Fateful legacy

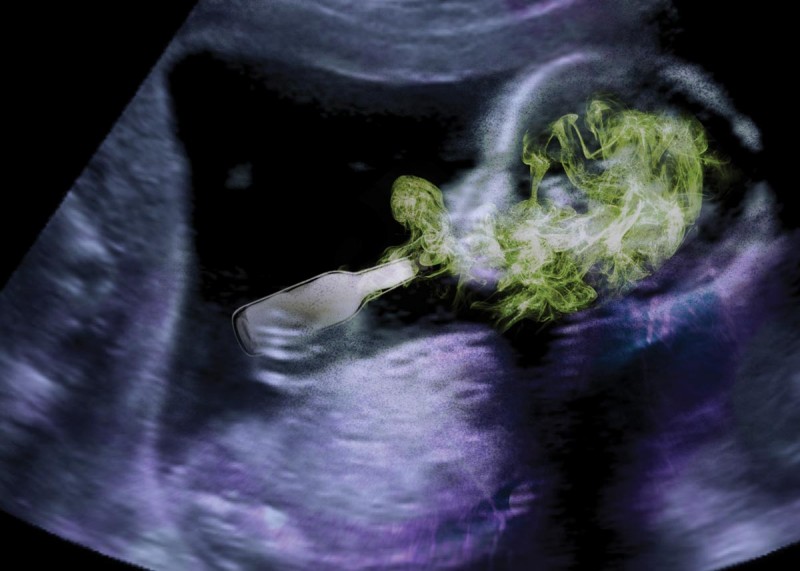

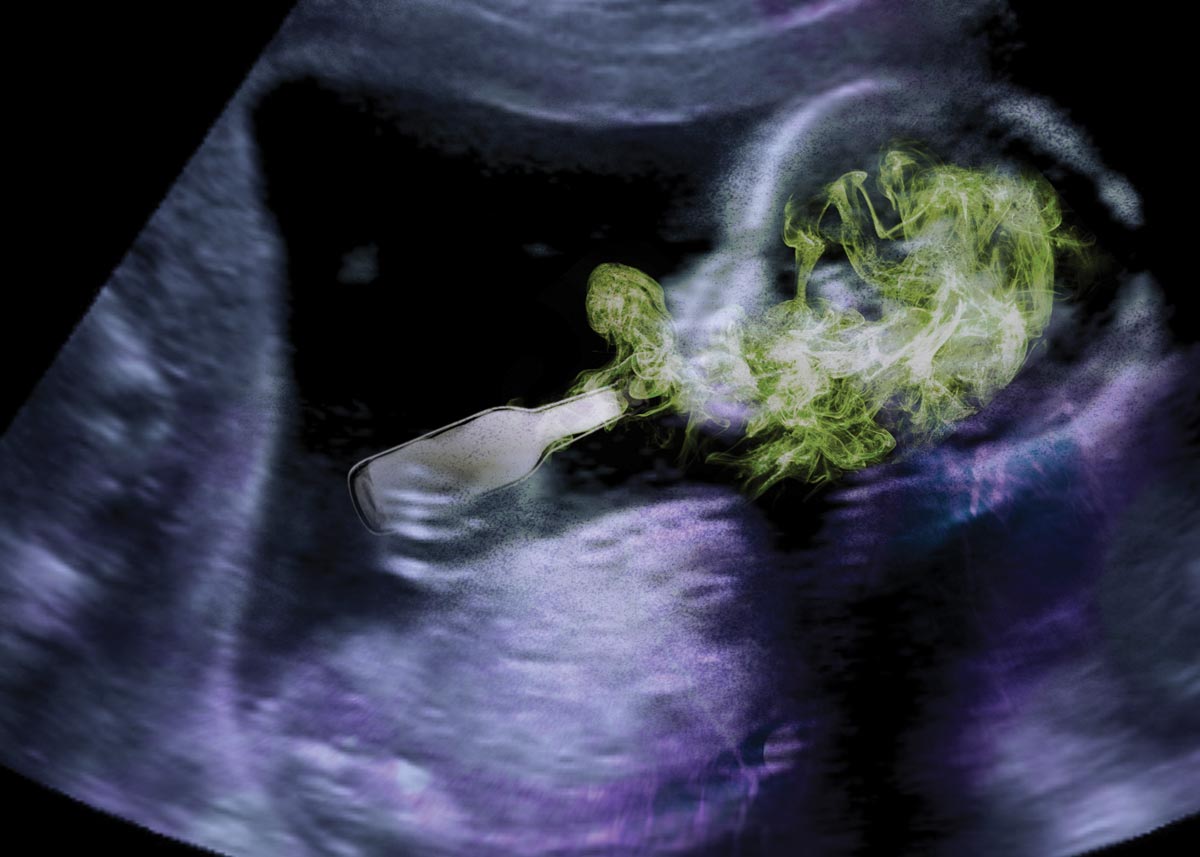

Drinking while pregnant can harm future grandchildren

When a pregnant woman drinks alcohol, so does her baby, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Now a study shows that a pregnant mother who drinks isn’t harming just her unborn child but her future grandchildren as well.

A team of researchers led by Nicole Cameron, assistant professor of psychology at Binghamton University, was the first to show that alcohol consumption during pregnancy can have an effect on future generations, even if they are not prenatally exposed to alcohol.

Pregnant rats received the equivalent of one glass of wine, four days in a row, at the gestational equivalent of the second trimester in humans. A control group received water. When the second-generation offspring were offered alcohol or water, the rats that had been exposed to alcohol in utero showed a preference for alcohol. Third-generation rats from the alcohol exposure line continued to show a preference for alcohol over water.

“Our findings show that in the rat, when a mother consumes the equivalent of one glass of wine four times during the pregnancy, her offspring and grand-offspring, up to the third generation, show increased alcohol preference and less sensitivity to alcohol,” Cameron says. “Thus, the offspring are more likely to develop alcoholism.”

If four drinks over four days can produce such obvious effects, what about just one binge?

Marvin Diaz, assistant professor of psychology, and Elena Varlinskaya, research professor, found that even one episode of drinking — enough to raise the mother’s blood-alcohol level to the legal definition of intoxication — can increase social anxiety-like behaviors in her offspring, from adolescence through adulthood.

“Surprisingly, we found that socially anxious rats (as a result of this binge-like prenatal alcohol exposure) actually exhibit decreased anxiety in tests of more generalized anxietylike behaviors,” Diaz says.

