Two Late Imperial Chinese Opera Scandals: 1689 and 1874[1]

Judith T. Zeitlin

Résumé:

Deux scandales dans l'opéra chinois de la dynastie Qing: 1689 et 1874.

Cet article analyse deux représentations désastreuses données à Beijing, sous la dynastie Qing, à l'apogée de l'opéra chinois. Par « représentations désastreuses », j'entends des représentations qui provoquent un outrage qui déclenche punition et représailles, avec de considérables répercutions.Le premier cas est célèbre ; il concerne une représentation privée du chef d'æuvre de Hong Sheng, Le Palais de longue vie (1689). Le second, très peu connu, concerne une représentation sur la scène d'un club et implique un puissant général. Ce petit échantillon permet de dégager trois traits récurrents dans les scandales de théâtre sous la dernière dynastie chinoise. Ils sont fortement liés à l'autorité impériale, aux pressions politiques et aux tensions partisanes en coulisse. Ils supposent une lecture symbolique, que ce soit dans l'outrage initial, dans les commentaires contemporains ou dans la reconstruction des historiens par la suite. Enfin, ils montrent que le scandale se développe dans un lieu qui n'est pas totalement ouvert (comme un théâtre commercial) ni totalement fermé (comme la cité interdite) mais qui occupe un espace intermédiaire entre la sphère publique et la sphère privée.

[1] My deep gratitude to Andrea Goldman, Ashton Lazarus, and Paize Keulemans for generously sharing their expertise, to my research assistant Jiayi Chen for her in dispensable help, and to Goldman, Keulemans, Martha Feldman, and Wu Hung for their astute commenst on drafts of this essay. I also thank François Lecercle and Hirotaka Ogura for graciously inviting me to participate in the conference that engendered this volume. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are mine.

Abstract:

This essay examines two disastrous performances that took place in the Qing dynasty capital of Beijing during a heyday of Chinese opera. By “disastrous performance” I mean a theatrical event that gives offense and results in punishment and retaliation, bringing calamity on someone or something, with tangible, measurable repercussions. The first case from 1689 (the early Qing), an ill-fated salon performance of Hong Sheng's masterpiece Palace of Lasting Life, is quite famous. The second from 1874 (the late Qing), a brawl at the Hunan-Hubei Native Place Club theater involving the general Zeng Guoquan, is quite obscure. Though a tiny sample, together they reveal some common patterns in the way theatrical scandals operated in late imperial China. First, both cases have a strong connection to Qing imperial authority and betray political pressures and partisan infighting behind the scenes. Second, both cases entail some sort of allegorical or symbolic reading between the lines, either as part of the initial triggering offense, in the public discourse on the incident, or in enabling later scholars to reconstruct the scandal at all. Finally, both cases show how scandals can develop in “in-between performance spaces” that are neither fully open (like a commercial playhouse) or fully closed (like the Forbidden City), but straddle a borderland between private and public spheres.

Scandal is a rich topic for any historian of Chinese theater, but it has not been much researched in this field, at least frontally. My essay will make a first attempt to scratch the surface. François Lecercle's and Clotilde Thouret's excellent survey of the French term “scandale” in their introduction to a special issue of Fabula on “Théâtre et Scandale” shows the complexity of scandal as a word and a concept and demonstrates how its usages and meanings have changed over time.[2] We would certainly not expect full overlap in Chinese, linguistically, historically, or conceptually, yet we also find quite a few commonalities with the European cases they describe.

[2] François Lecercle et Clotilde Thouret, “Introduction. Une autre histoire de la scene occidentale”, Fabula / Les colloques, Théâtre et scandale, URL: http://www.fabula.org/ colloques/document6293.php. (Consulted April 02, 2020, no pagination) My approaches to scandal in this essay are indebted to their very thorough survey and analysis.

An account of how you say “scandal” in Modern Chinese is revealing and will set the stage, so to speak, for a consideration of operatic scandal. On the poster for the conference on “Théâtre et Scandale” held in Tokyo in October, 2019, the Japanese title simply uses sukyandaru スキャンダル, a transliteration of the occidental word “scandal/e” written in the Katakana syllabary. This is a modern usage of early twentieth-century vintage, but it is only one of several Japanese words past and present to designate this concept, with the other possible choices rendered in Kanji (Chinese characters). Chinese tends not to transliterate western terms directly, so in the later nineteenth century and first part of the twentieth, many new Japanese Kanji coinages that had already translated modern ideas and inventions into Chinese characters were adopted. The most common way to say “scandal” in Mandarin today - chou-wen 醜聞 (shūbun in Japanese pronunciation)—is likely one such compound borrowed from Japanese.[3] According to Ashton Lazarus, “it seems that shūbun's earliest appearance is in an 1874 dictionary called Kõeki jukujiten, where it is defined as an 'indecent/ dirty story.’” The earliest usage of chou-wen I have found appears in the Chinese newspaper Shen Bao (Jan 16, 1913 issue), where it is used interchangeably with the now obsolete term chou-shia 醜史 (disgraceful history) to mean scandal.[4] Hanyu dacidian, the most comprehensive Chinese dictionary, cites only a 1935 usage from an article by the famous writer Lu Xun denouncing the malicious tabloid coverage that drove Shanghai film star Ruan Lingyu to take her own life.[5] The date and context of this later citation anchor the term to a familiar global mass culture where the local media dishes up dirt on celebrities to feed an avid public.

