New research finds cause of alloy weakness

For years, materials scientists have been perplexed by the question of why alloys don’t meet their full potential strength. A deep look at atomic patterns finds the answer.

Sometimes calculations don’t match reality. That’s the problem that has faced materials scientists for years when trying to determine the strength of alloys. There has been a disconnect between the theoretical strength of alloys and how strong they actually are. So, what has been missing?

New research has found the answer to this problem with a study done as a collaboration between researchers at Binghamton University, the University of Pittsburg, the University of Michigan and Brookhaven National Laboratory. The work was also supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Researchers used advanced technology to look at alloys on an atomic level in order to understand what has been affecting the strength and other properties.

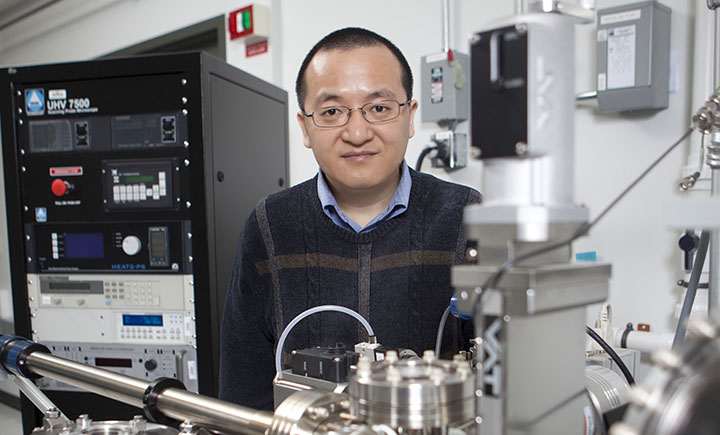

Binghamton University materials science and engineering professor Guangwen Zhou was one of the scientists working on the project.

Zhou and his team used a Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) for the study, a tool that has been around since 1935 and has evolved dramatically in recent years with the incorporation of aberration correction techniques and environmental capabilities. It’s powerful enough to look deep into the structure of atoms.

“We were able to observe that the changes in alloys from surface segregation were accompanied by the formation of dislocations in the subsurface,” explained Zhou. “Atoms typically make patterns, but when there’s a dislocation, that means the pattern has been interrupted.”

Dislocations are what make the alloys weaker than the theoretical calculations expect and Zhou’s research found that surface segregation is what leads to those dislocations.

“By understanding how the dislocation forms, we can start to control it,” said Zhou.

This could lead to strengthening a variety of alloys that are valued specifically for their strength and light weight.

This groundbreaking research provides insight into what needs to change in order to strengthen all kinds of alloys that are used in airplanes, jewelry, medical tools, bridges, cookware and a plethora of other common objects.

The study is titled “Dislocation nucleation facilitated by atomic segregation” and was recently published in Nature Materials.