Community Schools program connects districts with campus resources

College of Community and Public Affairs plays key role in BUCS

Debra Welsh-Clarke knows what it’s like to be a student with a disadvantaged background. The Brooklyn native was raised in a single-parent home and was going to join the Marines after high school until a mentor encouraged her to apply to some colleges first. After navigating the first-generation college student experience, she graduated from Binghamton University in 1994 with a bachelor’s degree in applied social science.

Welsh-Clarke was working with youth in midtown Manhattan when the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks took place and she saw social workers in action: “They had the credentials to work with the whole family system. I was intrigued with that and no longer wanted to just work with youth but expand into working with the whole family.”

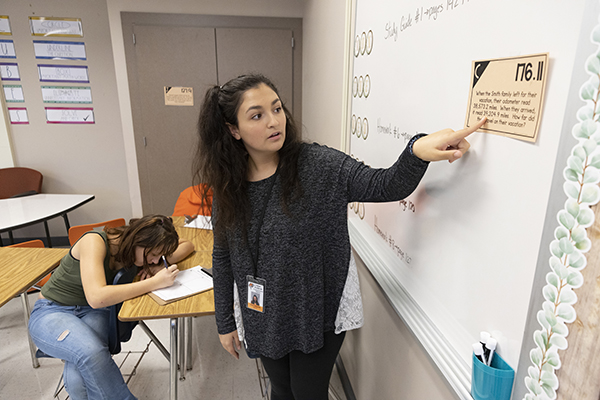

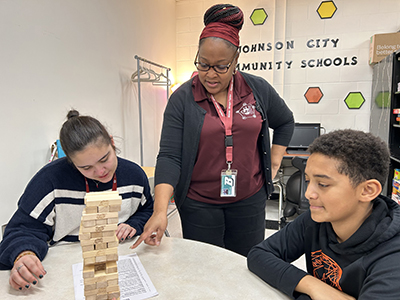

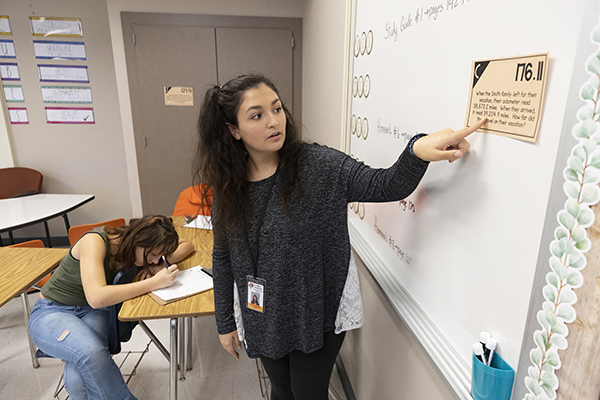

She returned to Binghamton and completed her master’s degree in social work in 2015 as a non-traditional student while raising two young children. After serving as a school social worker for several years, Welsh-Clarke was hired a year ago for her “dream job”: a community school coordinator for the Johnson City Central School District through the Binghamton University Community Schools (BUCS) program.

“We are making a difference for families every day through community schools,” she says. “We’re reaching a population that doesn’t feel like they have the support of knowing how to navigate the system. We’re opening up opportunities for students and families to access life-changing services. We empower those who might not know their potential and show them what they can accomplish.”

About community schools

More than 25 million students in America’s public schools live in under-resourced households — the highest proportion in generations, according to the National Education Association. Many students come to school hungry or face unstable housing situations, which can make it difficult to attend school, much less be ready and excited to learn. That’s where community schools come into play: They focus on what students in their community need in order to succeed.

By partnering with local nonprofits and the public and private sector, schools can bring tailored services into their buildings, such as free, healthy meals; healthcare; and tutoring or mental health counseling, before, during and after school hours. The goal is to combat intergenerational poverty and create educational equity for all students, which leads to improved student learning, stronger families and healthier communities.

“The community school model helps to raise an entire community,” says Laura Bronstein, dean of the College of Community and Public Affairs (CCPA). “All children and youth should be able to be successful in school, to graduate and then become productive members of society.”

