Could a smartphone app help prevent falls in older adults?

Researchers at Binghamton University's Motion Analysis Research Laboratory study balance, develop app to help older adults

Most adults who find themselves in their golden years quickly realize that their overall ability to maintain balance isn’t what it used to be. One out of every four adults ages 65 and up in the United States are likely to suffer from a fall, the leading cause of fatal and nonfatal injuries in that age group.

But they don’t have to be — and a Binghamton University study has been working to prevent falls, using something found in nearly every person’s pocket.

“We can use a phone not just for evaluation, but for delivering intervention. In this case, we can ask somebody to stand still with the phone in their pocket, or record standing while looking straight ahead. The phone itself will use accelerometers to see how much body sway is happening,” said Vipul Lugade, an associate professor of physical therapy and one of the co-principal investigators of this study. “The scale is tiny. We can actually look at this amount of movement and figure out how stable the person is while standing.”

Lugade earned his master’s and doctoral degrees in human physiology and biomechanics from the University of Oregon. He also completed a postdoctoral fellowship in rehabilitation and body-worn monitoring at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and held a position as an independent scholar in Chiang Mai, Thailand. At Binghamton, he is the director of the Motion Analysis Research Laboratory (MARL), where the first step of this research into older adult fall risk prevention using smartphones was recently completed.

“As you get older, you need to be aware of your body’s ability to maintain balance while standing and walking,” Lugade said. “The ability to do two tasks at the same time is compromised as you get older. Older adults have an inability to either allocate attention to both tasks simultaneously or have an inability to switch between tasks.”

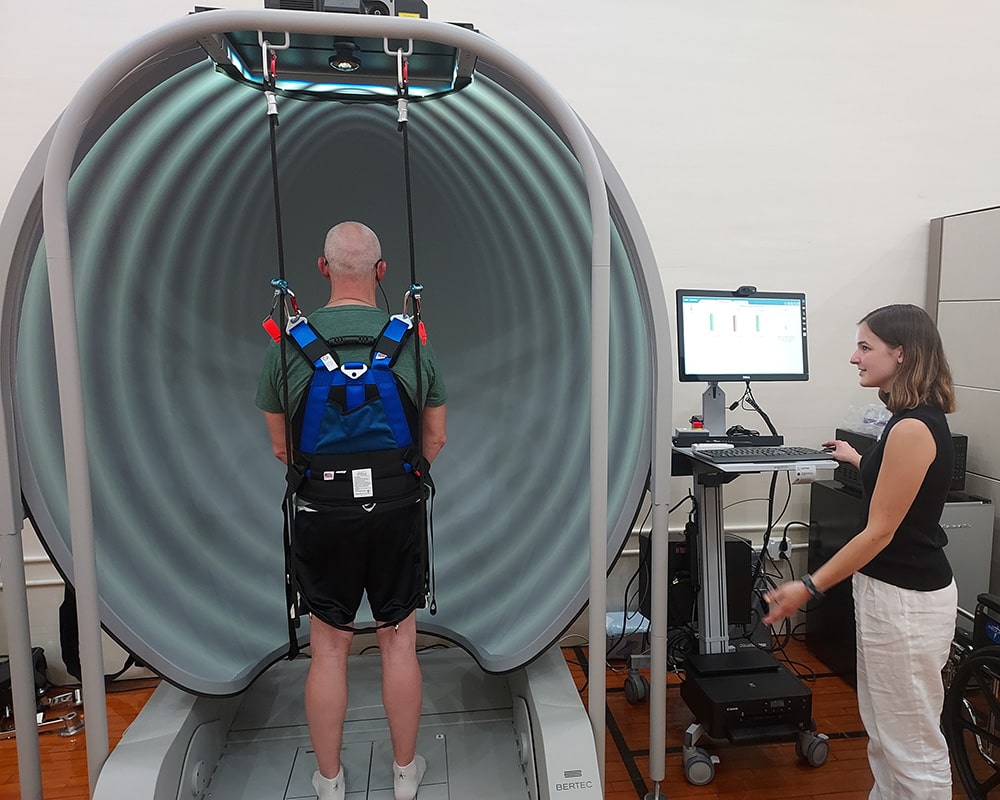

The MARL intervention study began in June 2022 and set out to investigate some of these issues. Among the cutting-edge equipment in the lab is a 12-camera motion analysis system, a Biodex System Dynamometer (for individual muscle rehabilitation), a Portable GAITRite System (electronic walkway for measurement) and eye-tracking glasses.

Most important in this study is a Computerized Dynamic Posturography (CDP) system, which measures “postural sway” by analyzing foot pressure, force and motor reactions while the user stands in a harness on a locked or moving platform.

