Using fungi to fix bridges

Binghamton University researchers have been working on a self-healing concrete that uses a specific type of fungi as a healing agent.

America’s crumbling infrastructure has been a topic of ongoing discussion in political debates and campaign rallies. The problem of aging bridges and increasingly dangerous roads is one that has been well documented and there seems to be a consensus from both democrats and republicans that something must be done.

However, spending on infrastructure improvement has continually gone down. The New York Times reported in 2016, based on a report for the Bureau of Economic Analysis, that “in the 1950s and ’60s, federal, state and local governments were spending twice as much on the nation’s public infrastructure, relative to the size of the economy, as they are today.”

The hesitancy to invest in America’s infrastructure may come from a number of sources, but the fact remains that most want something to be done before the consequences are too severe.

Binghamton University assistant professor Congrui Jin has been working on this problem since 2013, and recently published her paper “Interactions of fungi with concrete: significant importance for bio-based self-healing concrete” in the academic journal Construction & Building Materials.

This research is the first application of fungi for self-healing concrete, a low-cost, pollution-free and sustainable approach.

Why is infrastructure crumbling?

Jin’s studies have looked specifically at concrete and found that the problem stems from the smallest of cracks in the concrete.

“Without proper treatment, cracks tend to progress further and eventually require costly repair,” said Jin. “If micro-cracks expand and reach the steel reinforcement, not only the concrete will be attacked, but also the reinforcement will be corroded, as it is exposed to water, oxygen, possibly CO2 and chlorides, leading to structural failure.”

These cracks can cause huge and sometimes unseen problems for infrastructure. One potentially critical example is the case of nuclear power plants that may use concrete for radiation shielding.

What can be done?

While remaking a structure would replace the aging concrete, this would only be a short-term fix until more cracks again spring up. Jin wanted to see if there was a way to fix the concrete permanently.

“This idea was originally inspired by the miraculous ability of the human body to heal itself of cuts, bruises and broken bones,” said Jin. “For the damaged skins and tissues, the host will take in nutrients that can produce new substitutes to heal the damaged parts.”

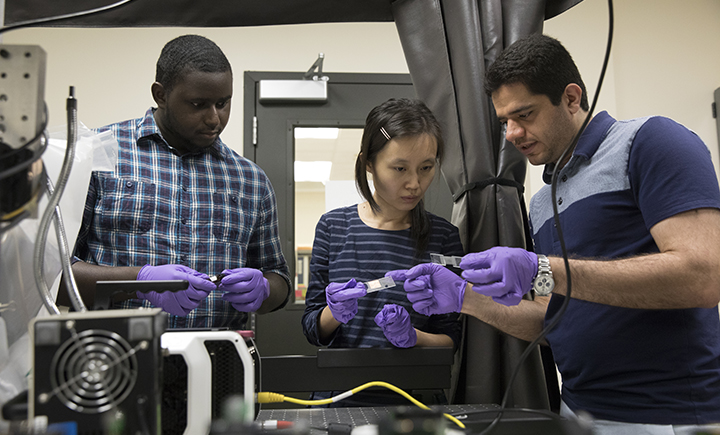

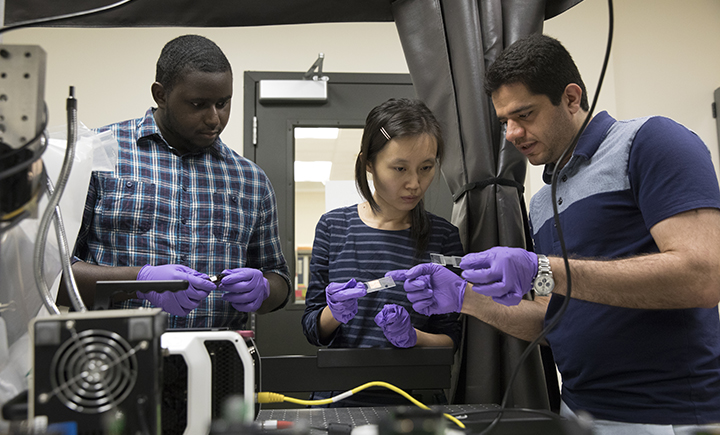

Jin worked with associate professor Ning Zhang from Rutgers University, and professor Guangwen Zhou and associate professor David Davies from Binghamton University with support from the Research Foundation for the State University of New York’s Sustainable Community Transdisciplinary Area of Excellence Program. Together, the team set out to find a way to heal concrete.

The team found an unusual answer, a fungus called Trichoderma reesei.

When this fungus is mixed with concrete, it originally lies dormant — until the first crack appears.

“The fungal spores, together with nutrients, will be placed into the concrete matrix during the mixing process. When cracking occurs, water and oxygen will find their way in. With enough water and oxygen, the dormant fungal spores will germinate, grow and precipitate calcium carbonate to heal the cracks,” explained Jin.

“When the cracks are completely filled and ultimately no more water or oxygen can enter inside, the fungi will again form spores. As the environmental conditions become favorable in later stages, the spores could be wakened again.”

The research is still in fairly early stages with the biggest issue being the survivability of the fungus within the harsh environment of concrete. However, Jin is hopeful that with further adjustments the Trichoderma reesei will be able to effectively fill the cracks.

“There are still significant challenges to bring an efficient self-healing product to the concrete market. In my opinion, further investigation in alternative microorganisms such as fungi and yeasts for the application of self-healing concrete becomes of great potential importance,” said Jin.