A university assist

The community school model has long inspired Bronstein, and she has overseen the development of the first-ever, county-wide, university-assisted community school network focusing on districts in small cities and rural communities. Binghamton University Community Schools officially became an entity in 2018. During its evolution, it has not only received millions of dollars in federal, state and local grants, but it has garnered attention from institutions such as the University of Pennsylvania and Stanford and Duke universities, in addition to the Council of Chief State School Officers, among others.

“This program can be adopted by other universities, where it can support both local communities as well as today’s college students who are eager to make a difference in the world,” Bronstein says.

BUCS is a partnership among CCPA, Binghamton University’s Center for Civic Engagement and local school districts, providing opportunities for nearly 500 University students to volunteer and intern with local youth and families each year. Ongoing opportunities include tutoring, lunchtime engagement, bully prevention programs, parent and family engagement, access to health and social services, and event-based volunteerism. Some Binghamton faculty projects include asthma education, youth financial literacy, maker’s spaces, an archeology after-school program and telemental health services. Many Binghamton alumni work in BUCS’ administration offices and as community school coordinators in the area schools.

“BUCS has helped to connect the brilliance of our faculty and students with local districts,” says Luann Kida ’01, MA ’03, BUCS’ executive director. “We are a conduit that helps the spider web come together. We’re all partnering for the betterment of our youth.”

In the 2022-23 school year, BUCS’ Regional Network supports nine local districts, 44 school buildings, four Broome-Tioga Board of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES) sites and 21 community school coordinators — all serving about 17,000 pre-K to 12th-grade students.

“The needs are different in every district you’re in,” says Maddie DeLoria-Mancini, a community school coordinator in the Windsor Central School District. “We are here to support families in any capacity, whether that’s clothing, food, case management or connecting parents to resources. We will help and point them in the right direction.”

The Endicott, N.Y., native received her bachelor’s degree in psychology from SUNY Oswego in 2018 and her master’s degree in social work from Binghamton University in 2020.

“My first real exposure to community schools was during my graduate studies when I helped manage the drop-in center at Whitney Point High School,” DeLoria-Mancini says. “We provided social and emotional support throughout the school day to 15 to 20 students at a time. They were looking for support for things going on at home, as well as anxiety or depression.”

An early district partner

Whitney Point Central School District was one of the earliest partners in what would eventually become BUCS. In 2009, Binghamton University, BOCES and Lourdes Health Care won a federal Safe Schools – Healthy Students grant, a county-wide initiative to connect services within the community to address school climate, substance abuse and youth violence.

That same year, Master of Social Work Fellows began supporting schools through that grant, becoming the first county-wide coordinated placement.

“I don’t believe we would be as far as we are in reaching desired outcomes if we didn’t have the support of Binghamton University,” says Patricia A. Follette, MSEd ’94, EdD ’19, who served as the superintendent of the Whitney Point Central School District from 2012-21. “Through the University, all community school coordinators have access to the same professional development and resources so they can support and guide the regional schools instead of each school trying to do it all independently.”

Coming full circle

Christine Merton’s introduction to community schools was during her first-year graduate-student internship, also at Whitney Point.

“I saw the power of home visits, meeting families where they are at,” says the South Glens Falls, N.Y., native who earned her psychology degree from SUNY Oneonta and graduated from Binghamton University in 2015 with a master’s degree in social work.

“It was really about building relationships with families and their students, and we recognized that it was an honor that the families were welcoming us into their lives,” she says.

Home visits where she heard about barriers to transportation, literacy struggles and food or clothing insecurities provided a way for Merton to understand that community schools truly “support families by whatever means,” she says.

After graduation, Merton first worked at a nonprofit, which showed her how much the educational system impacts youth and families.

“I realized that if you really want to help students and families, you have to be proactive instead of reactive,” she says. “And now, more than ever since the pandemic, schools aren’t just a place to educate. Schools are the hub of our communities.”

Merton recently became a school social worker at Vestal Central School District, and began her role as the community school coordinator this past summer when the district signed on to participate with BUCS.

“I learned from Luann Kida and have watched the program grow from afar for the past 10 years, and now I’m beginning the work in Vestal,” Merton says. “It’s a full-circle moment.”