An Interview with Professor Emeritus Elizabeth Wichmann-Walczak of University of Hawai‘i

SONG Chenqing

SONG Chenqing (Interviewer): Professor Wichmann-Walczak, thank you very much for accepting the invitation for an interview from TheaComm. First, let me introduce myself. I am Chenqing Song, Associate Professor of Chinese Studies and Director of the Translation Research and Instruction Program (TRIP) at Binghamton University. For this interview, I have questions that I divided into a couple of topics. Which one would you like to do first? I have questions about your Jingju (Beijing opera) performance, teaching and training, and your translation and research on Jingju.

Elizabeth Wichmann-Walczak: However you would like to do it.

SONG Chenqing: Great. In a few sentences, please tell us a little more about your

general experience with Jingju. Could you please capture the highlights of your career related to Jingju?

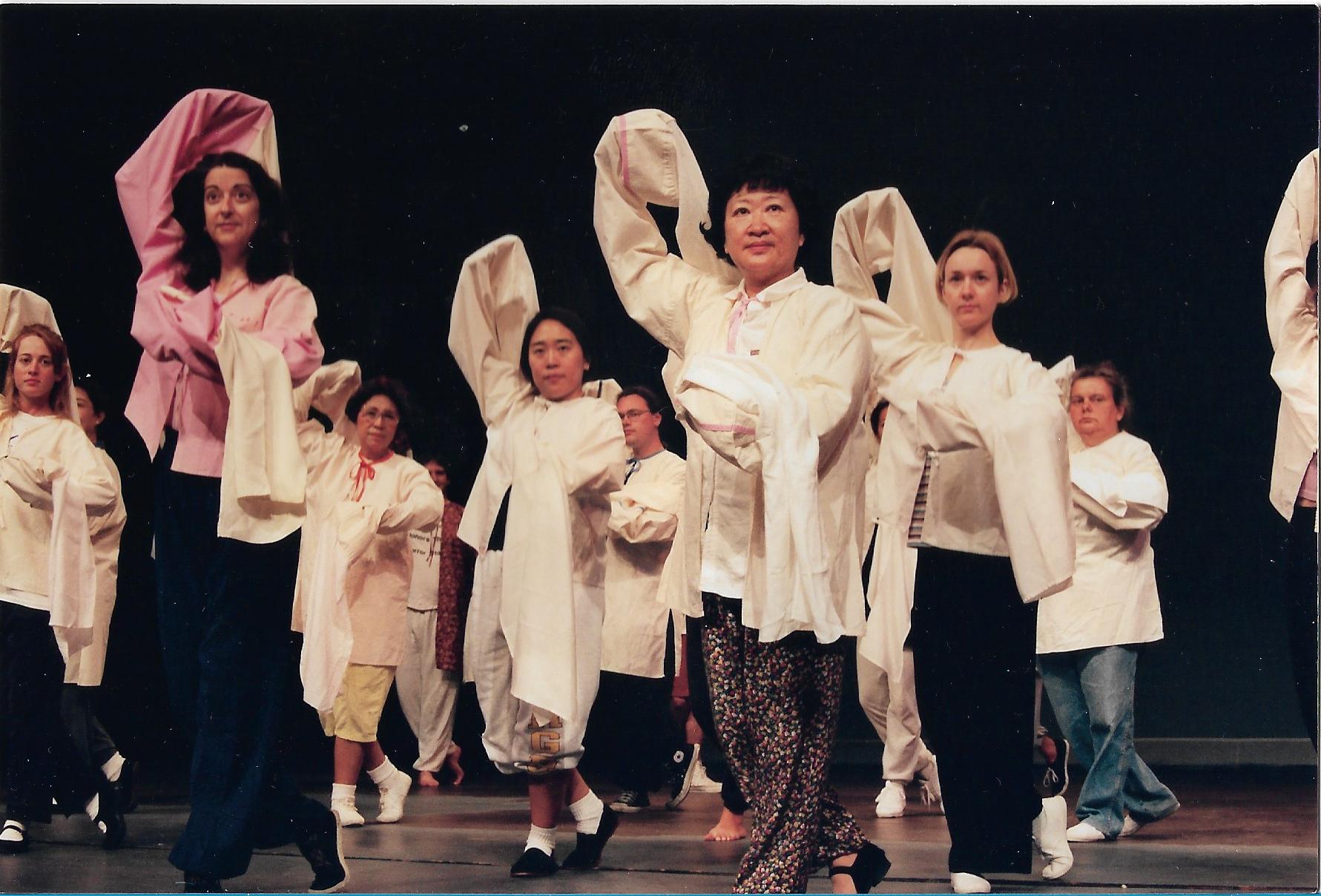

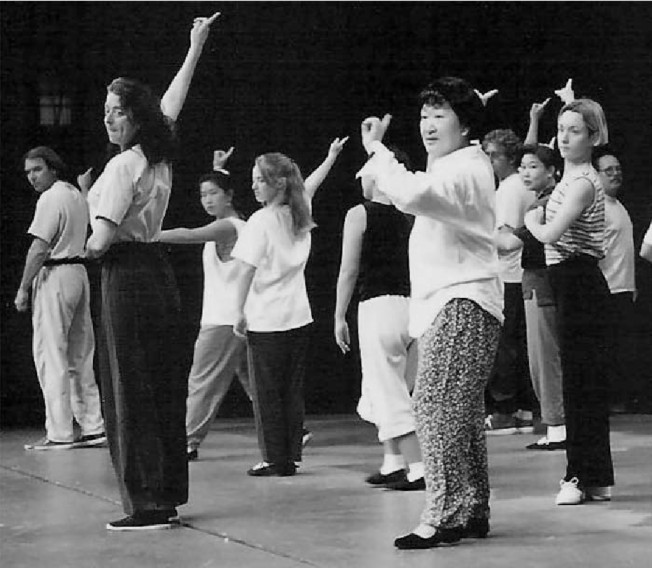

Elizabeth: I became aware of Jingju as an undergraduate in college. I was majoring in both theater and Chinese language, so it was pretty natural to put the two together. It became the focus of my research as a graduate student and then as a scholar at the University of Hawaii. Once on the faculty, I could bring Jingju artist-teachers from China to Hawaii to train our students to perform, including the orchestra and students in the music department. And to make this happen, I worked with the teachers to select a play, put together the script, and then it was my responsibility to translate it into performable English — English that could be performed as Jingju. And then there was lots of revision in the course of the teaching leading up to the performances, so all together in my almost four-decade career, I did this with nine different programs and ten different plays because the last performance was zhezixi (one-acts).

