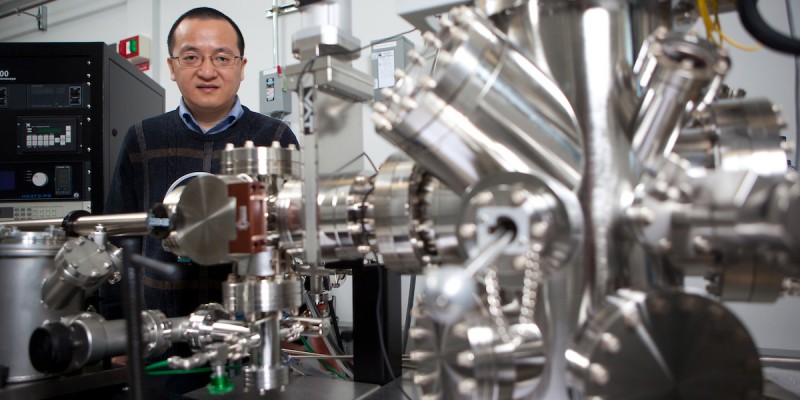

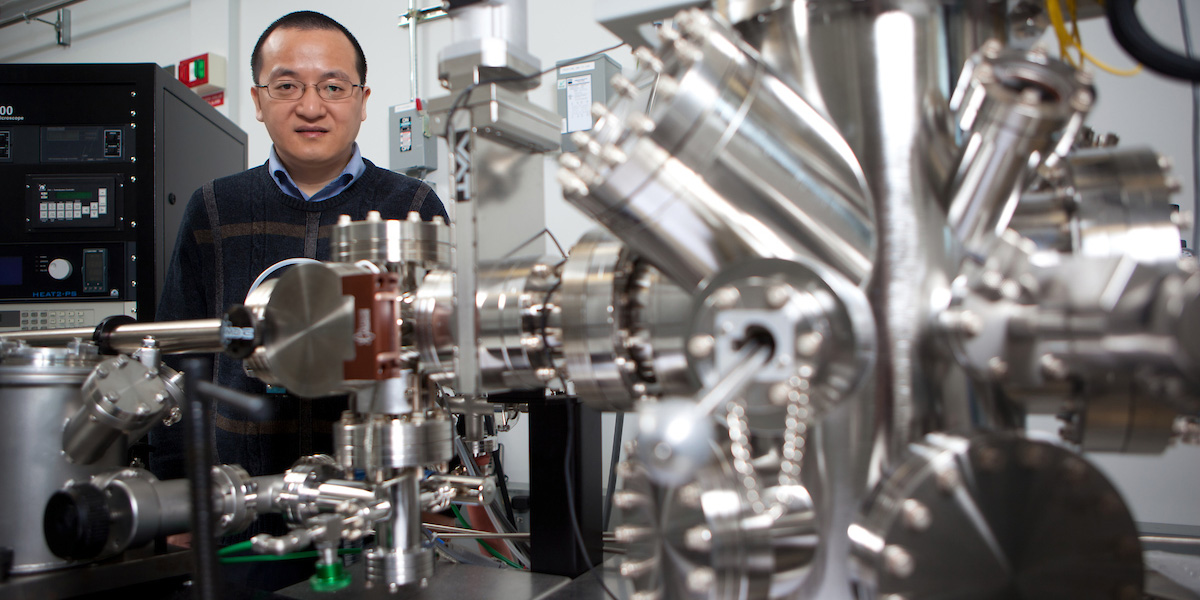

Watson College professor named fellow of Microscopy Society of America for materials research

SUNY Distinguished Professor Guangwen Zhou has been using electron microscopy to study atomic structures for nearly three decades

The tiniest particles comprising everything we know look like black dots under a transmission electron microscope (TEM).

TEMs beam electrons around the speed of light through extremely thin samples, magnifying them as much as 50 million times to reveal new worlds we cannot see with our naked eye. The resulting images of atomic structures are captured by specialized cameras that can snap over 3,000 frames per second.

SUNY Distinguished Professor Guangwen Zhou first saw a TEM when he was a graduate student. A traditional instrument, he said, nearly scrapes the lab ceiling at about 3 meters high.

“The machine is so big, but what you see is actually so small. That’s a sharp contrast,” he said. “It feels really exciting to use such a big machine to look at such a small-scale structure.”