Chou-wen is composed of two Chinese characters. Chou 醜 on its own, as an adjective or noun, means “ugly; physically or morally deformed,” and

[3] Lazarus observes that in contrast to shūbun, “sukyandaru looks to have emerged a bit later in time,” with one dictionary entry citing a text from 1916 (private correspondence, October 10, 2019).

[4] “Esheng nü jie xin chou-shia,” Shen Bao, Jan. 16, 1913, 6. For another instance of chou-shi a [disgraceful history] to mean scandal, see Shen Bao, Mar 11,1911,10.

[5] Hanyu dacidian (Shanghai: Hanyu dacidian chubanshe, 2001), vol. 9, 1435. The brief entry defines chou-wen by expanding each of the characters into a compound: “rumors circulating (chuan-wen) about something disgraceful (chou-shi).” On Lu Xun's article, see Jack W. Chen, “Introduction" to Idle Talk: Gossip and Anecdote in Traditional China, ed. Jack W. Chen and David Schaberg (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2014),1-3.

by extension, something “shameless, disgraceful, scandalous.”[6] Wen 聞 on its own means “to hear; what is heard or known,” and hence, hearsay, rumor, information, reputation, including both oral and written accounts thereof.[7] (For instance, xin-wen 新聞, literally, the “newest information, ” is today a blanket term meaning “news” in the modern media sense, but in earlier times could simply mean the latest hearsay.) As a compound, chou-wen indicates the two conditions that must be satisfied for a scandal to ensue: rumors must be circulating publicly about some incident commonly deemed disgraceful.

Chou also appears in other compounds translatable as scandal, such as chou-hua 醜話 (disgraceful talk) or chou-shi 醜事 (disgraceful matter). But my preliminary survey has found that like chou-wen, none of these compounds has much traction in classical Chinese texts.[8] More productive for tracing earlier concepts and cases of scandal are the cluster of nouns chou modifies related to rumor, hearsay, and gossip, as in wen (see above) or hua 話, which means “talk” or “stories,” as in xian hua 閒話 - idle gossip or chatter. Also relevant is the cluster of ancient meteorological metaphors for rumor and popular opinion like feng 風 (“wind,” “influence”) or feng-yu 風雨 (“storm,” literally “wind and rain”) to convey the fast-moving and forceful nature of public opinion. To “create wind” (sheng feng), for instance, means to “stir up gossip or scandal.” But probably the most common usage is a neutral word, like shi 事: “affair, incident, matter,” or an 案: “case” (in the sense of a legal case, though no legal proceedings are required). Either can be deployed as a single character, or

[6] For the first definition, see Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary (Rev. American ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963), p. 185; for the second, see New Century Chinese English Dictionary (Xin shiji Hanying dacidian), second edition, (Beijing: Waiyu jiaoxue yu yanjiu chubanshe, 2016), 241.

[7] On wen in the context of rumor, gossip, and news, see Paize Keulemans “Tales of an Open World: The Fall of the Ming Dynasty as Dutch Tragedy, Chinese Gossip, and Global News, ”Frontiers of Literary Studies in China 2015, 9 (2): 190-234 and his book Idle Chatter: The Productive Uses of Rumor and Gossip in Seventeenth-Century Chinese Literature (forthcoming). On chou-wen (taken literally as “ugly or dirty hearing”) see his “Jin Ping Mei chongtan: cong liuyan dao chouwen” in Zhongguo dianji yu wenhua guoji xueshu yantao hui (Beijing: Peking University Press, 2011), 395-411.

[8] Hanyu dacidian's examples for chou-shi are all from Qing dynasty vernacular novels; Shen Bao's earliest usage of the term dates to Feb. 25, 1873, 2 (only a year after the newspaper was founded). For the now obsolete usage of chou-hua to mean scandal,see Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage (URL: http://humanum.arts. cuhk.edu.hk/, accessed Apr 10, 2020). It is clear that the terminology for “scandal” was quite fluid in the late Qing and Republican era press.

with a short phrase like a date or a name modifying the “incident” or the “case” to identify it. (The Dreyfus affair or the Dreyfus case would be analogous.) According to Paize Keulemans, who has worked extensively on rumor, gossip, and news in seventeenth-century Chinese literature, “the terms for 'scandal' most often employed seem deliberately unscandalous.”[9]

There are many fertile areas in Chinese opera history to pursue specific scandals, along with the mechanism and outlets for triggering, disseminating, and reacting to them. In this essay, to narrow the field, I explore a particular type of scandal that I call “a disastrous performance,” which I define as a theatrical event that gives offense and results in punishment and retaliation, bringing calamity on someone or something, with tangible, measurable repercussions. The Chinese character huo 禍 (disaster, catastrophe, misfortune) is often applied in such situations. Because my focus is on the theatrical event, I deliberately rule out the abundance of purely literary cases in which the writing or publishing of a play was censored or banned. I also rule out the multitude of general cases in which a blanket prohibition was issued against acting troupes, specific types of operas, or opera performances in toto.[10] Instead, I have chosen two incidents from the Manchu-ruled Qing dynasty (1644-1911)—whose reign encompassed a heyday of Chinese opera—as test cases. (I use opera and theater interchangeably because there was no purely spoken Chinese drama prior to the twentieth century and virtually all plays were built around extensive passages of sung verse.)