SONG Chenqing: Among the ten plays, which one is your favorite?

Elizabeth: That depends on a variety of factors because these weren't just plays, they were

three-year experiences, so each one has something special about it. I really love

these pieces.

SONG Chenqing: Great. Were there incidents and things that you messed up? Would you

mind sharing those stories with us?

Elizabeth: Well, initially, I had to learn a lot of things about how to translate Jingju for performance. I didn't know, for instance, when I did the first translation, that

I needed to approach translating for manban (the “slow beat” meter) differently than translating for yuanban (the “original beat” meter), and differently again than translating for kuaiban (the “fast beat” meter) or erliu (the “two-six beat” meter). I didn't know that to start with. But I learned in the

training program for the first time that, when singing in English, you cannot sustain

one syllable for as long as you would have to in manban without it sounding humorous, since multi-syllabic English words need to have the

syllables connected to have meaning. So I learned that for the very slow banshi (metrical types), it is necessary to have multiple English syllables for one Chinese

syllable. In contrast, for kuaiban and erliu, you can only have one English syllable, just as in Chinese. And then yuanban is in between these two. For yuanban, usually one English syllable per Chinese syllable

works well. But if there's a lot of melisma, i.e., many notes used to sing one syllable,

you may need two or maybe even three syllables instead, just as in manban.

SONG Chenqing: That takes me right to my section of questions regarding translation.

Could you please explain why translation is essential to Jingju?