In humans, a socially anxious person declines a party invitation in order to avoid a crowd. A person with a low level of general anxiety can sometimes seem fearless.

“Based on our findings, prenatal alcohol exposure appears to both increase risk-taking behaviors while also making one nervous in social situations,” Diaz says. “We believe that this sort of behavior may lead to increased alcohol consumption (which reduces anxiety) particularly during experiences that bring on anxiety (social situations).

“We are actually in the process of testing this very question.”

So what, exactly, is alcohol doing to developing brains to cause the behaviors that Binghamton researchers are observing?

Yao-Ying Ma, assistant professor of psychology, thinks “silent synapses” might reveal some answers.

Synapses carry signals between neurons. During fetal development, the newly generated synapses are immature and relay no information between neurons; they are “silent synapses.” Within three weeks after birth, the synapses either mature — become functional — via recruiting proteins, called AMPA receptors, or they are pruned.

Ma hypothesizes that prenatal alcohol exposure derails the maturation/pruning processes by replacing healthy AMPA receptors with atypical ones.

“If this is the case, we will try to disable these atypical AMPA receptors to restore normal synapses,” she says. Work will be done in her lab.

Because prenatal alcohol exposure is a known risk factor for drug use, Ma expects that rats bred with that risk factor will show less inclination to self-administer cocaine once the atypical AMPA receptors are disabled.

This is the first time the concept of silent synapses will be introduced into alcohol studies, Ma says. “I’ve always focused on addiction, but previously it was illegal drugs like cocaine and opiates. I’m happy to switch to something legal because more people are exposed to this.”