the Binghamton University Art Museum. In September, the museum will present the exhibition “Ed Wilson: The Sculptor as Afro-Humanist,” bringing fresh attention to the artist who taught at Binghamton for more than three decades.

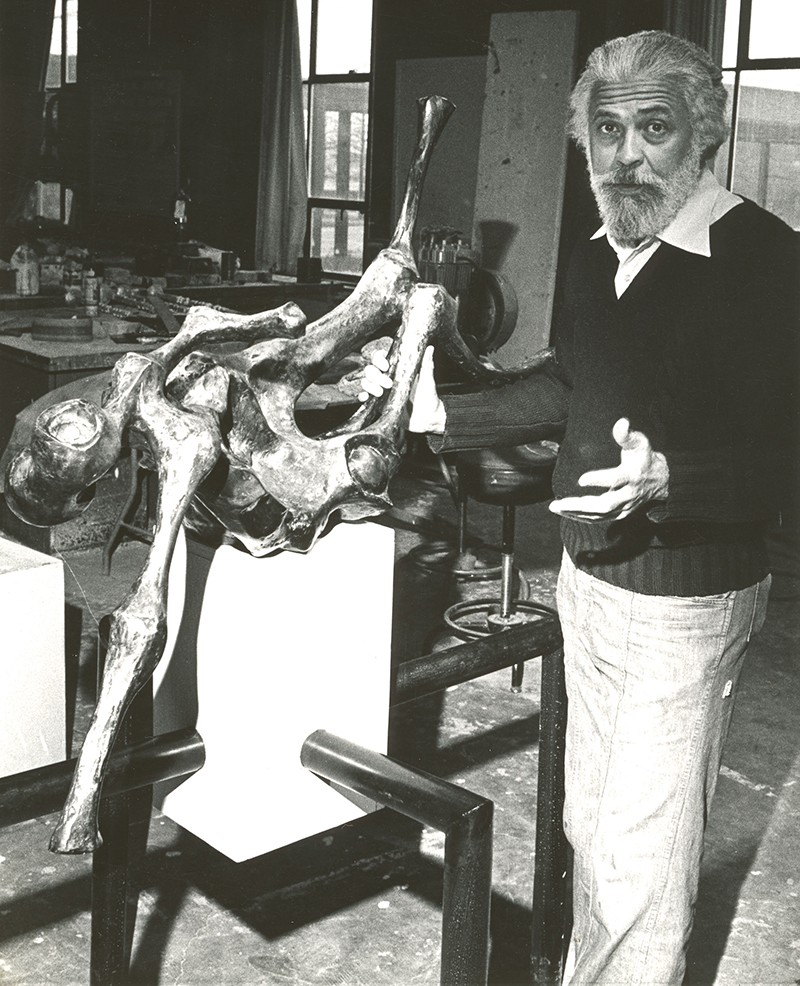

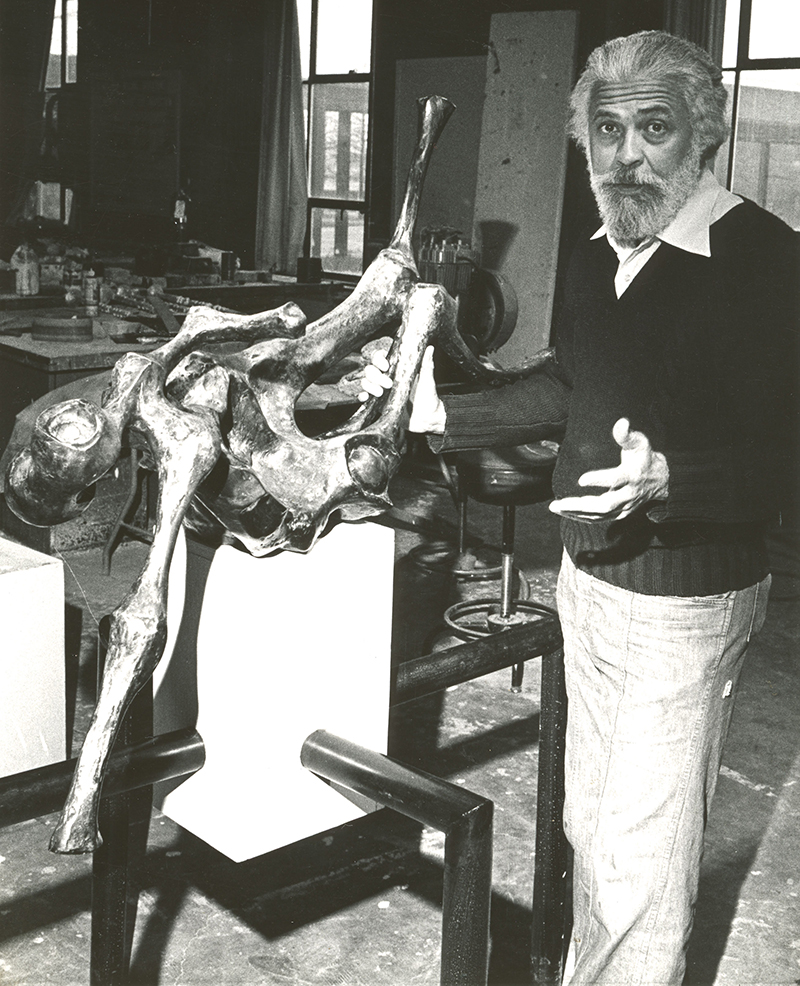

In the early 1970s, Wilson abandoned modernist abstraction and turned his attention to the history and culture of the Black American experience, inaugurating what would be the most productive decade of his career.