Using this specialized motion-capture gear, researchers looked at gait speed and balance. Improvements, in gait speed especially, have been shown to reduce the risk of falls; if individuals show an improvement after utilizing the smartphone-based program, the intervention could be seen as clinically effective.

This is helpful, as the main goal for this stage of research is to find out if the smartphone app they’ve developed is even a usable tool in helping older adults with balance-related deficiencies. By completing regular exercise programs and weekly balance evaluations at home, are these participants getting everything they can out of the program — and is it an improvement or even a change from a paper version of the test?

Out of the 31 participants who were involved, 29 older adults completed all the exercises and tests and were reevaluated at the end of the study. This high completion rate showed virtually no difference in the electronic vs. paper applications.

“The app is a viable alternative to paper and can be safely used to deliver balance interventions to a person’s phone,” said Suzanne O’Brien, the second co-principal investigator and an associate professor of physical therapy. “We want to take some next steps to use the app to deliver exercises and prevent falls in older adults in this [rural] area. Later on, we’d like to do the same in some patient groups, such as Parkinson’s Disease and stroke.”

O’Brien completed her master’s degree in neurologic physical therapy from the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia and a doctorate in health practice research from the University of Rochester School of Nursing. She is well equipped to attend to all matters regarding the study, but in this case, also served an additional function.

Due to its “double-blind” set-up — which means the researchers did not know if a participant was part of the paper or electronic groups or their overall testing results, and the participants were unaware of the opposing group they were designated to — O’Brien and Lugade each knew only partial aspects of the results prior to the completion of the study. This helped reduce bias in the sample group and prevented the researchers from unduly influencing the results.

“Lowering the chance of bias strengthens the possibility that our results are accurate, or the results happened only because of the intervention, and not our behavior,” O’Brien said. “When an intervention study finds that the intervention yielded an outcome, then we can say that the intervention caused the outcome, and this is highly desirable in research.”

Connecting with the participants was also an important aspect of the study. A separate measurement included the likelihood and happiness of individuals in completing the app-based practice. To this end, O’Brien completed weekly phone check-ins during the four-week study, and testers were in the room during all in-office visits to ensure participant safety.

Patima Silsupadol, an assistant professor of physical therapy who received her master’s and doctoral degrees in human physiology (motor control) from the University of Oregon, and Molly Torbitt, PhD ’23, a graduate student who completed her doctorate in physical therapy at Nazareth College of Rochester (who has since earned a PhD in community research and action from Binghamton and become an assistant professor in the Department of Physical Therapy Education, College of Health Professions at Upstate Medical University in Syracuse), were the testers who worked directly with the participants.

Both Silsupadol and Torbitt reported that the participants were pleased to be involved in the study.

“Some were extremely excited, talkative and motivated to start the exercise program. They were also mostly enthusiastic about being part of the study and learning more about their own balance,” Silsupadol said. “They enjoyed the motion analysis tasks and even would take out their personal cameras/phones to take pictures of themselves in the reflective markers!”

Although some participants indicated experiencing physical and mentally fatigue as well as muscle soreness from the exercises and tests, the overall study found that seniors were capable of using the smartphone app and that its development could be a boon to patient balance and well-being.

The researchers in this study, however, weren’t content with just collecting this data. Their secondary goal is to ensure that what they collected can now be used by the community in addition to the physicians and individuals who can benefit from the interventions.

Along with Lijun Yin, a professor of computer science at Binghamton, the team has started working on a computer dashboard that looks at performance metrics and compares the users with the “normal” range. The long-term idea would be to collect data nationwide so that the user could compare via demographics like age and gender; clinicians across the country could use the model to focus on results across their patient set to provide the best care possible, and someday may even be able to push updates automatically — from real-time records of the patient’s results, and adjusted to performance.

The team has obtained seed grants from the Binghamton University Transdisciplinary Areas of Excellence-Data Science to continue this work, and has applied for external funding, including one from the National Institutes of Health. They hope in the next steps of the project to modify certain aspects for more accurate results: for example, by increasing sample size, or using some of the funding to address potential participants from underrepresented communities who may need the interventions but don’t have access to smartphones.

Meanwhile, the team is excited to have completed the first step in a process that serves to help a set of people at high risk who are often disregarded or seen as fragile. Torbitt, one of the first to join the MARL, looks forward to future research across the country by academic institutions like Binghamton.

“When I started in the lab in January 2022, myself and Vipul, along with a few undergraduate students, were working to get the equipment functioning and creating manuals so that research efforts like these could take place for years to come,” she said. “Being able to see where we started in [June] 2022 to following through on a study of this magnitude was incredibly fulfilling. I am proud to have been a part of this study and think that the effects of it will benefit older adults in ways I never thought possible.”