Elizabeth: Well, that's huge. In my specific context, I've had people ask me why we didn't

just have the students perform in Chinese. And the reason is that our students are

theater students, and they need to be able to use everything they've ever learned

about performance in every performance they give, including Jingju. I don't know if you've paid attention to film actors performing in second languages,

but when you see actors who are superb in their own language giving a performance

in English as a second language, even if they speak English fairly well, they are

usually not nearly as good as in their native language. This is because there are

all sorts of subconscious connections between words, their meanings, and the feelings

that prompt their use. For most people, it takes a long, long time to be able to have

these connections in a second language. So for our students to be able to perform

well, they needed to perform in English. When we had native Mandarin-speaking students,

I invited them to perform in Chinese, but none of them ever chose to do so. Having

them perform in Chinese with the rest of the cast in English would have been another

experience that often happens in modern multicultural theater. But no one ever chose

to create that experience. They were all very much committed to being a part of the

whole, Because the other students were making the transition to performing in English,

they wanted to do the same.

SONG Chenqing: I see. You've used the term performable translation in your writing

and your instruction. What is that?

Elizabeth: I would never advocate having professional Jingju actors perform Jingju in any language other than Chinese. The actual melody and the singing style are completely tied to the Chinese language and related to the tones of Mandarin Chinese, as is the nature of the vowels, and the nature of morphemes. But given that we needed to provide our students with the opportunity not only to learn about Chinese performance culture, but also to utilize their own performance skills, we needed to have a translation. Therefore, it became essential for the English translation to meet Chinese performance requirements as closely as possible. Some of this has to do with translation, and some of this has to do with performance. For instance, song lyrics are written in couplets; each couplet has two lines; and each line is composed of seven characters or ten Chinese characters. The ends of the lines rhyme, and what constitutes a rhyme is determined by the shisanzhe (the Thirteen Rhymes). English is a rhyme-poor language, and Chinese is the reverse. I had to do some redefining of rhyme to make it possible to have that much rhyme in English, and to have the results sound interesting rather than simply repetitive. I therefore defined rhyme as the final vowel, and as having nothing to do with the consonants in the syllable. That leads me to the performance aspect of this same issue. In Chinese syllables, as you know, the only possible final consonants are -n and -ng; otherwise, after an initial consonant or vowel, the final sound of every syllable is composed of one or more vowels. Especially in singing, Madam Shen Xiaomei, my performance teacher, found it hideous when the students were articulating English properly and ending all of their syllables with a variety of crisp consonants. We therefore did two things. For each connection between one syllable and the next, we turned the final consonant of the first syllable into the opening consonant for the next syllable; in this way, as many syllables as possible ended on a vowel. But for the final consonants of many syllables, especially the ones at the ends of sung lines, that just wasn’t possible. Instead, we “softened” those un-connectable final consonants as much as possible, to the point at which the pronunciation of each English syllable and its final consonant was acceptable to Madam Shen’s ears. Given the especially stylized language and vocalization in Jingju singing, it is difficult for most Jingju audience members in China to understand, so subtitles, surtitles, or side-titles are almost always provided. Our “softened” final consonants perhaps increased this difficulty for our English-language Jingju audience members, making the side-titles we provided even more welcome. Interestingly, this intentional change to the standard, clear English pronunciation was somewhat controversial. For instance, Wang Renyuan, a good friend of mine and my fellow student under Professor Wu Junda in Nanjing, felt that this distortion went against the spirit of Jingju, because the spirit of Jingju includes perfect pronunciation. All I could say to him was, well, our artists in residence and our artistic supervisor have the final word; after all, tradition is whatever the artist says it is today, and it could be different tomorrow. Madam Shen Xiaomei was always the arbiter of what sounded like Jingju in performance.

SONG Chenqing: I understand that you, Shen Xiaomei, and your trainees, everybody in

the production worked collaboratively in deciding some of the complex, difficult translations.

But in translation, there's always some trade-off; a balance needs to be established.

There are various considerations, such as sound and meaning, and with meaning, you

have metaphors and the notorious allusions. How did you collectively balance these

factors? Do you have to sacrifice things to maintain sound integrity or make it more

performable?