These two disastrous performances are spatially connected by being located in the imperial capital of Beijing, but temporally they belong to quite separate historical moments and occurred in very different venues and theatrical contexts. The first case from 1689 (the early Qing) is quite famous; the second from 1874 (the late Qing) is quite obscure. Although a tiny sample, together they reveal some common patterns in the way theatrical scandals operated in late imperial China. First, as a corollary of being set in

[9] Quotation from personal communication, October 21,2019.

[10] Histories and compilations of materials related to the banning of stages, actors, plays, and playwrights provide ample sources. For the late imperial period, see Wang Liqi, Yuan Ming Qing sandai jinhui xiaoshuo xiqu shiliao (Beijing: Zuojia chubanshe, 1958); Ding Shumei, Zhongguo gudai jinhui xiju shilun (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 2008) and Zhongguo gudai jinhui xiju biannian shi (Chongqing: Chongqing daxue chubanshe, 2014).

the capital, both disasters have a strong connection to Qing imperial authority and betray or invoke political pressures and vulnerabilities, political attacks and infighting behind the scenes. Second, both cases entail some sort of allegorical, metaphorical, or symbolic reading between the lines, either as part of the initial triggering offense, in the public discourse on the incident, or in enabling later scholars to reconstruct the scandal at all. In other words, neither of these incidents is straightforward or obvious. This obliqueness tells us something important not only about the operations of Chinese political and literary discourse, but also about the dangerous liabilities of the theatrical event. Finally, both cases show how scandals can develop in “in-between performance spaces” that are neither fully open (like a commercial playhouse) or fully closed (like the Forbidden City), but straddle a borderland between private and public spheres.

CASE I: An ill-fated performance of Palace of Lasting Life, 1689

In 1688, the playwright Hong Sheng (1645-1704) completed his masterpiece Palace of Lasting Life (Changsheng dian) after ten years of work and revision. This historical drama retells the tragic love story of Emperor Minghuang of the Tang dynasty and his most favored consort Lady Yang. During a rebellion in the mid-eighth century, the emperor was forced to acquiesce to his beloved being put to death after his palace troops mutinied on their flight from the capital. The text runs fifty acts long—not an unreasonable length for chuanqi drama, a literary genre that was intended both for reading and for adaptation into operatic performance. The play premiered as a Kunqu opera in Beijing that year to great acclaim and became a big hit. But which troupe of actors performed it? Where precisely was it performed? Who sponsored the performance? How much of the play was performed? (Chuanqi plays were so long they were seldom staged in their entirety).

We know none of the answers to these crucial questions. One reason is that although an extensive commercial printing industry existed, and published plays were numerous and easily available, there was no periodical press carrying reviews, notices, or advertisements, and very little theatrical ephemera survives in print or manuscript before the late nineteenth century. In addition to the low status of professional actors, the second reason is that in the 1680s there were no commercial playhouses in Beijing, the likes of which would not gain a firm foothold in the capital for another two decades

or so.[11] Instead of public theaters, professional acting troupes were engaged to perform in different kind of venues: in private residences, in restaurants and drinking establishments, in guild halls, at temple festivals, even on the street. This diffuse, varied, and vibrant theater scene was highly mobile in part because no built stage sets or stage scenery were required. Although there were some permanent stages, most notably attached to temples for religious and ritual celebrations, most performances spaces were temporary. The most prestigious of them (apart from the imperial court, which constitutes its own eco-system and which I won't treat here) consisted of “salon performances” (tanghui) held in private homes at banquets.[12] This is the kind of venue and occasion at which the disastrous performance of Palace of Lasting Life would have been held. For a salon performance, even a grand one, all that was required was a rug as a designated stage, a seating space for the spectators to watch or listen, and a path for actors to enter and exit some sort of designated offstage space (Fig.1).

We know few concrete details about the scandal that engulfed Hong Sheng and his friends after attending a performance of the play in 1689. The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature provides a brief, bare summary of the facts:

As a result of court factional struggles, accusations that Hong Sheng's Palace of Lasting Life was performed during national mourning for Empress Dong in 1689 led to Hong's imprisonment and expulsion from the Imperial Academy. Among those implicated were the poets Zha Shenxing and Zhao Zhixin.[13]

The men swept up in this scandal were expelled from the Academy or dismissed from office for life, but did not suffer more dire consequences. By Qing imperial standards this was very mild punishment. Other famous

[11] It is possible that commercial theaters were already appearing under the radar. That might explain why it was necessary to issue an edict in 1671 forbidding the construction of playhouses in both the Inner and Outer Cities in perpetuity. See Ding Shumei, Zhongguo gudai jinhui xiju biannian shi, 307-308.

[12] Andrea Goldman argues that we consider court performances as extreme forms of “salon performances.” See her Opera in the City: The Politics ofCulture in Beijing, 1770-1900 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012), 65.

[13] Wai-yee Li, “The Early Qing” in The Cambridge History of China, ed. Kang-i Sun Chang and Stephen Owen (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010), vol. 2, 167 (quotation slightly modified).

