Wired for addiction

Drugs can erode impulse control

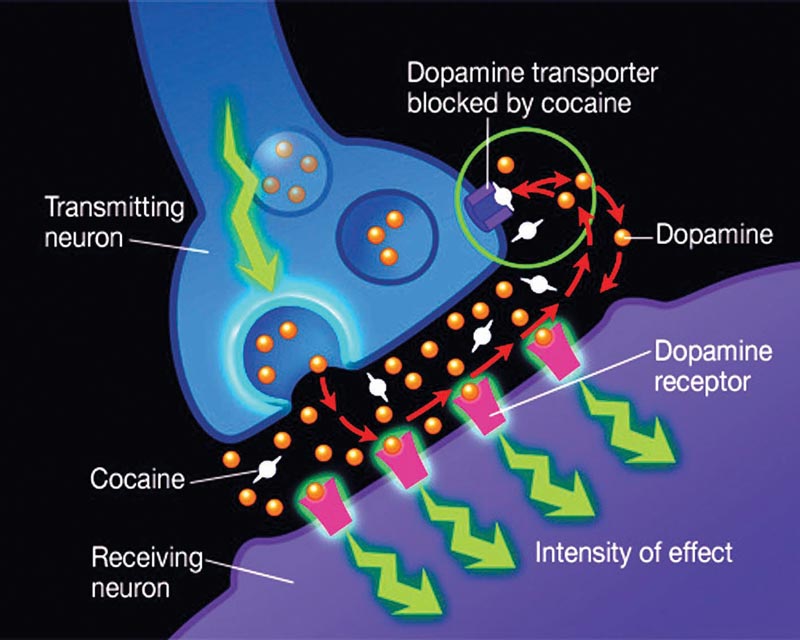

In 1997, Time magazine’s cover story on addiction was headlined: “Why do people get hooked? Mounting evidence points to a powerful brain chemical called dopamine.” Dopamine had left the lab and entered the public consciousness. It was big news in addiction research because scientists had concluded that illicit drugs get you “high” by triggering a rush of dopamine into the reward pathways of the brain.

J. David Jentsch was a graduate student in neurobiology at Yale University at the time, researching psychosis. His research revealed changes in brain chemistry caused by drugs of abuse, but not the kind that get you high. These changes were occurring in the parts of the brain that let you stop yourself from getting high, or eating another cookie or stealing.

The theory that a disruption of the impulse-control circuit might be implicated in addiction began to take shape. “It was a bit of a radical idea,” Jentsch says. “Before we even started the research, my colleague and I had published a paper proposing the idea, and it’s become a pretty significant work in the field.

“Neuroscientists spent a lot of time trying to figure out why we like drugs. But nobody had studied why, even though we like drugs, we choose not to take them and we stop ourselves from doing that.

“I started thinking about that and never stopped,” he says.

Not all users become addicts

A 2011 statistic from the National Institute on Drug Abuse says that of 4.2 million Americans who had used heroin at least once, an estimated 23 percent of them became dependent on it.

“That tells us that in many cases the drug is not sufficient to break the brain. Rather, there is a subset of people more vulnerable to the effects of the drug,” says Jentsch, Binghamton University professor of psychology. He has spent more than 20 years investigating impulsivity as a critical marker of a person’s vulnerability to addiction.

This isn’t “just-say-no” impulse control; this is at the molecular level. Some key findings from Jentsch’s research:

- Drugs of abuse can cause chemical changes in the frontal lobe and basal ganglia — specifically a loss of dopamine D2-type receptors — that result in erosion of impulse control.

- Even before drug abuse begins, an individual’s impulse-control abilities predict his or her subsequent propensity to initiate and escalate drug taking.

- Individual differences (most likely genetic) present before drug abuse begins to set people on different trajectories. People whose dopamine D2-type receptors and impulse control are low at baseline find drugs more rewarding than do people whose dopamine D2-type receptors and impulse control abilities are high.

Jentsch is now looking for specific genes and brain systems that trigger impulsivity and resulting susceptibility to addictions.

Though these genes are a significant factor for vulnerability, so are environment (home life) and development (age at first drug use, for example). The interaction of the three creates loops of cause and effect. “Some people can enter this loop and their circuitry is resilient enough that it doesn’t spiral out of control; for others it’s a very different trajectory.

“If you grow up in an environment where illegal drugs are not something you can easily come by, the chances you are going to become a drug addict are relatively low. Drug addiction rates in the Amish are very low for a reason. It’s not because they have better genes, it’s because they have a better environment,” he says.

“My belief is that we’ll find a common set of genetic factors that erode the integrity of this impulse-control circuitry, and it just gets manifested in different ways in different people.”

A path to prevention

Jentsch’s goal is not to cure addiction, but to prevent it. An impulsive statement? Not coming from him. “My impulse control works too well. I went to a casino once, and in five minutes I was bored. I went to the hospital for pain, and they’re giving me intravenous opiates and I get no reward from them at all,” he says, laughing.

Prevention is within the grasp of science because of rapidly evolving technology and a more sophisticated way of thinking about the problem of addiction, he says. “It’s enabling progress that was just never possible before.

“If we can get a handle on what it means to be genetically, environmentally and developmentally vulnerable, and identify the brain pathways that represent vulnerability, then we can develop scientifically sound evidence on how to medically intervene,” he says.

It might involve a blood test that can assess a person’s risk. Treatment might be medication or education.

“Genetic discrimination is potentially a very big problem. But I think that although there are reasonable ethical questions about proceeding down this line, there are also reasonable ethical questions about not doing this. Because this disorder is going to continue to afflict people and continue to take lives, and we have an ethical obligation to do what we can. That’s where I see this work going and why I increasingly focus on the idea of predicting vulnerability as opposed to waiting for the process to play out and then trying to undo the effects of addiction.”