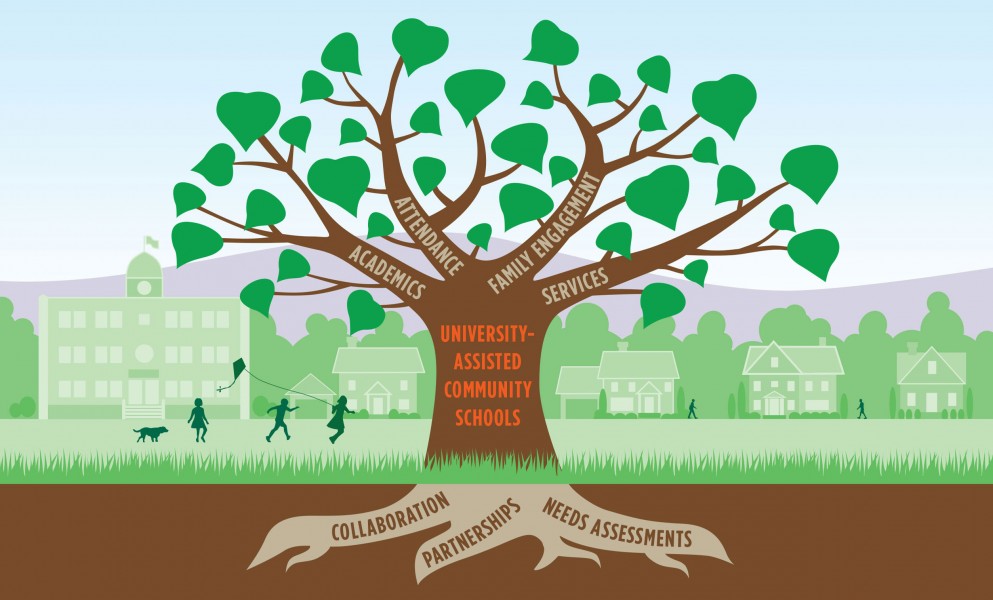

Whole child, whole school, whole community

Integrated initiatives through partnerships and research impact schools

Binghamton University’s partnership with school districts offering “community schools” has grown in size and scope, helping researchers study how severe stress impacts the ability of children to learn.

“The role of universities is changing; we are expected to be more active partners,” says Elizabeth Anderson, associate professor of education, who studied effects of trauma and toxic stress in a local elementary school. Trauma and toxic stress (a result of frequent or prolonged adversity) can change the brain’s development, contributing to deficits in attention, problem-solving and decision-making, and can lead to discipline problems.

“In recent years, Binghamton University has integrated its civic engagement efforts within the community and educational systems as a partner in several new initiatives, including trauma-informed approaches in schools,” she adds.

The community schools model (implemented through a program called the Broome County Promise Zone and now in also Elmira schools) offers an array of resources to support children and their families. The Promise Zone — a collaboration among the University, Broome County Mental Health Department and Broome-Tioga BOCES — grew from five school districts to seven in the 2016–17 academic year. The two new districts are in Chemung County. The program has served more than 1,000 children and 450 families.

The community schools model is enhanced through connecting University researchers to principals and teachers who work with the Promise Zone, says Luann Kida, MA ’03, community schools director of the Broome County Promise Zone and Binghamton University Community Schools.

“Researchers regularly seek out the Promise Zone to help them build upon existing relationships to conduct their studies with children, teachers and educational practices,” says Kida.

Anderson says it’s important for educators to think about how challenging circumstances can impact children.

“I encourage my graduate-education students to think about the whole child,” she says. “This intersection of academics, mental health and health offers a more holistic approach to meeting today’s children’s needs.”

Separating school and stress

In addition to her graduate students, Anderson wants to help teachers and school personnel think differently about how to approach challenging situations.

She co-authored a paper with Associate Professor of Social Work Lisa Blitz and master of social work student Monique Saastamoinen ’15 in the journal Urban Review last year. The paper shows how university-school partnerships can help address trauma and toxic stress.

The research, conducted at a local elementary school, shows that abuse and neglect contribute to trauma and toxic stress, Blitz says. Children who live in financially poor communities are often exposed to more crime, violence and other factors that impact them negatively.

“The problem is not poverty per se, but children who live in neighborhoods with high poverty are more likely to be exposed to loss, painful events and adverse circumstances. Children carry this pain, yet there are no classroom techniques for teachers to address this trauma,” Blitz says.

Blitz believes all school personnel should understand the physiological effects of trauma.

“Through our research, we learned that school personnel are aware of the adversity the children in their classrooms face, but they weren’t necessarily making the connection between this adversity and student behavior,” Blitz says. “Some teachers made the connection but simply didn’t feel equipped to respond to students’ mental health needs.”

“My social work colleagues bring an important perspective to teachers on how trauma, toxic stress and social-cultural-economic factors can impact children’s behavior at school,” Anderson says.

Johnson City has implemented new training based on the trauma-informed approaches from the study.

“There are several districts implementing the trauma research,” Kida says. “Understanding how to deal with trauma and toxic stress has become a core aspect of professional development for teachers in the Johnson City school district.”

Kida says the community schools coordinators collaborate with Binghamton faculty on other research.

“Professors say there’s a learning curve when they work in schools that don’t have the support of [the Promise Zone] staff, who are taught to think of everything from reserving room space to publicizing an event,” she says. “This is the holistic community schools training that I think the faculty really benefit from.”

Anderson thinks Binghamton is gaining traction in the community schools movement.

“Our institution is seen as an important community partner in helping to meet the increasingly complex needs of today’s children by helping to pioneer this nationally-renowned educational model in the Southern Tier.”