Figure 1: Salon performance depicting the 1657 premiere of You Tong's opera Celestial Court Music from his Autobiography in Pictures and Verse (ca. 1694).

cases of literary inquisitions resulted in the executions and wide reprisals against those found guilty of “alleged defamations” against the Manchus, as in the infamous Ming history case of 1661-1663 a few years earlier. Nor did Hong Sheng's play itself suffer. It was never banned, continued to circulate in manuscript, and to be frequently performed. In 1704, the year of the playwright's accidental death by drowning, he had just been guest of honor at a three-day, three-night salon performance of his play in Nanjing hosted by Cao Yin, the rich and powerful Textile Commissioner and a personal friend of the Kangxi Emperor. That same year, Palace of Lasting Life was finally published by the playwright, financed and annotated by his friends. The play went on to be widely reprinted and read over the centuries. Excerpts from the opera continued to be performed, including in the Qing palace, and still

remain in the Kunqu opera repertory today.[14]

We can detect and measure a scandal by the noise it generates. For historians of the past that means written sources. For the disastrous performance of Palace of Lasting Life and its consequences, we have a lot scattered in private writings, but nothing in official sources.[15] The dense 33-page study by Zhang Peiheng (1934-2011), Hong Sheng's mid-twentieth-century biographer, is the most thorough and nuanced. He cites nine major prose accounts in Qing miscellaneous jottings, as well as numerous social and occasional poems by friends or acquaintances of the playwright, including several implicated in the scandal. Zhang maintains that the performance was held at Hong Sheng's own residence in Beijing and staged by one of the city's major opera troupes; that many famous literati were in the audience, but only five men were actually charged and punished; and that the formal charge was brought by an imperial censor named Huang Liuhong.[16]

The further away in time from the event, the more blown up and detailed the reports of the performance grow in the anecdotal literature. It was a gala performance held at a great mansion; fifty officials were dismissed from office. Some scholars ascribe to reports that the Emperor himself read the play and loved it, which spurred the play's initial success on the stage; others claim that he detested it and so was responsible for the playwright's downfall. What's most enigmatic is what caused the Censor to bring charges against the performance if it were not a flamboyant affair. Hong Sheng himself, while very well-connected and enjoying a high reputation as a talented poet and playwright, was politically small potatoes. At the time of the scandal, he had been a student on the rolls of the Imperial Academy for twenty years with no

[14] Near full-length versions of the opera have been mounted in the past decades, probably the first time since that performance in 1704. The Suzhou Kunqu Opera Theatre of Jiangsu Province premiered its “full-length” version (28 out of 50 acts) over three nights (Feb. 17th-19th, 2004) at the Taipei New Theater; the Shanghai Kunqu Opera Troupe premiered their “full-length” version (43 out of 50 acts) over four nights (starting on May 29th, 2007) at the Shanghai Lanxin Grand Opera Theater.

[15] Official sources only corroborate the name of the Empress and the date of her death.

[16] Zhang, Peiheng, “Yan Changsheng dian zhi huo kao” in his Hong Sheng nianpu (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1979), 371-404. Other studies include Chen Wannai, “Changsheng dian chuanqi yanchu zhi huo” in Hong Sheng yanjiju (Taipei: Xuesheng shuju, 1961), 119-134 and Zhu Jinhua, “Changsheng dian yanchu jianshi” in Changsheng dian: yanchuyu yanjiu, ed. Ye Changhai et al. (Shanghai: Shanghai chubanshe,2009), 326-347.

official position in sight. It is this disconnect between the charge, the culprit, and the punishment, I believe, that was most scandalous and that helped trigger all the rumors and gossip about the incident, especially since the punishment meted out was not severe enough to silence entirely the wagging tongues. Much of what we know about early performances of the play comes from Hong Sheng's own prefaces to his play, which understandably make no allusion to the calamity that the 1689 performance provoked.

The assumption shared by every writer on the case, then as now, is that the charge of violating the mourning period was only a pretext, and their general tone is one of sympathy toward the playwright. Although it is possible that either Hong Sheng or friends of his who attended the performance had personally offended someone (such as the Censor who brought the charges), the general view is that the playwright was only a scapegoat. But by whom and why was he scapegoated? By someone, perhaps an uninvited guest, envious of Hong Sheng's success as a dramatist? By someone simply bearing a personal grudge against him or other attendees? Or by high officials at court aiming to strike at more powerful political enemies in party infighting (the current consensus)? An unusually straightforward poem written to Hong Sheng in 1691 by a close friend implies all of these reasons:

Your forthright nature put you at odds with the times,

Your lofty talent incited the jealousy of the crowd.

Who would expect a political clique to grow angry?

It was nothing more than actors in a play.[17]

Some scholars like Zhang Peiheng believe that there was also something politically seditious in the content of the play that aroused the Kangxi Emperor's hostility toward it, but this point is far from proven. The one potential charge that Hong Sheng himself is anxious to forestall and refute about the play is that of obscenity (a frequent reason for banning plays in edicts).Hong emphasizes in his prefaces that he has purged his play of the kinds of salacious details found in earlier dramatic treatments of the story.[18]

[17] Wang Zehong (1626-1708), “Upon Seeing Off Hong Sheng on his Return Home to Hangzhou” (“Song Hong Fangsi gui Wulin”) in his Heling shangren shiji, juan 12. In Qingdai shiwen ji huibian, vol. 101, 573 (Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2010), 573.