McDonough set the stage: In 1969, Binghamton’s student newspaper included a letter from a white faculty member in the Philosophy Department, protesting plans to institute an Africana Studies program. It would, the writer argued, “be another manifestation of racist thinking,” teaching Black students to ground their sense of self-worth in their racial identity rather than aspiring to what he called the “universal values of human excellence.” The author also railed against the hiring of Black student advisors for the same reason.

“Such tortured logic has unfortunately once again become familiar in our own day, regurgitated by white nationalists and their allies, who argue that the very acknowledgement of racism itself perpetuates racial categories, and that any attempt to recognize the specificity of Black experience be taken as a fundamental threat to the very social fabric of the country,” McDonough reflected.

Wilson, who joined Harpur in 1964 and became a full professor in 1967, responded to that letter via the Evening Press, the local daily newspaper. He questioned the myth of Western superiority that underlay these ideas, and the lack of a Black contribution to the Western thought showcased in the educational system except in imperialistic, paternalistic or racist terms.

As Wilson pointed out in the Evening Press, the Black experience had been invisible — a reality showcased in African American author Ralph Ellison’s famous work, The Invisible Man.

Wilson — who was commissioned in 1974 to create a sculpture of Ellison for a new library on Oklahoma City’s East Side — addressed that invisibility in his 1970s art. The steel-and-bronze sculpture at the Ralph Ellison Library featured two segments: On the right, a portrait of Ellison in profile, outdoors and with a seemingly sunny disposition. On the left, the native Oklahoman peered pensively from a shadowy oval bowl in the stainless steel surface.

“Aesthetically, he increasingly moved beyond the rather opaque, modernist allegories of alienation that have characterized his work of the 1960s,” McDonough said of Wilson’s 1970s work. “Politically, in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, he embraced a more radical understanding of the American politics of race. Together, these developments lead to new themes, and a search for new audiences in his work.”

Art and Black experience

Wilson first became involved in activism in North Carolina in the early 1960s, where he joined the Congress of Racial Equality in supporting sit-ins and desegregation efforts. After arriving at Binghamton in 1964, he served as faculty advisor to the campus Civil Rights Club and was active in the antiwar movement, McDonough said.

King’s April 1968 assassination marked a turning point. Wilson eulogized King at solidarity marches, and spoke about the civil rights leader’s legacy with students, local civic groups and activists. The murder compelled Wilson to consider the nation’s history of racialized violence, traced back through time to slavery, the Civil War and the genocide of Indigenous peoples, McDonough said.

That summer, Wilson used a $1,500 faculty research fellowship to spend two months in Harlem, sketching street life and planning what he called “a relief sculpture of the ghetto.” African-inspired fashions and natural hair were on the rise during that period, a departure from the integrationist tendencies of Wilson’s own generation.

“There in the context of the rise of the Black Power movement, he found a pervasive search for identity and drive toward self-determination,” McDonough said. “These experiences profoundly marked his understanding of white America’s relation to blackness.”

In the early 1970s, New York City was planning the new Boys and Girls High School in the predominantly Black Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in Brooklyn. As part of the planning process, the Board of Education hired African American painter Ernest Crichlow, a Brooklyn native and an influential figure in the Harlem Renaissance, as a consultant for a program that brought work by Black artists to the school. Wilson’s work Middle Passage, dedicated in 1977, was among them.

Placed outside the school entryway, Middle Passage consists of three curved concrete walls, positioned to form narrow passageways that mimic the conditions of a slave ship. Each wall featured bronze reliefs depicting the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade.

“This was his most ambitious foray into what we might call an environmental conception of sculpture, one in which the bodies of the viewers become fully implicated,” McDonough said.

Middle Passage is a work of memory. In 1995 and 1996, Wilson began another such work: Up From Slavery, which borrowed its name from Booker T. Washington’s autobiography. The clay model showed a vast allegorical tableau, representing rural labor, the Great Migration north and urban life, alongside innumerable dead buried in the ground. Wilson died in November 1996, before he was able to complete the sculpture.

Wilson recognized jazz as a model for Black artistic aspiration, translating Black experience into the language of art. That was reflected in the 1984 work Jazz Musicians, a bronze frieze he created for his alma mater: Frederick Douglass High School in Baltimore. The sculpture depicted a five-man jazz band in mid-performance, showing multiple images of each man to capture their dynamic motion.

Vastly different was an homage to Duke Ellington that he proposed for the Bartle Library in 1981, a year before work began on the Baltimore frieze. Never realized, the Binghamton proposal was highly abstract, based on the strings and hammers inside a piano, Ellington’s signature instrument.

“Wilson’s art represents another response to counter the monuments of white supremacy with ones that attest to the humanity, creativity and perseverance of Black America in public art for a Black audience, and a refusal to see Black culture in all its particularities as any less universal than the dominant one,” McDonough said.