Since his student days, Zhou has garnered more than 11,000 citations according to Google Scholar, been named one of the world’s top researchers in his field by Stanford University and published more than 260 papers in peer-reviewed journals like Nature and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Most recently, Zhou was named a fellow of the Microscopy Society of America (MSA) for his “outstanding research using in-situ environmental transmission electron microscopy, advancing dynamic understanding of surface and interface reactions in harsh conditions.”

“This recognition is the culmination of [Professor Zhou’s] many years of outstanding research and highlights the high esteem by which he is held by his colleagues and peers,” Mechanical Engineering Department Chair Paul Chiarot said.

This title is reserved for no more than 0.5% of all MSA members each year, recognizing senior society members who made significant contributions to the field of microscopy and microanalysis, according to MSA.

“It’s an honor and also a privilege to be a fellow,” Zhou said. “If you look at the current fellows, they are very established people. For my own work, I get a lot of help from my colleagues and the University, and I have a lot of collaborators at the Brookhaven National Lab.”

That 18-year partnership has allowed Zhou to use state-of-the-art equipment to observe never-before-seen reactions, including the oxidation process of metals at atomic scales.

Novel techniques on an old instrument

Most times, TEM is used to observe static samples, which is where you’d find constellations of black dots on the microscope screen. What Zhou and his team do differently, however, is they make in situ observations — essentially, introducing external stimuli like heat and pressure in order to watch atoms dance, jump and change phases in real time, a feat once thought to be impossible.

“Let’s say we have a tiny sample. You can actually heat it up to a high temperature, and you can also introduce it to some reactive gas, like oxygen or water vapor and so on,” Zhou said. “You can see that reaction. That’s how we use this tool to study the dynamic behavior of materials.”

By understanding how the atomic fabric of metals morphs and degrades under extreme conditions, scientists can begin to solve real-world engineering conundrums. Zhou’s work could make sturdier metal alloys that live up to their full potential strength or find ways to slow corrosion and save money on machine and device repairs.

“How can I control the composition and maybe also the microstructure? With this fundamental research, maybe we can have some better ideas on how to design stainless steel and make it last longer,” he said.

With the TEM, Zhou’s lab can also probe minute defects in atomic structure, tiny details which can make all the difference in the overall strength and behavior of materials.

“[Professor Zhou’s] outstanding research, particularly in in situ environmental transmission electron microscopy and its impact on understanding surface and interface reactions in harsh conditions, has set a high standard in his field,” said Atul Kelkar, dean of the Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science.

Labs like machine shops

Learning how to work this tool so deftly was no easy feat. Zhou recalled the very first thing he learned about the TEM was not how to operate the instrument itself, but rather how to make samples.

There’s nothing to see, after all, without a well-prepared sample. But how do you cut a bulky hunk of steel into a sheet less than 100 nanometers thick, thin enough for electrons to pass through?

When Zhou started out, the answer was a painstaking process involving sawing off a piece of metal, sometimes with a chainsaw, then mechanically crushing it, polishing it and thinning it. Sometimes it took a day to make a single sample.

“You can think about people working in a machine shop, or something similar like that,” he said.

Even after finally loading the sample into the instrument, the work wasn’t over. When Zhou was a graduate student, there were no special cameras capable of capturing thousands of frames each second, tracking every movement of a wayward atom.

Rather, Zhou and fellow students had to use negative films, exposing them to electron beams then later developing them in a dark room to observe what now is easily transmitted to a computer.

“It took a lot of time to learn how to use the microscope, but once you have a good sample and you see something interesting, you feel excited,” he recalled. “Because that’s kind of a reward for the labor.”

Solving real-world problems

Zhou’s research has yielded promising results, such as by demonstrating how oxygen can play a role in forming protective layers against further corrosion and how hydrogen can replace more carbon-intensive manufacturing processes in the steel industry.

“Down the road, I think there’s still a lot of exciting opportunities for a lot of unknown questions,” he said. “For research, you always push the envelope. You want to go further.”

We are years past the days when samples had to be prepared by hand. Students nowadays don’t know that process, Zhou remarked with a laugh, but he still tries to maintain the same core principles with everyone who passes through his lab and classroom doors — some of whom have now become faculty members themselves.

“I always tell my students to not only just look at the beautiful images. You have to look at the mechanism behind the images,” he said, something he has now seen replicated in his students’ publications as they establish their own careers.

But even after almost 30 years in the field, the sight of those black dots comprising the most fundamental makeup of existence never gets old.

“You can feel some excitement when you really, actually work on the microscope and see something that I think many people may never have seen before,” Zhou said. “Each sample is unique, so when you visualize it under the microscope, you always get some unique features. It keeps your curiosity on this.”