[18] Hong Sheng, “Zixu” and “Liyan” in Changsheng dian jianzhu, ed. Takemura Noriyuki and Kang Baocheng (Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou guji, 1999), 1-6.

Suppose, then, that we concede that the surviving archive of writings related to the case is disappointing or at least unenlightening. One document in particular stands out because it addresses not just this particular scandal but the nature of scandal itself. This 1695 preface to the play by the prominent Qing dynasty scholar Mao Qiling (1623-1716) is especially valuable because it was written upon request during a personal visit from the playwright, only six or seven years after the events. The preamble lays out Mao's commiseration with the author's misfortune in general terms:

The talented man of letters, unable to realize his ambitions because of the times, often resorts to songs and arias as a form of solace and release for the oppression and obstacles he faces. Originally, the writer was doing nothing more than expressing this predicament; he never bore a grudge against a particular person. But people jealous of his talent, apprehending the feelings of injustice in the work, will actually turn the writer's words against him to add to the oppression and obstacles he encounters. Yet, it is often on the basis of this very thing that his work circulates and lasts (italics mine). [19]

The opening lines are boilerplate in terms of traditional Chinese ideas of authorship and the defense of the high-minded gentleman misunderstood and persecuted by petty men. What is novel and significant for us is Mao's argument that using a writer's work to harm him often rebounds to his ultimate advantage. Then follows an account of the circumstances that led to the play's debacle, spread by “those who talk of the 'latest news' (xin-wen) in the capital.” Without naming names, Mao deploys coded historical allusions to explain the underlying motives, concealing and revealing in equal measure: “Someone said: Su Shunqin was blameless; in directing animosity toward Shunqin, the intent was not Shunqin.” [20] The reference is to the case of a Song dynasty poet and official from the eleventh century, who was brought down for a minor offense at a banquet as a result of partisan infighting by his political enemies to strike at more powerful higher-ups.

The preface concludes by circling back to the general theme of scandal: “It's simply that society loves 'the latest news' (xin-wen). It was on the basis

[19] Mao Qiling, “Changsheng dian yuanben xu” in Changsheng dian jianzhu, 366-367.

[20] Mao uses Su Shunqin's cognomens Canglang and Zimei here. The same allusion was also deployed by Zha Zhenxing, one of the poets punished in the scandal, in complaining about “busybodies who stirred up trouble, and bystanders who added blame.” Cited in Zhang Peiheng, “Yan Changsheng dian zhi huo kao,” 379.

of his play that this 'affair' (shi) ensued, but then it was on the basis of this 'affair' that everyone sought out his play.” I think we are justified here in considering both “the latest news” and the “affair” as related to what he criticizes as society's taste for gossip and scandal. Mao makes a familiar sounding point - familiar to us in our media saturated age - that scandal is actually good because it stirs up public interest and attention, and can lead to the widespread, lasting repute of a work.[21] (Mao uses another historical allusion to compare the fate of Hong Sheng's play to an “elephant whose body is burned for its precious tusks” but whose tusks are never consumed by the flames.) [22] The continued fame of the work thus produces a feedback loop in which people keep becoming newly interested in the old scandal, which provides it a kind of “lasting life” along with the play that provoked it. This certainly proved true in the case of Hong Sheng's masterpiece.

CASE II: A brawl at the Huguang Native Place Club, 1874[23]

We must jump almost two hundred years forward to our second case. This is a much juicier incident, but it generates much less noise in terms of measurable public reaction. To borrow Lecercle's and Thouret's distinctions, it isn't clear that there was much “social amplification” that “enlarged it to the public sphere” at the time-in 1874 or even at the tail end of its consequences in 1892.[24] Thus although the incident was certainly scandalous, it barely qualifies as a scandal. Nonetheless this case showcases the role that theatrical architecture can play in shaping a scandal in its entirety, from triggering offense, to retaliation, to dissemination and interpretation. The case also highlights how the close connection between Chinese opera performance and

[21] For echoes of this view in modern scholarship, see Zhu Jinhua, “Changsheng dian yanchu jianzhi,” 327-328.

[22] See The Zuo Tradition, ed. Stephen W. Durrant et al. (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2016),1126-1127.

[23] I thank Andrea Goldman for bringing this incident and the sources to my attention. Much of my discussion of Beijing theaters in this section is based on her Opera and the City, chapter 2.

[24] Lecercle and Thouret (“Introduction”) distinguish between the scandalous (the offense) and the scandal (the indignation and/or punishment). They maintain that a theatrical scandal in the modern sense of the word requires 1) a triggering factor (a performance that shocks or offends); 2) a negative reaction by some spectators (real or imagined); 3) a reaction to the reaction that enlarges it and brings it to the public space: “There is no scandal without social amplification.”

ritual occasion, on the one hand, and the habit of allegorical reading, on the other, greatly increase the disastrous possibilities of a theatrical event.