Elizabeth: Whenever you talk to someone about translating for theater, you always find these

factors. And, of course, you can't have footnotes in performance — everything has

to be understandable. One of the exceptional things about Jingju is that Jingju is an actor's theater form, not just in performance but in the creative process as

well. The creating artists for each one of these English-language productions were

the artist-teachers. When problems arose they could rewrite, rephrase, and in one

instance, even recast. In a few instances, the artist-teachers and I also added things

for clarity. For instance, to explain to the audience Duanwujie (Dragon Boat Festival) and the drinking of the Shaoxing jiu (Shaoxing wine) in White Snake, we added a few lines of conversation for the villagers,

briefly discussing that holiday and that practice, so the plot involving them would

be comprehensible. Otherwise, most of our audience members would not know anything

about them, and would find the action very difficult to understand.

SONG Chenqing: Fantastic! That takes us to the point of the agency or the creativity

of the translator, or in this case, the creativity or the authority of a performing

artist.

Elizabeth: Right. We were working together, the guest artists and I. When we added something,

it would first be written in Chinese by the artist-teachers, and then translated into

English by me. The artist-teachers, who didn't speak English, taught in Chinese with

the help of interpreters, and the students memorized everything first in Chinese,

although they did not speak Chinese. They memorized the Chinese so that they could

imitate their teachers. And after they did that to the teachers’ satisfaction, they

were able to move into English. Moving into English was an uncomfortable, challenging,

and interesting process, even though the majority were native speakers of English.

In the process of memorizing in Chinese, they had internalized important aesthetic

principles. They then had to move everything into English, and we had to find a proper

way to do that. It's actually somewhat easier to make the transition with singing,

since the music provides a precise framework for the translated syllables as well

as rhythm, pitch, and accentuation. It's more challenging to make the transition with

speech. What you should not do, which brings me to the second major thing I did wrong

in early production, is simply take what, in essence, is the melody provided by the

pattern of tones in Mandarin Chinese, and put the English into it, as is done for

singing. For in speech, that process results in an odd-sounding, somewhat culturally

offensive presentation. It is both orientalized and hard to understand. Instead, the

student actors needed to work sentence by sentence, analyzing how the teacher performed

the original Chinese, listening for the tones that are exaggerated for stress, and

those that are underplayed. It is possible to do these same things in English, because

English is also a tonal language, although its tones are connotative rather than denotative.

Once you know which word is the most emphasized, you can exaggerate the stress on

that same word in English, although it probably doesn't fall in the same place in

the sentence because of grammar. The same works for the second most important word,

and so on, so you can work out how you want to place the stresses in terms of the

meaning of the words, following the Jingju principles. Then it is genuinely English speech stylized in the Jingju manner.

SONG Chenqing: So you made your actors go through the pseudo-translation process,

in a sense, because they are moving from Chinese, which they don't speak, into English.

Elizabeth: Exactly. That's what I mean. They had a fair amount of creative agency because they

could undertake their own analysis. Many of these productions were double cast, with

one actor playing the major character while the other played a minor character in

one performance, and vice versa in the next. This allowed everyone to learn more than

if each actor played only one role, and the goal of these training programs and culminating

productions was the learning experience that they provided. For example, in Yutangchun, the Jade Hall of Spring, two actors were cast to play Pishi (Lady Pi). After working with them for several

weeks, Madam Shen Xiaomei decided to help them develop their characters in two very

different directions. One actually became a poladan (shrewish/feisty female role), whereas the other became the sweetest huadan (“flower” young female role), who charmingly set out to poison her rival. They were

very different! But we didn't change the words much at all. Instead, those patterns

of intonation that I'm talking about ended up being quite different for the two characters.

SONG Chenqing: I don't think I've read elsewhere about this process, even from your

writing or other interviews. I think this is going to be something new for the readers.

In an article about you published in 2005, written by one of your students, it is

said you translated ten plays and were continuing to revise them, edit them, and polish

them. I know there's no endpoint to any revision process, but I'm curious about the

revisions you've done since those earlier versions of the translation.

