Self-powered sensors could increase life span of knee implants

Assistant professor Sherry Towfighian received a grant from the National Institutes of Health to begin work on a smart implant that could drastically reduce the number of knee replacement surgeries.

Knee replacement surgery is one of the most common bone surgeries in the United States, yet the average implant will only last about five years. Increasingly, this surgery is being performed for younger, more active patients who are faced with a dilemma. When they undergo the surgery, they are expected to remain physically active for their overall health, but that activity can also wear down the new implant. Often, doctors don’t know if patients are overexerting themselves until they begin to develop symptoms. By that point, the damage to the implant has already been done. For a young patient, going through knee replacement surgery every five years is a daunting task, but finding the perfect balance of activity levels to maintain the integrity of the implant has been equally daunting.

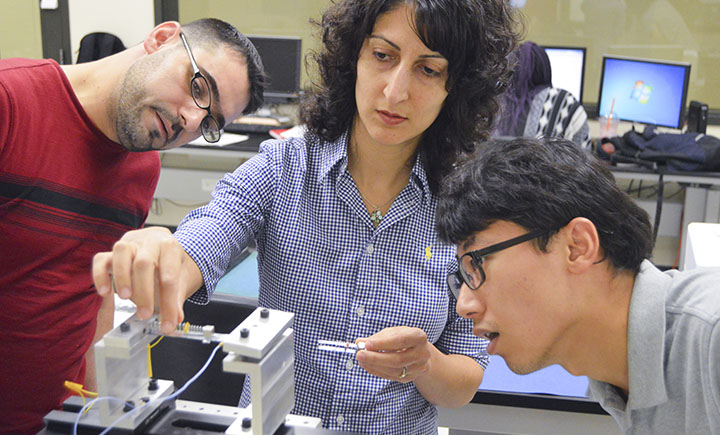

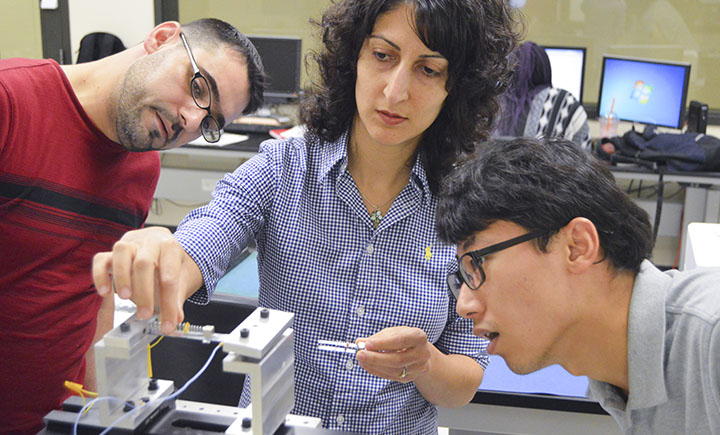

Assistant professor Sherry Towfighian from the Thomas J. Watson School of Engineering and Applied Science is working on a solution. She is the lead principle investigator on a study titled “An implantable self-powered load sensor for total knee replacement health monitoring” along with other principle investigators Ryan Willing from Western University and Emre Salman from Stony Brook University. The study recently received a grant of more than $200,000 from the National Institutes of Health.

The proposal involves the creation of a unique type of implant with sensors that can monitor activity. “The implant will be able to tell doctors when a patient has exerted too much pressure before the symptoms start to show up,” said Towfighian. “If the doctor is able to adjust the patient’s activity levels before there is damage, the implant will last much longer than the typical five years.”

These smart implants will not only give feedback to doctors, but will help researchers like Towfighian in the development of future implants. “The sensors will tell us more about the demands that are placed on implants. With that knowledge, we can start to improve the implants even more,” said Towfighian.

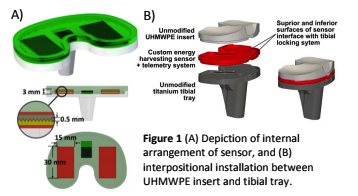

However, building the sensors into the implant is not enough to solve the problem. Towfighian explained that, “while sensors can help elongate the life of a knee implant, a battery-operated sensor would mean that doctors would still be faced with the need to perform regular surgeries to replace the battery.” That’s why the study won’t stop at just making an implant with sensors, it also aims to create one that can be self-powered.

The study will develop a way for the implant to use what is called triboelectric energy. The prefix tribo – Greek for rub — refers to friction and while the term triboelectric is fairly uncommon, almost everyone has some basic experience with it. “When you rub a balloon on your hair, that friction creates triboelectric energy. Knee joints do something similar when you walk or climb the stairs,” said Towfighian.

Towfighian is hopeful that the combination of activity sensors and a self-powered system will increase the life span of knee implants and reduce the need for follow-up surgeries. For young patients looking at the possibility of knee replacement surgery, this development has potential to be life changing.