As far as I know, we have only two sources for this case: a novel entitled An Unofficial History ofthe Opera World (Liyuan waishi, 1930), and a memoir called Sketches from a Lifetime of Watching Opera (Guanju shenghuo sumiao, serialized 1933-1934). Both were written decades after the alleged events by Chen Moxiang (1884-1943), a prolific playwright, theorist, and historian of Peking opera as well as an accomplished amateur performer of female Peking opera roles.[25] In the framing of the story, there are some differences between the novel and the memoir, but they don't so much contradict as repeat and amplify each other. The memoir recounts some events that occurred before the author's birth, while the novel involves many real people, and verifiable places, dates, and events. I believe it's fair to consider both of these sources as semi-fictionalized histories.

In his memoir, Chen, writing from his own point of view as a child, recalls having heard the story from a friend of his father's when he was eight years old. The occasion for the story was the completion of the renovations of the Huguang Native Place Club (for Hubei and Hunan provinces) in 1892, to explain how it happened that the renovations were required in the first place.[26] (Chen's family was from Hubei, and his father was a high Qing official residing in Beijing; his father's friend was one of the main Qing officials who sponsored the renovations.)

The key to the incident is the theatrical venue itself: the Huguang Native Place Club, whose reconfigured theater is still in use today. By the 1870s, Beijing had had a vigorous commercial playhouse district for more

[25] Novel: Pan Jingfu and Chen Moxiang, Liyuan waishi (Beijing: Zhongguo xiju chubanshe, 2015), chapter 29, 179-183. The first 12 chapters of the novel were published under pseudonyms (Beijing: Jinghua yishuju, 1925). The completed novel in 30 chapters appeared under the authors' real names (Tianjin: Baicheng shuju, 1930), two years after Pan's death; since the incident appears in the penultimate chapter, Chen was probably the sole author. Memoir: Chen Moxiang, Guanju shenghuo sumiao, first installment, 192-199. Originally published in Juxue yuekan (Theater Monthly) (March 1933, vol. 2, issue 3).

[26] On native place clubs in Beijing, see Richard Belsky, Localities At the Center: Native Place, Space, and Power in Late Imperial Beijing. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Asia Center, 2005). For historical confirmation of 1892 for the renovation's completion, see Beiping Huguang huiguan zhilüe in Hunan Huiguan shiliao jiuzong, ed. Yuan Dexuan et al. (Changsha: Yuelu shushe, 2012), 250; 348-350.

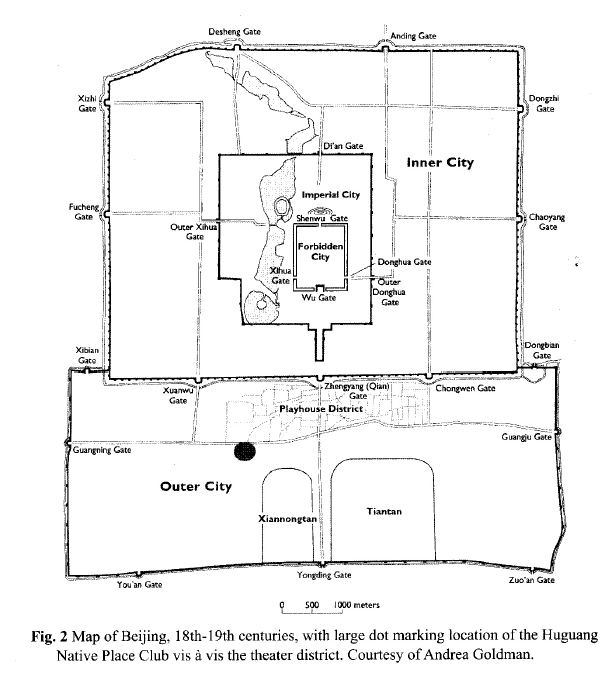

than a century, which was restricted to the Outer City just south of the Inner City gates. Playhouses were more heavily regulated in Beijing than in other Chinese cities because it was the capital and the seat of imperial power. Native place clubs were also located in the Outer City but a little further to the west (Fig. 2). As the social, religious, and entertainment hubs for the many officials and businessmen from the provinces sojourning in the capital or just visiting, the clubs typically included both lodgings and a theater on the premises.