Elizabeth: I'm still working on them because I want to publish an anthology of the plays, but

I am not changing the words. Part of the process is just listening to the videotapes

and ensuring that the text I have on the page is the same as in the actual production,

because things changed so quickly. This is really just cleaning up, bringing the scripts

up to date, and it is well along. Then secondly, I’m putting in stage directions,

and am only about halfway through with that work. I find it rather boring, since it

lacks the challenge of textual translation!

SONG Chenqing: I see. But do you think adding stage directions to your translation

is important?

Elizabeth: It's essential to have basic stage directions, just as novels usually have descriptions; otherwise, it is difficult for readers to imagine what is happening. This process of writing stage directions has taken me a long time because I've changed my mind several times about how extensive the stage directions should be, and the perspective from which they should be written. For instance, you could have something like "enters from stage right, and exits from stage left." Or you could just say, "enters and exits." And I have come around to thinking that it's better for the majority of readers just to say "enters and exits." People who know Jingju will know that the vast majority of stage entrances will be from stage right and the vast majority of exits will be from stage left, because the right side of the stage from the actor’s perspective is called the shangchangmen (stage-entering gate), and the left side the xiachangmen (stage-exit gate). To help myself decide on the amount of detail to provide in stage directions, I tried an experiment. I had the students in my Chinese theater lecture class read one of the plays in translation with very extensive stage directions; I included not only left and right, but also described some of the shenduan (movement sequences) and the clothing. Without exception, including some excellent graduate students, they all felt it was just too much information: "it's impossible to read this,” and “I just get lost in all of this," were representative comments. Although I can imagine an annotated version for a costume designer, or for someone wanting to direct the play, it was clear that for readers in general, putting it all into one text is too much. So I am taking their advice.

SONG Chenqing: This is amazing. I look forward to your anthology. These were my questions

about translation. Now I'm going to take you to the questions about your research.

In one article, you said you studied Jingju from the inside. What makes this approach different from those who did it from the

outside?

Elizabeth: I was very fortunate because I did the field research for my dissertation in 1979-1981,

when recovery from the Cultural Revolution was just beginning. Because the president

of Nanjing University was a ximi (a fan of Jingju), he personally “opened the back door” for me so that I could do my research. Otherwise,

it wouldn't have been possible because foreigners were not allowed in places without

a foreign office. Due to President Kuang’s unique support, I was able to study with

someone like Madam Shen Xiaomei, to have her undivided attention in personal one-on-one

classes several days a week. It would have been very difficult to set up something

like that just a few years later, but it was possible then, with his help. It was

possible for me to spend all my waking hours primarily at the Jiangsu Province Jingju

Company but also at the Jiangsu Province Theater School. President Kuang asked me

to perform in return for his help. So I did, and all those officials came, and there

was all that incredible publicity about it. As a result, major Jingju artists, scholars, and playwrights wanted to meet me, and I had this extraordinary

access. I was taken inside the Jingju world. When plays from Jiangsu Province were requested for performance at various

events, they could select me as Yangguifei (Favorite Imperial Concubine Lady Yang) since I was “on the menu!” I went with the

company to places like army bases, where foreigners were absolutely forbidden to go.

But I was taken there as Wei Lisha, performing Yangguifei. Being “on the inside” was a transformative experience, one that I began trying to

recreate for my own students to the extent possible, beginning just several years

later. With each training program, we immersed the students in Jingju's culture. They had classes every day. They had individual lessons and group classes

from three to eight times a week, and evening group training sessions. The intensity

of it is hard to imagine, because they still had other college classes, as well.

SONG Chenqing: I know some of them studied in the evening. You have seminars for the

grad students in the evening. I think it's connected to your aspiration because you

were put on the inside. I read that you spent your whole career trying to promote

Jingju to the outside world because you were accepted on the inside. And I think in one

interview you said you feel obliged.

