How a decades-old friendship helped Binghamton researchers create the first dissociative steroidal anti-inflammatory drug

For those living with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) their fight just got a little easier.

HOPE IS A POWERFUL THING.

For those living in fear or pain due to a debilitating disease, the hope of a treatment can motivate them to keep fighting. For those living with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a common genetic disease that mostly affects young boys, their fight just got a little easier.

In October, a new drug called AGAMREE® (vamorolone), developed by researchers from the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, received Food and Drug Administration (FDA), European Medicines Association (EU) and Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (UK) approval for the treatment of patients with DMD. Kanneboyina Nagaraju, professor of pharmaceutical sciences and dean of the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences; and Associate Dean for Research and Research Development Eric Hoffman have spent over 15 years developing vamorolone.

“Vamorolone is the first dissociative steroidal drug able to separate the benefit of the glucocorticoid class of drugs from some of the key side effects, such as bone and growth disturbances associated with these drugs,” Nagaraju says. “My laboratory tested vamorolone in mouse models of DMD over 10 years ago, and this provided the pre-clinical data to advance the drug to human trials.”

THE FIGHT AGAINST DMD

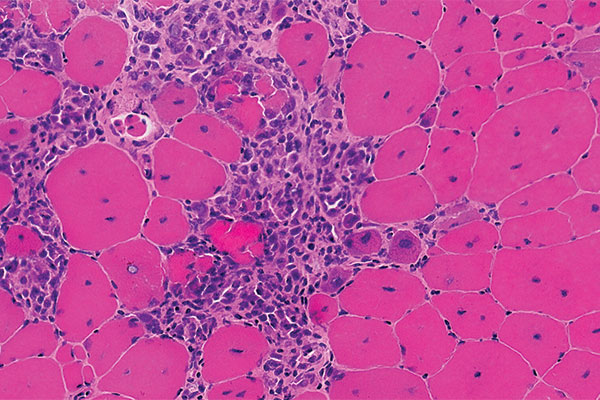

DMD is a genetic disease affecting about one in 3,500-5,000 male newborns worldwide. Because it decreases dystrophin protein in muscle tissues, it creates progressive weakness and challenges in everyday life. The DMD gene is the largest in the human genome, spanning 2.3 million base pairs (letters of DNA code) on the X chromosome. Most young boys are affected because the gene is on the X chromosome.

“DMD is the most common genetic muscle disease worldwide, and I have been working on translational research on DMD since 1985,” Hoffman says. “To enable robust clinical trials in DMD, I established the Cooperative International Neuromuscular Research Group (CINRG), and vamorolone became one of the first drugs tested by the CINRG international clinical trial network.”

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 121 boys with DMD, ages 4 to less than 7 years, vamorolone increased strength and mobility relative to a placebo, and reduced side effects relative to prednisone.

Nagaraju and Hoffman have collaborated in this venture since joining forces 18 years ago at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Together with medicinal chemist John McCall, they launched the spin-off company ReveraGen BioPharma to take vamorolone through the drug development pathway.

“I originally proposed vamorolone as a membrane stabilizer to counter-act dystrophin deficiency in DMD patient muscle,” says McCall, president for chemistry at ReveraGen. “As Raju, Eric and I learned more and more about vamorolone, we found it to be a dissociative steroid with multiple new structure/activity relationships compared to traditional glucocorticoid anti-inflammatories and a strong candidate for moving into DMD clinical trials.”

A CLOSE BOND

While the collaboration between Nagaraju, Hoffman and McCall sparked the scientific breakthrough we’re talking about today, it wouldn’t have been possible if not for a simple cassette tape almost 30 years ago.

“Eric is the kindest human I’ve ever met,” Nagaraju says. “When I came to the United States in 1995, I worked at the National Institutes of Health, and one of my lab mates gave me this cassette. He said ‘You might want to listen to this,’ and it was a keynote lecture of this guy named Eric Hoffman.” That was the first time Nagaraju heard Hoffman.

“Then in 1999, Eric was giving a presentation on gene expression profiling. I made sure to go see him and introduce myself. He was genuinely interested in talking to me and learning more about the work I was doing at the time. I ended up giving him a ride home and we started talking a lot about our work and getting to know each other more.”

In 2005, the pair ended up working together when Hoffman asked Nagaraju to join him at Children’s National Medical Center he recalls. “I am an immunologist. I had never worked on Duchenne muscular dystrophy. I knew quite a lot about it, but I had never actually done any research on it, but Eric trusted me and knew what I was capable of. That meant the world to me.”

Since then, the two have formed a close bond. Their families spend time together, they have in-depth conversations on just about every topic, and, of course, they find time to make scientific discoveries.

“I feel very honored and privileged to have Raju as a long-term research collaborator and friend,” Hoffman says. “His deep scientific knowledge and his rigorous approach to experimental design and interpretation has brought great strength and international impact to our collaborative work over the decades. To work so closely with someone you have such complete trust and respect for, while together effectively working to get so many things accomplished for those living with DMD (vamorolone included) and their families, is just a wonderful thing.”

The researchers also had another key partner cheering them on: the young patients with DMD and their parents.

“They had hope that we were developing something that would do what we said it would,” Hoffman says. “Families with DMD were involved in the design and management of the vamorolone program from day one. It wouldn’t have been possible without them because they had hope that spurred us on.

As scientists, we want to make sure we’re not creating false hope for patients. So it is the issue of hope versus false hope sometimes. And I believe, at the end of the day, we have worked with the families and international medical research community to deliver a new therapy for all those living with DMD.”