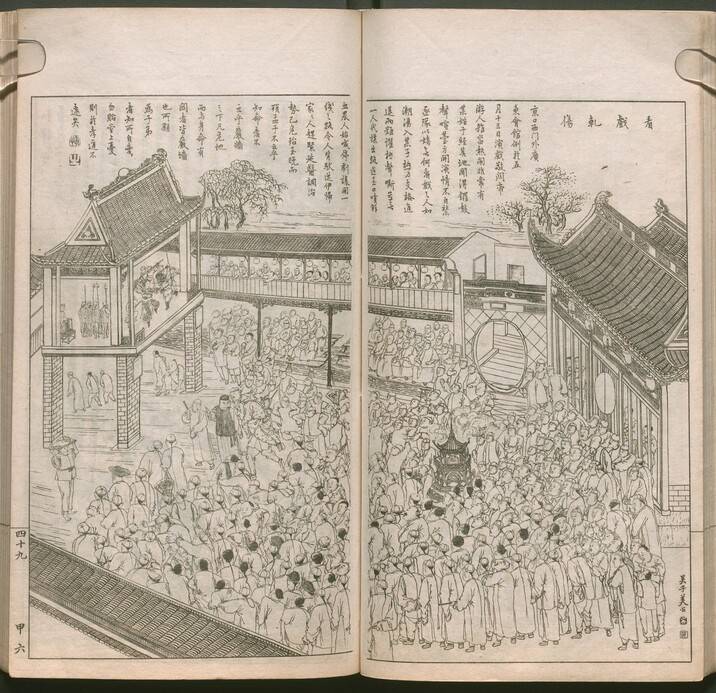

Unlike regular playhouses, the native place club theaters were not commercial venues where you could just buy a ticket to see a show. They more resembled “salon performances” hosted by the members collectively or individually, and you usually needed some sort of connection or invitation to attend. On the other hand, they were much less exclusive than the salons that held performances in private homes, also still common at the time. We may think of the native place clubs—of which there were many in late imperial Beijing as well as in other cities across the empire—as intermediate spaces lying somewhere on the spectrum between the public and the private spheres. And significantly for this incident, unlike the commercial playhouses in Beijing at the time, which not only forbade women on the stage but also in the audience, the attendance laws were laxly enforced for native place club theaters. Female relatives of members and their friends were naturally keen spectators of the opera performances held there, but would be seated up in the balcony to preserve the separation of the sexes (Fig.3).

Figure 3: Caption reads: “Trampled to Death at the Opera.” Illustration by Wu Youru shows the Canton Native Place Club Theater in Jinjiang City, Jiangsu during the birthday celebration of Guangdi, God of War. Dianshizhai Illustrated News, May 13, 188. Source: Dianshizhai huabao. Shanghai: Shanghai huabao chubanshe, 2001, vol. 1, 50.

(Below is a scanned version of the same book from another source. - Editors of TheaComm)

The particular occasion that provoked the incident was a grand one. A famous military commander Zeng Guoquan (1824-1890), whose nickname was “The Ninth Marshal,” was in the capital for an audience in the Forbidden City.[27] Since he was from Hunan, his fellow provincials feted him by inviting him to a series of Peking opera plays at the Huguang Native Place Club. (By this time, Chinese opera had become a repertory theater where a program consisted of a mixed bill of excerpts adapted from famous operas rather than an opera performed in its entirety, and Peking opera had eclipsed Kunqu opera in popularity.)

Imagine the scene. The place is jammed with spectators, rather than limited to a select few. As is typical for salon type performances, the Ninth Marshal, as guest of honor, is presented with a “menu of opera excerpts” in the troupe's repertoire and asked to choose a play to be performed. Unfortunately, the Marshal is no opera connoisseur. He quickly peruses the longlist of titles and randomly selects one that sounds auspicious for the occasion and appropriate to his military accomplishments: Pacifying the Realm (Ding Zhongyuan).[28] Once the opera has begun, the Marshal quickly realizes he's made a terrible mistake-his choice turns out to be an alternative title for a history play called General Sima Threatens the Imperial Court (Sima shi bigong).[29]

Horrified that by choosing this opera he has just laid himself open to the

[27] Zeng Guoquan's annalistic biography (nianpu) confirms that he made two visits to Beijing from Hunan in 1874 (Tongzhi 13). See Mei Yingjie et al., “Zeng Guoquan nianpu” in Xiang jun renwu nianpu (Changsha: Yuelu shushe, 1987), vol. 1,467-538; on 496. The novel (182) says Zeng had just been appointed Governor of Shaanxi, but according to the nianpu (497), he did not receive that appointment until 1875 (Guangxu 1), two months after the Tongzhi Emperor's death in 1874. Zeng's older brother Zeng Guofan, who had died earlier that year, was a towering late Qing military leader and statesman, and the entire Zeng family was extraordinarily powerful.

[28] The title is particularly apt because as a commander of Hunan Army forces during the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864), Zeng played an instrumental role in subduing the rebels and thus “pacifying the realm” for the Qing government during the blood siege of Nanjing when his forces recaptured the city in 1864. But Zeng earned notoriety for allowing his troops to run amok in the city. The appalling massacre of the inhabitants and scale of the destruction were considered excessive even for those violent times. See Chuck Wooldridge, City of Vîrtues : Nanjing in an Age of Utopian Visions (University of Washington Press, 2015), 117.

[29] Peking opera excerpts often circulated under more than one title; changing the title was a common practice for acting troupes as a way of avoiding censorship and enticing audiences with what seemed like a new play.

charge of harboring seditious intentions, he stands up and heads for the exit to make a show of political loyalty. As he is walking out of the theater courtyard, his face is suddenly drenched with some sort of putrid liquid. He looks up and sees an official's wife in the balcony holding up a little boy who is pissing off the side. Even more embarrassed, the Marshal begins cursing at the woman, who curses him back (much embellished in the novel). Other spectators join in, and soon there is total mayhem on the theater grounds. Someone hurls a large tobacco or opium pipe from the balcony, which hits the Marshal in a very sensitive place. His aides, outraged, leap to his defense, crying: “How dare you strike His Excellency's testicles?” The Club officials apologize profusely, the Marshal leaves in a fury, and peace is finally restored. But the next morning, ostensibly on the pretext of violating the ban on women in theaters, the Marshal sends his guards with orders to demolish the theater.

The guards manage to pull down the buildings on three sides,[30] leaving only the principal building with the stage before the Club officials are able to persuade them to stop (Fig. 4). A main difference in the telling between the

Figure 4: The Shanxi Native Place Club theater in Suzhou, now part of the China Kunqu Museum, approximating the Huguang Native Place Club Theater layout in 1874. Photo by Jiayi Chen.