Elizabeth: You have to realize that from the Chinese perspective, what I was doing was promoting

Jingju. And two years ago, I got this incredible award for doing that, so I definitely can't

say that I didn't promote Jingju. But, for instance, when you are teaching Chinese linguistics, I will bet that the

largest portion of your teaching time is not about promoting Chinese culture but about

your discipline, about conveying your discipline to your students. That was true for

me, too. My primary intention was not about promoting Chinese culture. But when you

give students that kind of opportunity, working with master artists every day in a

demanding performance culture, I would say the majority of the students develop a

lifelong affection for Chinese performance culture, and for the greater culture that

it comes from and relates to. I think that does happen. And for the students in our

department, there was a cultural rotation. One year it was Chinese theater, the next

Japanese, then Southeast Asia, then a fourth “guest” Asian performance culture. So

in the course of their college careers, they would develop that kind of affection

for three or four performance cultures, and the greater cultures behind them. This

was not our main goal, but it was a marvelous, expected side effect.

SONG Chenqing: I'm going to take you to the questions about the tradition and innovation

in Jingju. So in a couple of your articles, you talked about the concept of "creative authority,"

which links both to tradition and innovation. What do you mean by creative authority?

Elizabeth: It's really very simple: Who gets to decide how something is going to be done? It's

all very well to say that artists are working collaboratively, but at some point,

it has to be decided how it will be done. When we have different options, how are

we going to decide it if there isn’t a consensus? Who gets to decide, who gets to

essentially lead that collaborative process? In realistic Stanislavski-based theater

in the United States, the director has the primary creative authority. The playwright

created the words, so the director and the playwright have to work out their shared

creative authority if it's a new play. But it sure isn't the actors who have overall

creative authority. They certainly are engaged in creativity, but they bring things

in, and the director decides whether s/he likes them or not. As I witnessed from 1978

to the last time I conducted this type of research in 2019, creative authority is

shared to a much greater extent in modern Jingju creative process. Over those forty years, I witnessed the entire creative process

for twenty or more different plays, and the director had nothing like that kind of

creative authority, nor did the playwright. There are also cultural officials with

the company and with the city or the province who have a certain amount of creative

authority. But the actors still have meaningful creative authority despite all these

participants. Before 1950 there were no directors in Jingju, and often there weren’t playwrights; when there was a playwright, the playwright

was almost always working for the lead actor, who certainly had the primary creative

authority. Today there's a lot more give and take. And periodically in the modern

creative process, various of these people will watch a rehearsal, and then come together

with lead actors and other creative personnel, and they'll talk about what's working,

what isn't working, and what needs to be changed. “Let's ask the playwright to do

this and this and this,” is a common outcome. Things happen in those meetings, revealing

a remarkable amount of genuinely shared creative authority. However, the actors don't

have as much creative authority as they used to. And this is problematic since Jingju is only fully taught to actors — they're the only ones who get complete training

in what Jingju is, and how to do it. Even Jingju musicians don't get that much training. The living record, the embodied model of

what Jingju is, lies in the minds and bodies of the actors. So it's quite a loss when their ability

to use all they have to create with isn't better cultivated. It's true that different

actors in different Jingju companies have different amounts of creative authority. For instance, Shang Changrong

certainly has a lot of input into the composition of what he sings. A number of performers

work with the composers and the playwright, and can veto things. It’s hard to imagine

that happening on Broadway! But less well-known actors sometimes have a more difficult

time seizing enough creative authority to be fully present as a performer, and this

is a real problem. In our context at the University of Hawai‘i, from 1984 to 2018

when I was producing these training programs, the vast majority of the creative authority

was with the teaching artists from China. Then a certain amount was with the director

(me), and we tried to give as much as possible to the student actors. For instance,

my initial translation had different choices for most lines, both spoken and sung.

So when the student actors started moving into English, both the teacher and the student

in each case could make decisions about what worked best. The teachers may have found

that some words sounded much better, and the students may have found that some sounds

worked much better. And sometimes, the teacher and the student came back to me and

said, "Nothing here works. Can you come up with something else?"

SONG Chenqing: Since you observed how the creative authority was shared in a performance group, things probably changed in the last 40 years. So many things have changed from then to now. Do you see any changes in the creative authority in today's performers of Jingju?

