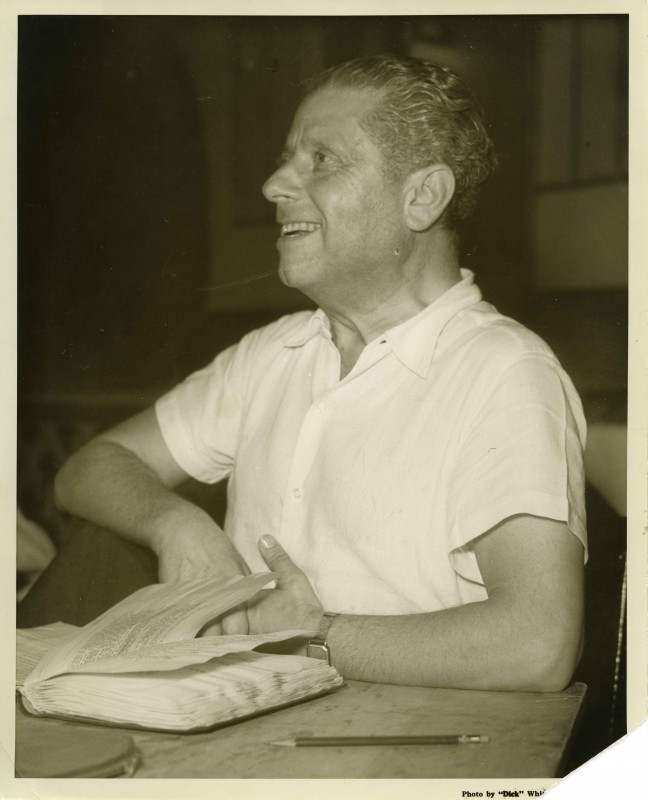

Center stage: Project will transcribe famed director’s promptbook

A partnership between Binghamton and a German university centers on Max Reinhardt and his 1920 staging of a scandalous play

If Reigen were published today, it would probably be optioned by HBO.

Translated into English as “La Ronde,” the name of a round dance, Arthur Schnitzler’s play centers on 10 pairs of characters and their interlinking sexual relationships. That’s common enough fare on the screen now, but its racy content created a firestorm back in its day. In fact, the Austrian playwright originally circulated it only among his friends until its publication in 1903, and it wasn’t brought to the stage until 1920 by famed Austrian director Max Reinhardt.

“It caused an immense scandal, which had to do with a number of factors: obviously the sex, but also the rising anti-Semitism of the early years of the Weimer Republic,” said Associate Professor of German and Russian Studies Neil Christian Pages.

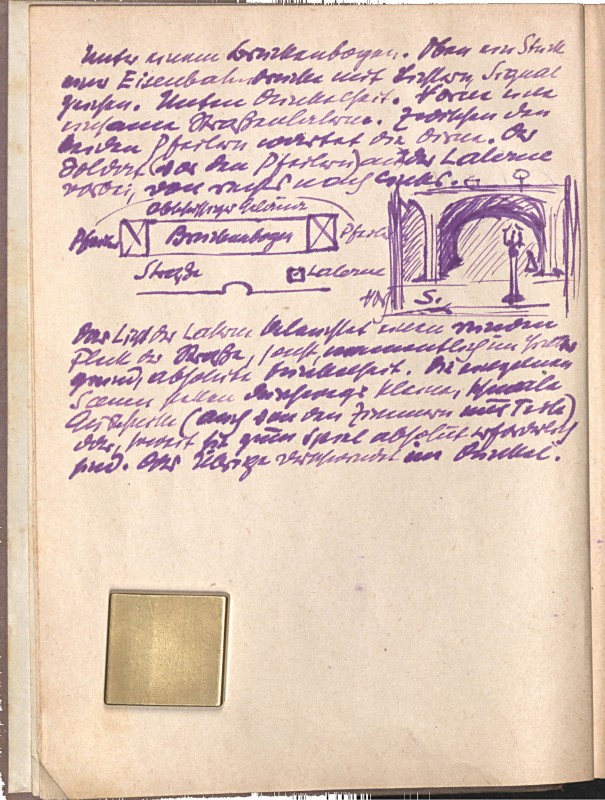

Reinhardt’s promptbook — an annotated copy of a play used by a prompter during a performance — still exists and is part of the Binghamton University Libraries’ Special Collections. Dieter Martin at the University of Freiburg received a 75,000 Euro grant from a federal German research initiative to transcribe and annotate the digitized promptbook and make it available to a wider audience.

The project will also include an international conference at Binghamton and a website where researchers, students and teachers can access the digital scholarship.

“This is a treasure of literary and cultural history, and not just for people who happen to be interested in German Studies,” said Associate Professor of German Carl Gelderloos. “People around the world are interested in this object.”

Schnitzler was a well-known figure who frequently centered his often-controversial plays on love, sex and relationships, along with clever dialogue. Reigen was no exception.

A cultural legacy

“Think of Hollywood Squares; this is how you could stage it,” Pages reflected. “There’s the housewife, the chambermaid, the baron, the rich CEO, the baker, the guy who owns the hardware store and the secretary, and they all have sex with each other, like a Virginia reel.”

Reinhardt decided to stage the play at one of the dozen theaters he owned in Berlin. While the promptbook includes handwritten notes on how he wants the play staged, the busy director essentially set up the production and left it to one of his assistants to oversee.

The play proved scandalous for Schnitzler, who was called a “Jewish pornographer.” However, the uproar propelled Reigen into the public imagination; it has seen multiple film adaptions through the decades.

How did the promptbook end up at Binghamton? Reinhardt fled Nazi Germany in 1933, as did many Jewish people working in theater or cinema, who then became involved in Hollywood’s Golden Age. The script’s complicated backstory even involved Marilyn Monroe at one point; she had recognized Reinhardt’s promptbooks and purchased them at an auction, and then ended up selling them to Reinhardt’s son, Gottfried.

The Reigen promptbook, along with the majority of the items in the Max Reinhardt Archives and Library, was acquired by the University’s Theatre department in the late 1960s from Gottfried. A decade later it was transferred into the custody of the Libraries’ Special Collections, which to this day welcomes in-person visitors and addresses dozens of email queries each year in reference to the internationally acclaimed collection of promptbooks, manuscripts, correspondence, photographs, theater programs, scrapbooks, publications, objects and artwork. The collection has benefitted from other grant-funded digital projects in the past, including one from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation to digitize the 132 original Reinhardt promptbooks in Binghamton’s holdings.

“We have a long tradition of exiles teaching here. This is where the Arthur Schnitzler Research Association was started, which is today the journal Austrian Studies,” Pages said.

In April, researchers from the University of Freiburg will be on campus to view the original manuscript and check it against the digital copy. While it looks deceptively simple, digital philology of this sort is resource-intensive, Pages said. Reinhardt’s handwritten notes in the text will be transcribed, translated and made available to scholars.

“One of the university’s tasks is to maintain and cultivate the things that were left to us as our inheritance from the people who came before us,” Pages said. “The Max Reinhardt archive is part of our cultural legacy.”