(Below is a photo of the same place from another source. - Editors of TheaComm)

[30] The novel (Liyuan waishi, 183) says there were buildings on three sides; the memoir (Guanju shenghuo, 194) says there were only two.

novel and the memoir is that the novel adds a twist to explain why the Marshal halted his vendetta in time. The wily officer in charge of the Club sends him a piece of paper with only six words written on it: "General Sima Threatens the Imperial Court," thus implicitly threatening to denounce him to the authorities or his political enemies and create a real scandal unless he desists. (The Ninth Marshal was well-known to be embroiled in major partisan infighting and instantly got the message.)

The effectiveness of this threat depends on the mutual recognition that there is no "symbolic mediation" separating the Ninth Marshal and his operatic avatar General Sima. It confirms Lecercle's and Thouret's insight that "the abolition of the distance between the real and representation, between reality and the theater" is a frequent ingredient in a "scandal cocktail."[31] In this case, however, the potential scandal is effectively suppressed from being publicly amplified and is averted. But the novel adds one final flourish. News (xin-wen) of the Marshal's having demolished three-quarters of the Huguang Native Place Club theater circulated all over town, but now it is the city folk's turn to offer an allegorical interpretation. They treat the demolition as a political omen: "Tearing down a theater not far from the Emperor's feet for no reason is inauspicious (my itals)." Here lack of knowledge due to the suppression of the real reasons behind the destruction is what enables the allegorical reading. This interpretation proved prophetic, concludes the novel (with the benefit of hindsight), since the reigning Tongzhi Emperor had died that very year without providing an heir.

What is most striking in this case is that the direct retaliation and punishment for the disastrous performance is not meted out against persons—the officials for hosting the event, the actors for having the play in their repertoire, or the badly-behaved spectators—but against the theater buildings themselves: only the main stage, the culprit "that caused the disaster," as the novel puts it, is left standing.[32] The story gleefully exposes why the Qing state was so anxious to police not only gender distinctions but status distinctions in regulating opera audiences in the capital. Both the novel and the memoir delight in presenting an unruly female attack on a male bastion of state authority, both military and civil, first through the pollution of bodily fluids

[31] Lecercle and Thouret, "Introduction."

[32] Liyuan waishi, 183.

from the mother's child, then through a barrage of her verbal obscenities, and finally through the flying missile that strikes his groin and “emasculates” him.

To conclude, I want to raise the issue of a historical scandal's “shelf-life” and broach how the changing circumstances behind its reconstruction influence its interpretation and reception. By the time Chen Moxiang'sc novel and memoir recounting the scandalous affair of the Huguang Nativec Place Club was published in the early 1930s, not only were all the majorc articipants long dead, but the Qing dynasty had been toppled and with it the centire dynastic system. Beijing was no longer the capital and even the city’s name had been changed.[33] So the affair could no longer pack a scandalous punch. Instead it only elicited comic nostalgia, enhanced by Chen's exuberant narration.

To return to our first case, although it took place so much earlier than our second, for Hong Sheng's biographer Zhang Peiheng, writing in the wake of the Anti-Rightist campaign in the People's Republic of China, the machinations behind the scene that caused the Palace of Lasting Life scandal must have seemed depressingly familiar. It is no surprise that he devoted so much effort to uncovering party infighting and assumed that the content of the play must have offended the Emperor—the leadership at the highest level. Although Zhang completed his manuscript in 1962, he was only able to publish it in 1979 after the Cultural Revolution had ended, when normal academic life had resumed and when traditional operas like Palace of Lasting Life could once again return to the stage. But that is the occasion for another story.

List of Figures:

Figure 1: Salon performance depicting the 1657 premiere of You Tong's opera Celestial Court Music from his Autobiography in Pictures and Verse (ca. 1694). Source: Performing Images: Opera in Chinese Visual Culture, ed. Judith T. Zeitlin and Yuhang Li. Chicago: Smart Museum of Art,2014,141-142.

Figure 2: Map of Beijing, 18th-19th centuries, with large dot marking location of the Huguang

[33] The city's name was changed from Beijing (Northern Capital) to Beiping (Northern Peace) in 1928.

Native Place Club vis à vis the theater district. Courtesy of Andrea Goldman.

Figure 3: Caption reads: “Trampled to Death at the Opera.” Illustration by Wu Youru shows the Canton Native Place Club Theater in Jinjiang City, Jiangsu during the birthday celebration of Guangdi, God of War. Dianshizhai Illustrated News, May 13,1884. Source: Dianshizhai huabao. Shanghai: Shanghai huabao chubanshe, 2001, vol. 1, 50.

Figure 4: The Shanxi Native Place Club theater in Suzhou, now part of the China Kunqu Museum, approximating the Huguang Native Place Club Theater layout in 1874. Photo by Jiayi Chen, with permission.

This article was published in English in 2021.

Zeitlin, Judith. “Two Late Imperial Chinese Opera Scandals: 1689 & 1874." Scandales de théâtre en orient et occident de la première modernité à nos jours. edited by François Lecercle and Hirotoka Ogawa. Tokyo: Sophia University Press, 2021, pp. 163-182.