Elizabeth: I wish you could hear the artists who participated in creating the yangbanxi (the Model Plays) talking about that work as a creative process, as a creative time.

They would become so excited just re-experiencing it! “We could spend days on only

one line of a song, to get it exactly right!” They essentially had unlimited time,

unlimited funding, and unlimited access to personnel in those creative processes.

The yangbanxi were the largest single theatrical experiment I know of in the history of world theatre.

For instance, in creating the music for the singing in the yangbanxi, extraordinary creative things happened including the creation of new banshi, the

combination of banshi that originally were for different roles, and the bringing together

of these two processes. However, in the wake of the Cultural Revolution, using the

new techniques and approaches was not possible; using them was said to have “the flavor

of yangbanxi,” which had to be avoided. And this meant that artists could only use the second-best

or the third-best means for creating a certain effect, or solving a particular aesthetic

problem. This creative straightjacket affected new work for over a decade.

There's one other thing I want to say. Another straitjacket that performers are often

put in is liupai (different schools of performance style). When engaged in creating new work, Madam

Shen Xiaomei complained to me bitterly about the liupai. She loves Master Mei Lanfang; she loves her training; she loves to perform the Mei

style. But in creating new pieces, she doesn’t want to be tied to the Mei style only,

and she was required to be in the Mei style. In essence, liupai used to be a recognition of creativity, but has become a straitjacket that restricts

creativity.

SONG Chenqing: Yes, Jingju is facing challenges but also in today's world, you have multimedia, the connected

world on internet explosion of information available, and YouTube, Bilibili, and all

these websites that host videos not only from actors or seasoned performers but also

from amateurs who want to try it. How do you perceive today's new media world's influence

on Jingju and its introduction to the outside world?

Elizabeth: I don't have any particular wisdom or special viewpoint for this. It would be very

interesting to investigate how such things are handled in professional performance

companies and how they are accessed and considered. I know that the marketing offices

of many companies have added people who focus on social media. It's certainly taken

into consideration, but I don't have any significant information about it. The last

time I observed a rehearsal process was in 2019, and to that point, I never saw social

media come into the creative rehearsal space. It seemed to be limited to the marketing

aspect.

SONG Chenqing: I was thinking about the place where you directed and produced. If

we put you in today's world, after people living in their homes exclusively for two

years, how would you promote your plays, or how would you broaden its audience through

the Internet or remote channels? Back then, you had a live audience, and your students

performed for the live audience. Would you change anything? Would you do it differently,

given today's remote experience? Are there different possibilities?

Elizabeth: If I had tried to carry out a Jingju training program and production during COVID, then promotion or the audience would

not have been the main issues. The real issue would have been the training. It is

very difficult to train in depth on Zoom, so I don't know how effective training could

have been carried out when the teachers and the students could not work together in

person. And that experience for the students is the main goal. The production that's

performed is just the culmination of that extraordinary process, which went on from

mid-August to mid-March, a period that includes the last two or three weeks of performance.

So the performance was only for two or three weeks, but the immersion in Jingju was much longer, lasting over five to seven months. The aim of a theater performance

program is to provide training and experience for the students. So I don’t think I

would try to grind out an English language Jingju production if everybody had to be trained and rehearse on Zoom. Training begins with

jibengong (the core skills), and how do you teach combat and acrobatics on Zoom? I'm active

with a community-based theatre group, and have been conducting Zoom rehearsals for

filmed performances since I retired, so I do have experience with what you can and

cannot do on Zoom.

SONG Chenqing: You've trained students and trained performers. I know you talked about

these must-have components in training. But think about it in a reverse situation.

We want to train cross-cultural or intercultural performers or producers in China.

They are Chinese speakers, young Chinese actors, and actresses who are learning Jingju but also have the aspiration of becoming an intercultural performer, a producer.

What do you think needs to be included in their training?

Elizabeth: Yes, I think the training needs to last a little longer, and various approaches

to individual creation need to be included for reasons I've already discussed.

SONG Chenqing: How about their understanding of Western theater tradition, performance,

and production processes?

Elizabeth: While useful, I think those aspects are less important than the fostering of creativity.

Actors don't need to be historians. Actors don't need to be theater critics. They

need the tools, the techniques, and the powers of creation. If they see Western performances

as part of their theater-going experience, and they get to meet occasionally with

artists from other performance cultures, that may actually be enough. As long as these

young artists are given the opportunity to create, to learn about and explore the

tools and processes of the creation experience, with real agency of creation.

SONG Chenqing: Instead of taking courses, learning theories, studying Shakespeare?

Elizabeth: If you get a chance to be in a Shakespeare play production, you'll read the play,

and I really do think experience is a much better teacher for an actor than classroom

study. But one thing that is lacking for many Jingju actors is script analysis. Script analysis is taught to directors, but actors need

script analysis, too, and they need it for the Jingju plays as well as others. With solid script analysis knowledge and experience, they

will be competent to read and explore almost any script they're handed from anywhere

in the world. So yes, I do think script analysis is important for creative artists.

Producers are another question because they need to know modern systems of production,

and various components that are quite different in different cultures.

SONG Chenqing: Great. I'll pass this message on to those who want to train and produce

intercultural performers and producers. Now my last question. In one of your early

articles, you wrote that Western scholarship could make a substantial positive difference

for Xiqu (Chinese operas) and its performers. Do you think that happened? Has Western scholarship

made a substantial positive difference for Xiqu and its performers?

Elizabeth: That was a long time ago. The article was written at a time when it seemed to be

expected that scholars would save the traditional theater in China. I don't see that

expectation anymore. I think it has failed. Nonetheless, whenever I write anything,

or I deliver a talk in China, I very carefully consider how what I'm going to say

might be beneficial to Xiqu actors, and I try very hard to make sure that there isn't a way it could come back

around and be harmful to them. But honestly, I don't think scholars should have any

real impact on how performance is created or presented, let alone scholars from outside

the culture.

SONG Chenqing: I see your position. I have asked you a lot of questions. Thank you

very much for taking the time to answer these questions. Thank you so much! Your interview

will appear in the first volume of TheaComm.

Date of the Interview:

07/15/2022

Interviewee:

Professor Elizabeth Wichmann-Walczak was the Director of the Asian Theatre Program at the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa from 1985 to 2018. Wichmann-Walczak earned BA degrees in Theatre and Chinese from the University of Iowa, and MA and PhD degrees in Performance and Asian Theatre respectively from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. She acted professionally with the Iowa Repertory Theatre, the Hawai‘i Theatre Festival, and the General Assistance Center of the Pacific; was a board member, director, and actor for Kumu Kahua Theatre during the first 10 years of its existence; taught improvisational and “work-shopped” (now “devised”) theatre at the Hawai‘i State Prison; and taught acting and dance at Windward Community College, before undertaking the field work for her doctoral dissertation on the aural performance of Jingju (Beijing/Peking “opera”) in PR China, 1979-1981. While carrying out that research, Wichmann-Walczak was accepted as the personal student of Master Mei Lanfang’s disciple Madam Shen Xiaomei, and performed the title role in an iconic Mei play in Nanjing & nationally via film and television, becoming the first non-Chinese to perform Jingju in China. Since joining the UHM faculty in 1981, she has worked with Madam Shen to produce an intensive Jingju training program every 4 years, each culminating in public performances of a major play in English which she has translated & directed. To date Wichmann-Walczak and Shen have produced one modern, three “newly-written historical,” and four classical Jingju plays at UHM; at Chinese invitation, three classical plays have undertaken performance tours of PR China. Wichmann-Walczak’s research concerns issues of creative authority in Jingju, especially as they relate to the 1950s national reform of Xiqu (Chinese “opera”) in China, and has received the support of the Fulbright Foundation; previous research support has been provided by the Asian Cultural Council, the U.S. Committee for Scholarly Communication with the People’s Republic of China, the American Council of Learned Societies, and the Freeman Foundation.

Interviewer:

SONG Chenqing

Director; Associate Professor

Translation Research and Instruction Prograam (TRIP); Department of Asian and Asian American STUDIES